Jennifer Grey delivered a scene-stealing performance in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” (1986) as the ignored younger sister Jeanie, trapped upstairs when her school’s principal breaks into their house looking for her brother. The next year, as Baby in “Dirty Dancing,” she became a star and the subject of one of the most well-known lines in movie history: “Nobody puts Baby in a corner. C’mon.”

After that film’s surprising success, Grey should’ve had the time of her life. But right before the premiere, she was a passenger in a car collision that killed two people and severely injured her boyfriend who was driving, Matthew Broderick. Then a few years later, a nose job left her unrecognizable to even her closest friends and family, thus ending her career just as it was gaining steam.

“It was like I had a disfiguring accident where I became more conventionally pretty. But it destroyed what I built and what I believed in,” Grey tells Press Play.

She adds, “It ruined my life as I knew it, and that was actually one of the greatest things that ever happened to me.”

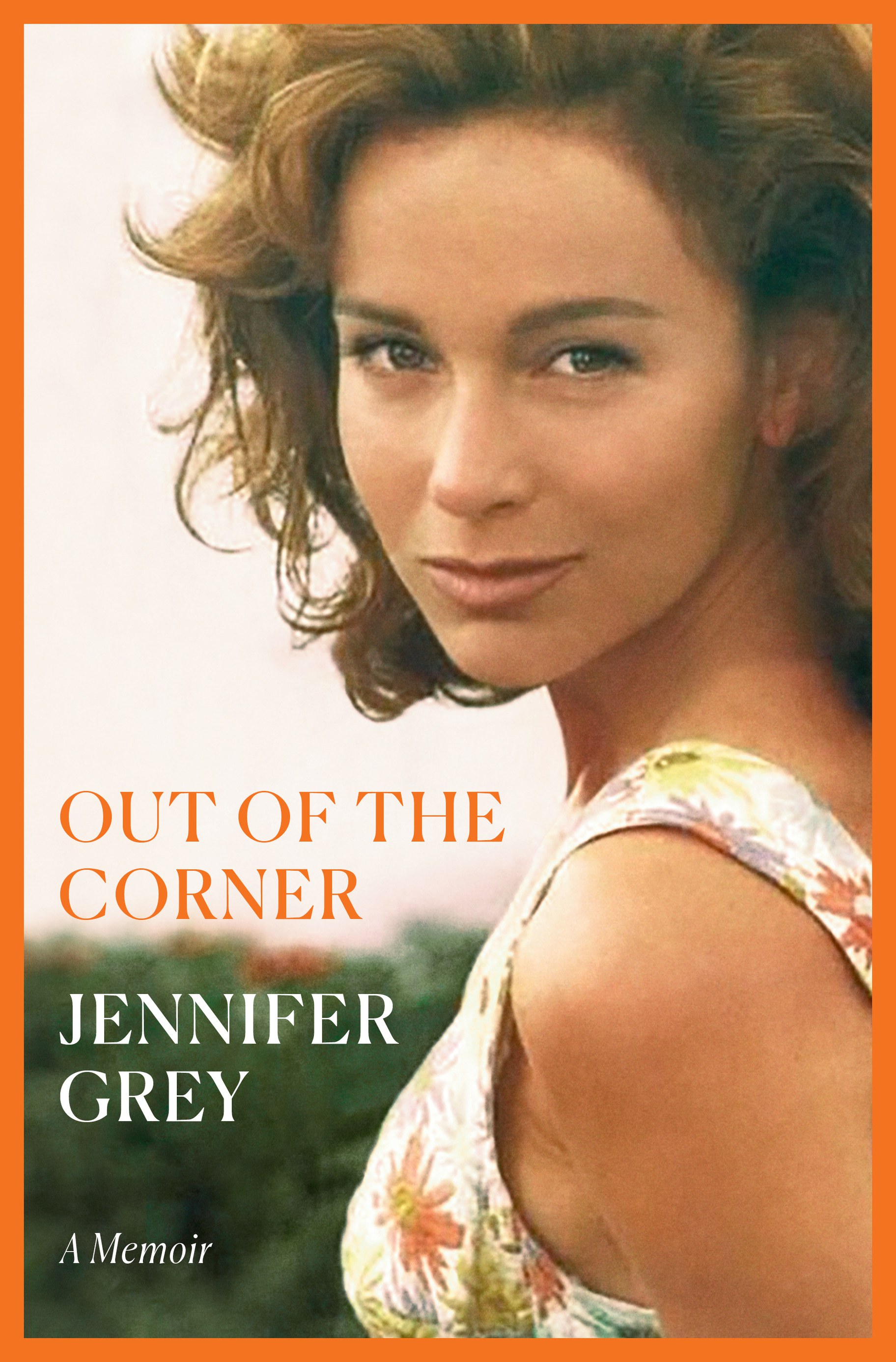

Now Grey is out with new memoir called “Out of the Corner.”

