Anita Hill was a 35-year-old law professor when she told Congress that President George H.W. Bush’s Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her. It was when she worked for him at the Department of Education and then at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the early 1980s. Her testimony was 30 years ago, on October 11, 1991. By now the details are well known: There were pornographic images, the coke can incident, and the pressure to date him. And she quit.

A decade later, when she testified about those incidents before the Senate Judiciary Committee and on live television, her life changed. She went from being a relatively unknown law professor at the University of Oklahoma to a high-profile and outspoken advocate for victims of workplace harassment and sexual assault.

She still teaches law — now at Brandeis University just outside Boston.

Anita Hill has written a new book about what was — and wasn’t — learned in the last 30 years. It’s called “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence.”

Hill tells KCRW that she’s had the time to process the gravity of her experiences, though she’s moved on.

“I've grown. I’m much more aware now of what was actually happening to me. And my analysis would be that that sense of helplessness that I felt was exactly what other people feel when they're sexually harassed, or they believe that they are being extorted for the sex that they do not want to participate in,” she explains. “It reminds me that that is exactly, in many cases, what the harasser wants. He wants that sense of helplessness on the part of an individual whose job is vulnerable, over whom he has control.”

Leaving D.C. but still carrying the mental toll of trauma

Hill grew up in rural Oklahoma on a family farm, and was the youngest of 12 siblings. She says she learned how to be strong thanks to her mom. “She taught me to be strong, but she also taught me to be resourceful, and to know that I needed to use my head to escape situations that were not healthy.”

That’s why in the wake of the harassment from Thomas, she decided to leave Washington D.C. and go back home to Oklahoma. She notes that for survivors of sexual harassment, the situation is all too similar.

“I quickly realized that Clarence Thomas was someone who could change my career, change my life in Washington, D.C. … Getting out of the situation for me meant leaving the job, and moving back to Oklahoma. And that's really replicated today. And we have so much more knowledge now about what is going on with the problem, sexual harassment. But we know, from research, that 50% of women who are harassed in the workplace will leave their jobs and some will change careers altogether.”

After leaving Washington D.C., Hill says she struggled when transitioning to an educational career in Oklahoma. That’s because the harassment she experienced still weighed heavily on her mind.

“More than just the damage of losing a job or losing income …. there's fear that … on any given day, that person can pick up the phone [and] make a call that could land you out of whatever position that you've taken. So those kinds of things weigh on people who have experienced harassment in the workplace. And it's not uncommon to move and try to get as far away from that possibility occurring in their lives as they possibly can.”

“We know, from research, that 50% of women who are harassed in the workplace will leave their jobs and some will change careers altogether,” says Anita Hill. Photo by Celeste Sloman.

Testifying in 1991 as a Black woman

Hill says she can only speculate whether her testimony would have been received differently if she were white. She points out that her race might have played a role when considering the makeup of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time.

“What we do know is that there were certain people on a committee like a [James] Strom Thurmond, who embraced Clarence Thomas. Strom Thurmond was white. He was a former segregationist. I can't imagine Strom Thurmond embracing Clarence Thomas if his accuser had been a white woman. But all we know is what happened to me. And I do believe that what happened to me involves a certain level of racism against African American women.”

U.S. Senator Joseph Biden (Democrat of Delaware), chairman of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, welcomes Judge Clarence Thomas, center, to the hearing before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee to confirm him as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. on September 10, 1991. Pictured from left to right: U.S. Senator John Danforth (Republican of Missouri); U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond (Republican of South Carolina), ranking member; Judge Thomas; Chairman Biden; and Virginia Thomas, wife of the nominee, can be seen in the lower right corner of the photo. Photo by Arnie Sachs / CNP /ABACAPRESS.COM.

During the hearing, Thomas referred to Hill’s accusations as a “high-tech lynching” and deemed them false accusations meant to hurt his career. Hill denounces that sentiment and says he used racism to divert attention from his harassment.

“I don't think there was ever any account of a Black man being lynched because of an accusation of a Black woman. So there was something really perverse about the ‘high-tech lynching’ excuse that he raised, but it was effective,” she says. “Anytime that you raise the specter of lynching, people recoil, and they should. They should. But that doesn't mean that you shouldn't ask questions, and you shouldn't probe the claim. Because then if you don't, then it becomes a way of silencing all victims. And that is something that we shouldn't tolerate.”

Hill draws comparisons to singer R. Kelly’s racketeering and sex trafficking case and why it took so long to bring his crimes to justice, referencing a recent New York Times op-ed by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

“She argues that in a large extent, it was because all his accusers were Black, that there was a combination of racism and misogyny that made people not believe that Black women could be sexually violated in the way that they were claiming.”

She adds, “When it comes to women of color, we know that they have a higher rate of sexual assault and rape, they have higher rates of murder by partners. … One in every two Native women have experienced sexual assault. … More often than not, those assaults are committed by non-Native men. We can't ignore race when we are addressing the problem of gender violence. What happens is that race layers on top of the misogyny and leaves women of color completely vulnerable.”

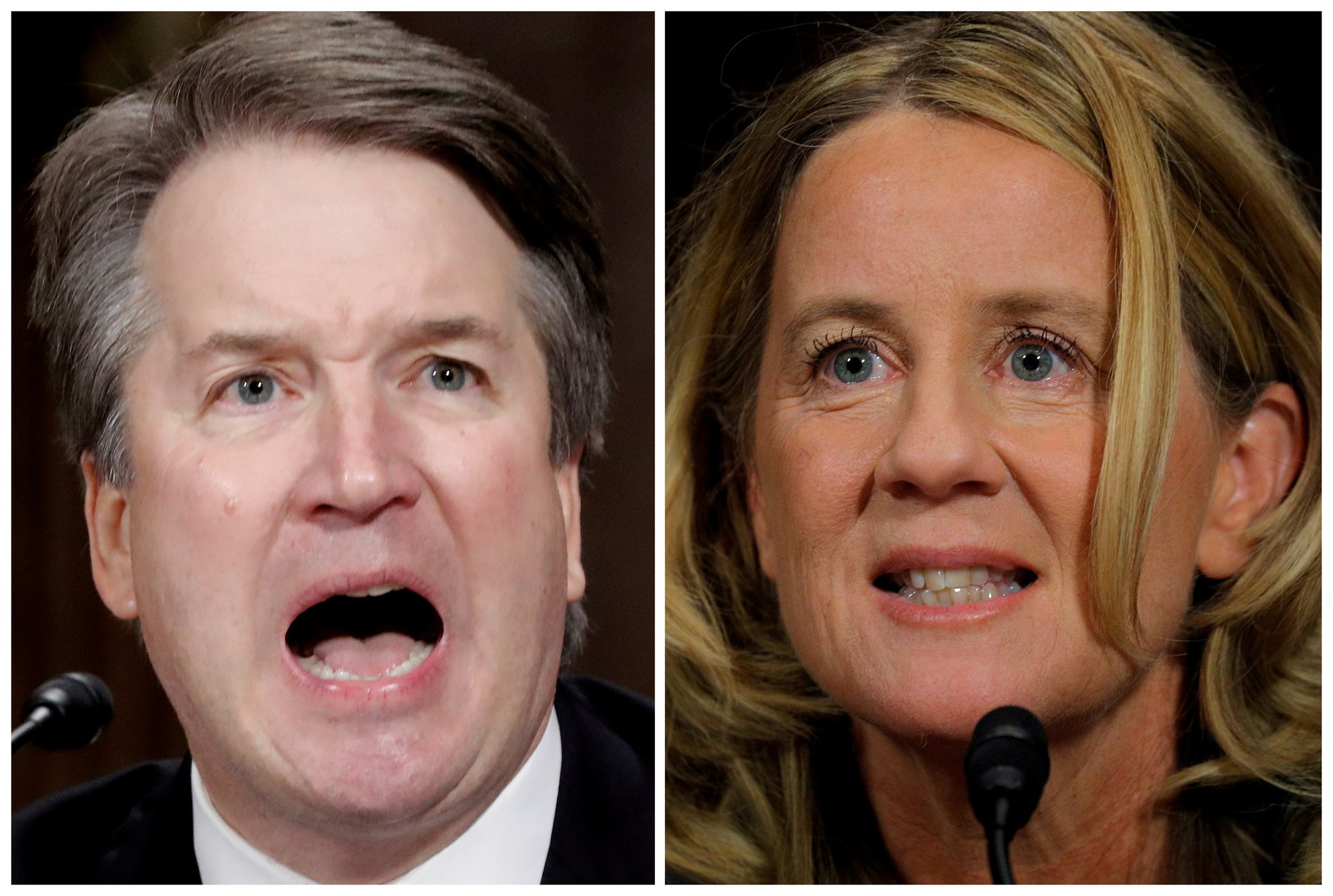

Brett Kavanaugh’s hearing nearly three decades later

When Christine Blasey Ford came forward with sexual assault allegations against then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, Hill says she met with Ford a few months afterward to talk about the fallout of her testimony.

“Our conversation really was about a human conversation. I recognized that Christine Blasey Ford had really gone through an experience that was gonna change her life.”

Hill says that even nearly three decades later, the Senate Judiciary Committee still hadn’t implemented a proper process to address complaints about potential Supreme Court nominees.

“In 1991, there wasn't a clear path for an individual like either of us to go through to address a complaint that we had or the information that we wanted to share about a nominee's character and fitness to be on the Supreme Court. As far as I know … if someone came forward today … there's no process to bring in that kind of information. And with Christine Blasey Ford, as well as with my [case], people are left feeling that our government doesn't care about these issues, because they don't even care to adopt a process to address them fairly.”

Professor Christine Blasey Ford (right) testifies during a Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearing for U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh (left) on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., U.S., September 27, 2018. REUTERS/Jim Bourg/File Photo.