Jennifer Grey’s new memoir is called “Out of the Corner.” Courtesy of Ballantine Books.

Excerpt from Out of the Corner by Jennifer Grey

1

Life Is a Cabaret

When you’re born into a family you really have nothing to compare it to. There is no opinion, no preference, no judgment, no awareness of anything even existing outside of your reality. There is just the instantaneous and immutable devotion to these beings, your source for everything you need to survive, and an acute myopia rendering whatever is beyond this complete triangle, if indeed there exists anything at all, blurry and moot. Which is fine because, if you’re lucky, everything you need is right here. And it was for me.

I made an early entrance, a month before I was due, while my dad, the actor Joel Grey, was out of town, doing his nightclub act in the Catskills. My mother’s water broke while she was at a party in West Hollywood, and two of her actor pals drove her downtown to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, where I was delivered via an emergency C-section.

When the doctor called my dad to tell him of my surprise arrival, it was six in the morning on the East Coast. The operator said, “I’ve got a person-to-person call for Mr. Joel Grey from Dr. Maury Lazarus,” and my dad, who picked up the phone in his sleep, promptly hung up. The doctor called back and yelled over the operator, “Tell him his daughter is born so he better accept the call!”

My dad had been acting professionally since he was a little kid, but in his late twenties, around the time I was a year old, he was hitting his stride, and his career was cookin’. He landed his first Broadway show, replacing the lead in the Neil Simon comedy Come Blow Your Horn. It was Simon’s first play, and a huge hit. So our family picked up and moved from the modest cottage in the Hollywood Hills where they’d set up house, to two floors of a brownstone on East 30th Street in New York City.

My mom, Jo Wilder, was a performer, too. Every baby’s their mother’s biggest fan, and I was no different, but my mom actually looked like a movie star. Visual timelines of my parents’ careers lined the walls of wherever we were living. Framed, black-and-white production stills of my mom as Peter Pan, with a pixie cut, flying in midair in green tights. As Gypsy Rose Lee in Gypsy, a femme fatale mid-striptease, her spaghetti straps suggestively hanging off her bare shoulders. As Polly Peachum, donning a man’s bowler in Threepenny Opera. With her cropped bangs, heavy brows, and winged eyeliner, she looked more than a little like Audrey Hepburn. Everything about her in these photographs exuded theatricality, her mouth impossibly wide, in full song. She looked like she was born to be on the stage.

I loved it when my mom would sing me the lullaby “Little Lamb” from Gypsy and tell me about how the real-life lamb would sometimes pee while she held it in her lap on stage, and she’d have to pretend it hadn’t. She sang around the house all the time.

She wasn’t a kid when she had me. She was closer to thirty than twenty, and had been at it, knocking around the business for some time, ready for her ship to come in when she met my dad. He was very keen to get married and start their family right away. She didn’t know what the hurry was, but got swept up in his vision for them.

My parents had lost a baby before me, and my mother had struggled to carry me to term. So when I was four and a half, my parents decided to adopt a baby boy. The three of us flew out to Los Angeles, and we left a few days later a family of four, bringing back with us to New York my newborn brother, James Rico. (Not the most Jewish of middle names, but my parents were fans of the painter Rico Lebrun.) Jimmy was one of those gorgeous babies right out of the gate. Blond, big blue eyes, white-white skin, and in addition to our genetic differences, my brother felt energetically almost like a different species from the three of us, but a breathtakingly beautiful one. He looked like an angel.

My parents referred to our gang as the four J’s: Jo, Joel, Jenny, and Jimmy. Being a close family was of paramount importance to them. There was a lot of love there.