However, Hill notes that the questioning Kavanaugh endured was way stronger than anything Thomas experienced in 1991.

“I think that just shows that you can change the personnel. But if you don't change the process … and if you don't shift some of that power and control so that victims can be heard, then the outcomes are always going to be the same, and the public is going to continue to be disappointed.”

Now that both men sit on the Supreme Court, Hill says that the trust in the Supreme Court has been forever damaged.

“People do not trust an outcome reached that limits the facts. … They're never going to trust the outcome. It's not just the outcome. It's how you get to it. And in both situations, but [especially Kavanaugh’s] there was this manipulation of the investigation to pit her word against his. And what that meant was that you had an individual citizen, like Christine Blasey Ford, going up against the power of the White House and members of the Senate. And you can imagine that it's almost impossible to be her under the circumstances.”

Activists hold a protest in opposition to U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and in support of Christine Blasey Ford, the university professor who accused Kavanaugh of sexual assault in 1982, near Times Square in New York City, New York, U.S., October 4, 2018. REUTERS/Stephen Yang.

Hill adds that the dismissal and manipulation of these types of allegations can play out in other settings.

“What we are learning about is that those kinds of manipulations of processes, or lack of processes, or failures of processes are happening throughout our systems, whether it's an elementary school where children are being bullied because of their gender or their gender expression, or whether we're talking about high school where girls typically are being sexually assaulted, or college where one in every four women who goes to college will experience sexual assault typically in their first or second year, or in our workplaces. These problems exist throughout our institutions. And they exist, of course, in workplaces, public and private, as well as the military. So we've got a huge problem.”

Changing the system now — and not leaving it to another generation

She notes that attitudes and tolerance around gender bias and violence are changing, especially among younger generations, but the systems that perpetuate the issues still exist in the greater society.

“Those systems exist. They continue to exist, and people continue to hurt. So what we are doing is we're bringing people in with different attitudes, but they lack the power to change those systems. Our present leaders in these organizations need to be doing that. ... I'm a baby boomer — shame on us if we just try to kick the can and put this on another generation. We know how much it has hurt us. So we shouldn't leave it to another generation to solve. We can do better.”

She adds, “I have heard over the past 30 years are people, victims and survivors who are suffering from every form of gender-based violence that there is. If we don't address the whole of the problem and look at it holistically, we're not going to be able to protect people from one form or the other. We can't cure one and think, say sexual harassment, and think we're going to be done with all of those other ways that these kinds of behaviors occur.”

Hill says now it’s time to stop grooming young girls into believing that teasing or bullying from boys is acceptable or even an indication of interest. She adds it’s also critical for men to not only be more honest about assault or harassment they’ve received, as well as for society to be able to accept men who have been assaulted.

“Many of them are not honest because they believe they'll be perceived as not man enough to have fought it off. And there's this myth out there involving men that if you didn't fight off your offender, then there's something wrong with you, that maybe you deserve to be assaulted. And we need to acknowledge that it's part of our culture that says that masculinity is the same as aggression.”

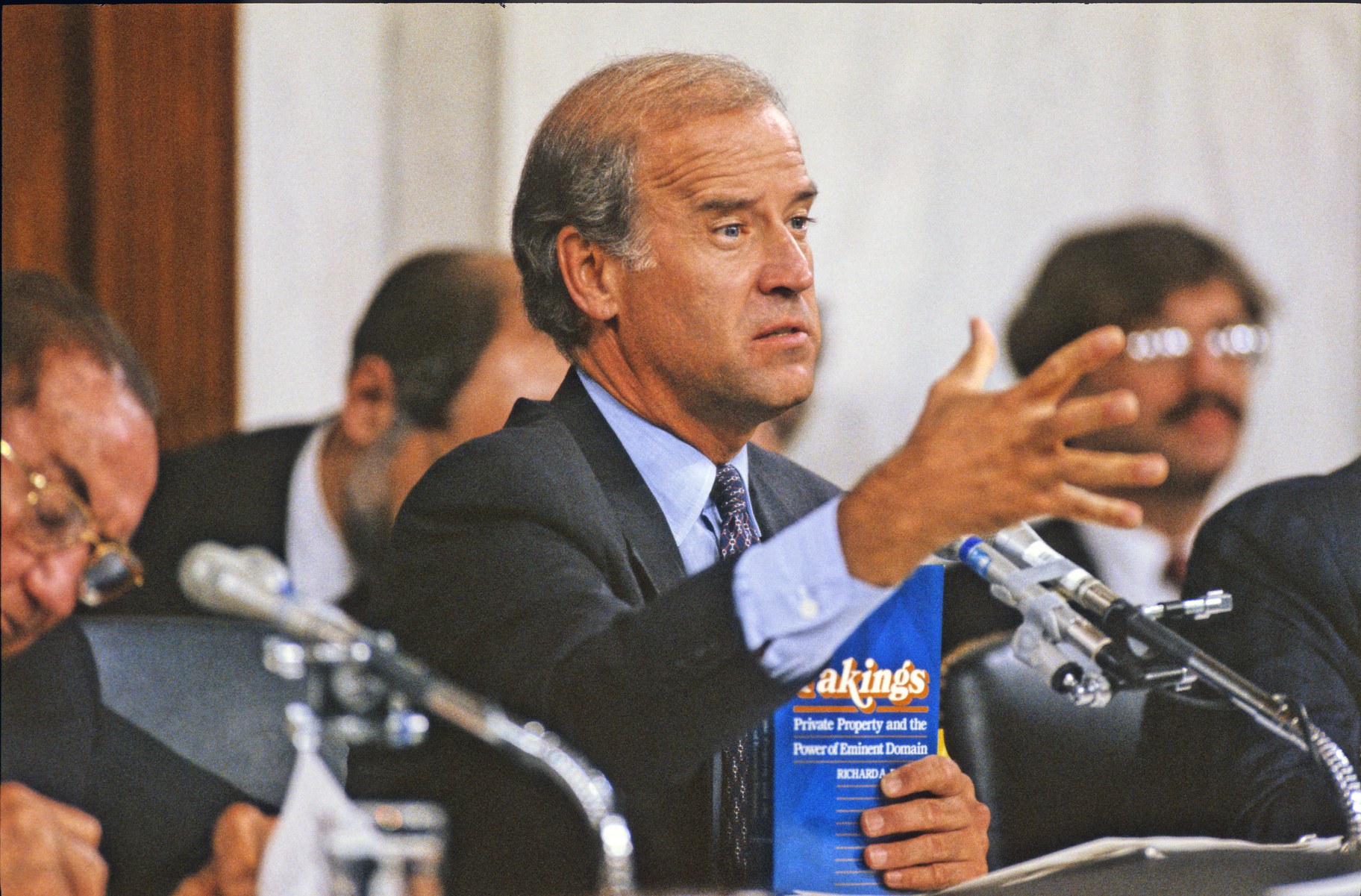

Joe Biden’s apology and gender violence as a public problem

In the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, Biden called Hill and apologized for his handling of the 1991 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing. She says it was an apology that she wasn’t seeking. After all these years, she says she wants an acknowledgment of how widespread the harm that sexual harrassment and sexual assault have on the world at large.

United States Senator Joseph Biden (Democrat of Delaware) makes his opening statement prior to hearing the testimony of Professor Anita Hill during the hearings to confirm Judge Clarence Thomas as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. on October 10, 1991. Thomas was nominated for the position by U.S. President George H.W. Bush on July 1, 1991 to replace retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall. Photo by Arnie Sachs / CNP /ABACAPRESS.COM.

“I wanted him to understand that the harm wasn't just to me, that the harm was to our nation. And that's what I want people to understand that the way we are addressing this problem now is hurting all of us. It's hurting survivors and victims, first and foremost, their families and their supporters. But it's hurting … our institutions that are the communities that exist within schools and within workplaces. It's hurting us economically because we are losing talent, we're losing productivity, whether it's from workplace harassment or intimate partner violence. And we need to understand that that makes it a public problem. We all own it.”