My dad and I were tight. When I was little, I would wear his old crew neck undershirts, worn so thin and ridiculously soft the cotton was almost diaphanous. I remember the perfect stack of his white tees, folded with origami-like precision in his antique armoire, weighted down by a heavy round bar of Roger & Gallet soap, wrapped in its signature crinkled silk paper and seal. Opening the cabinet door filled my nose with the most intoxicating combination of lemon, bergamot, rosemary, orange, neroli, rose, and carnation. I’d sleep in his T-shirts as nighties, comforted by that warm scent, probably the closest approximation to what happens when a baby smells her mother’s breast milk. Does that sound weird? Well, so be it. I was never breastfed, but I felt utterly peaceful and held, enveloped in that sensorial refuge.

My dad was the one I woke up in the middle of the night when I was scared that I was about to be sick. He’d immediately get up and follow me silently into the bathroom to keep me company. He’d place the bath mat on the cold tile floor in front of the toilet for me to bravely kneel on as he lifted the seat. We’d sit in silence. He’d softly repeat, his eyes at half-mast, “You’re gonna feel much better once you get this out.” I hated that feeling so much, terrified of what was coming, my tiny body wracked with overpowering waves of spasms and retching. But with him at my side, his quiet presence, the cool washcloth he placed on my forehead or the nape of my neck, I could stay the course through this gastrointestinal storm. Afterward he’d have me splash my face with cool water, brush my teeth, and he’d tuck me back into bed.

I felt special, if not guilty, that I got what seemed to me the best of my dad. But within the family, my mother, brother, and I were a team, the spokes that sprung from the hub of the wheel that was my dad and his career. He was a rising star on Broadway, and when he was doing a show, we ate dinner at 5:30. Because theater folk are night owls, Jimmy and I were on our own on weekend mornings, expected to “quietly amuse ourselves,” watching cartoons and helping ourselves to bowls of cereal, so our parents could sleep in until eleven.

For me, there was no place cooler on earth than hanging out backstage with my dad on Saturday matinees, following his every move as his diminutive shadow. Watching him apply his Kabuki-esque makeup for the role he originated as the Master of Ceremonies in the stage version of Cabaret filled me with this deep knowing of how lucky I was to be right where I was. The years 1966 to 1968—when I was six till I was eight—were my Cabaret years. My dad performed eight shows a week, and though he wasn’t around most evenings, I was thrilled when I got him all to myself on a Saturday afternoon. I would sit quietly in his dressing room, fully cognizant of the special honor and privilege it was to bear witness to this sacred preshow ritual and transformation.

It felt like a delicious mix of fizzy and calm, but mostly of reverence. The makeup mirror was an altar, my dad’s face, like the center of a sunflower, both making the art and being the art simultaneously. One step removed, I’d watch every brushstroke in rapt attention, gazing at my father’s reflection from behind him, the image framed by the tiny globes of vanity mirror lights. I surveyed the scene like a detective, making mental notes of the accoutrements in evidence. The cough drops and good luck totems, photos of my mother, brother, father, and me in Lucite DAX frames. Taped to the outer edges of the mirror were opening-night telegrams from friends, along with pencil and crayon stick figure drawings my brother and I regularly made for him to wish him luck.

From inside his dressing room, I could feel the kinetic energy of the company percolating just outside his open door, the raucous laughing, singing, vocal warm-ups with booming scales echoing through the stairwell. Flirtatiousness was the native tongue of this sexy company, his spirited, fun-filled “work family” spontaneously popping their heads in, paying respect. My dad only momentarily averted his gaze from his painstaking task to proudly announce my presence through the mirrored reflection.

The only person other than me granted an all-access pass into my dad’s sanctuary was his dresser. The relationship between actor and dresser is an intimate one. In addition to dressing the actor from head to toe like a small child, the dresser is responsible for maintaining, mending, and laundering the costumes, as well as coordinating postshow visitors. Their job is to facilitate and smooth over everything the artist shouldn’t have to be bothered with, intuiting every mood and unspoken request, whether it be cheerleader or dead silence. The really good ones anticipate every need before the performer is even aware of it.

Quiet as an apparition, their complexion pale and waxy from lack of fresh air and sunlight, a dresser is like a ghost who has no needs other than to serve. A special breed, usually attired in all black to be invisible when moving in the shadows of backstage, they sport sensible shoes and an apron—the equivalent of a tool belt for costumes, stocked with solutions for any potential emergency: tape, tissues, safety pins, miniature flashlight for quick changes in the pitch dark. Dressers are Broadway’s selfless, unsung heroes.

Excerpted from Out of the Corner by Jennifer Grey. Copyright © 2022 by Jennifer Grey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.