She adds, “That's why our leaders like Joe Biden and leaders of universities and principals and schools and CEOs of corporations need to make getting rid of these forms of violence their priorities. … There's just been a failure to acknowledge. And that's always the first step. You've got to acknowledge that this is a crisis-level problem. And then you can start to understand how we can change our structures to address it.”

Our State of Denial

Far too many claims of gender-based violence, whether sexual assault, workplace harassment, or intimate partner abuse, are closed without a meaningful search for the truth. Often, when we do investigate, we ignore facts that are inconvenient, dismissing them as insignificant. Both failing to probe and ignoring the findings reflect a shared state of denial about the pervasive role of gender-based violence in society. And denial is more than an oversight. It is a strategy that employers, politicians, and judges employ to escape assigning accountability for addressing the problem.

Here's an example of how denial works in terms of women's health. Imagine waking up one morning with pain in your neck, jaw, back, and arms, as well as nausea, sweating, shortness of breath, and light-headedness. You call your doctor hoping to get an appointment right away, but instead he suggests that you may be suffering from anxiety. He recommends that you take an over-the-counter drug like Tums or Prilosec for the stomach problem or Tylenol for your neck and jaw pain. He insists that what you describe "doesn't appear to be too bad-nothing that a few days of rest shouldn't take care of." Your doctor is missing the symptoms of a possible heart attack. I hope you've never encountered this kind of treatment, but unfortunately others have. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, researchers discovered that women were at high risk for misdiagnosed, mistreated, or untreated cardiac arrests, in part because doctors were looking for symptoms that were more common to men-chest pain and pain in the left arm. But another element was the assumption that women were overreacting to their health concerns. As a result of social and medical biases, tests that could have revealed women's heart ailments were never prescribed. Instead, women's cardiac arrests were dismissed as heartburn or a panic attack. Women weren't getting the same quality of treatment as men, the treatment they deserved. The gender gap in treating heart disease is not new. And more than a decade after it was discovered, the gap continues to exist. As a result, women are dying or suffering from life-threatening conditions because they didn't get the proper diagnosis and treatment.

The gender gap in taking women's health concerns seriously isn't limited to heart conditions, as shown in an episode that took place at the Indiana University Health North Hospital. In 2020, in a video posted on Facebook, a Black woman physician, Dr. Susan Moore, complained that a White doctor who was treating her for COVID-19 denied her request for pain medication. Not taking Moore's word about the level of pain she suffered, he challenged her to prove that she was in as much distress as she claimed. And instead of the treatment she asked for, he recommended she be sent home. Moore eventually was treated for pain, but not as she had requested. About two weeks later, Moore died from complications of the coronavirus infection. Following a preliminary review of the case, the hospital's CEO expressed his full confidence in the "technical aspects of the delivery of Dr. Moore's care." However, he called for an external review and expressed concern that the medical team "may not have shown the level of compassion and respect we strive for in understanding what matters most to patients." So would an external review tell us why Dr. Moore didn't receive the "compassion and respect" she believed she deserved? Perhaps. Moore had attributed the rebuff to racism. But the brush-off she got could have stemmed from sexism or from racism and sexism combined. A similar disregard occurs when women complain about workplace sexual harassment and assault. And most organizations review their complaint-handling processes internally, even when there are multiple accusations against an individual. As with health issues, sexism, organizational loyalty, and a host of other biases lead some internal investigators to disrespect women who complain. Far too often, concerns go uninvestigated or are shoddily probed and dismissed as insignificant. And as with prejudging women's ability to communicate their medical conditions, when we discount women's credibility to describe gender violence, the outcomes are the same. Women suffer-regardless of whether the prejudice is overt or implicit.

"But I Don't Know the Facts"

The very first national attempt to get the facts about sexual harassment in the workplace did not come from federal agencies. In 1976, after hearing about readers' experiences, the popular women's magazine Redbook conducted a survey of nine thousand women, the first of its kind to explore the reality of women's workplace experiences. The magazine's report on the findings was called "What Men Do to Women on the Job." Redbook called the findings "eye-opening." Between ads for Dynamo and Ivory detergents and Arthur Murray dance lessons were accounts of sexual comments, groping, leering, extortion, and more. More than eight thousand of the women who responded said they had experienced at least one form of sexual harassment. Claire Safran, the article's author, concluded that the problem was "a pandemic-an everyday, everywhere occurrence."

Five years after hearing from women employees, Redbook teamed up with the Harvard Business Review to collect business executives' views on sexual harassment in American workplaces. The following are three telling responses from the two thousand men and women who participated in the follow-up study.

"In my own circumstances, sexual harassment included jokes about my anatomy, off-color remarks, sly innuendo in front of customers-in short, turning everything and anything into a sexual reference was an almost daily occurrence," said a thirty-four-year-old first-level female manager in environmental engineering for a large producer of industrial goods. "I have just left this company [a big chemical manufacturer] partially for this reason," she added.

Another person, a fifty-three-year-old man who was a vice president at a medium-sized financial firm, said he was skeptical about sexual harassment existing within his company. "I used to believe it was a subject that was being exaggerated by paranoid women and sensational journalists," he said. "Now I think the problem is real but somewhat overdrawn. My impression is that my own company is relatively free of sexual harassment. But I don't know the facts."

"This entire subject is a perfect example of a minor special interest group's ability to blow up any 'issue' to a level of importance which in no way relates to the reality of the world in which we live and work," said another man, a thirty-eight-year-old plant manager for a large manufacturer of industrial goods.

In the 1981 survey, 88 percent said that sexual relations, even consensual ones, had "no business in the business world," and 78 percent called propositions to swap sex for good performance reviews sexual harassment. The three statements above offer just a glimpse of what the business world thought of harassing behavior. Each sentence describes either a firsthand experience with harassment, reactions to harassing behavior, questions about its significance, or denials of its existence. Which of these perceptions accurately reflect reality in 1981? The truth is that they all do, and the comments can serve as a starting point for determining where we are today.

Excerpted from “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence” by Anita Hill