California’s newest infrastructure project will hit two proverbial climate birds with one stone. And Los Angeles city officials just decided last week to try one of its own.

The plan is to cover some of California’s exposed water canals with solar panels. It will prevent evaporation amidst the state’s historic drought. It will also create renewable energy as the state attempts to meet lofty decarbonization goals.

Piloting a win-win

The idea gained traction in California after researchers at UC Merced studied the possibility on the state’s canals last year.

“If we put solar panels over all 4000 miles of California's open canals, we estimated we could save 65 billion gallons of water annually,” says Brandi McKuin, who led the study. “That's enough for the residential water needs of 2 million people – enough to irrigate 50,000 acres of farmland.”

Researchers found the panels could also generate 13 gigawatts of renewable power. That’s about half of the capacity needed by 2030 to meet the state’s goals. “The political wind is at our back right now and that’s another reason this is gaining traction,” she says.

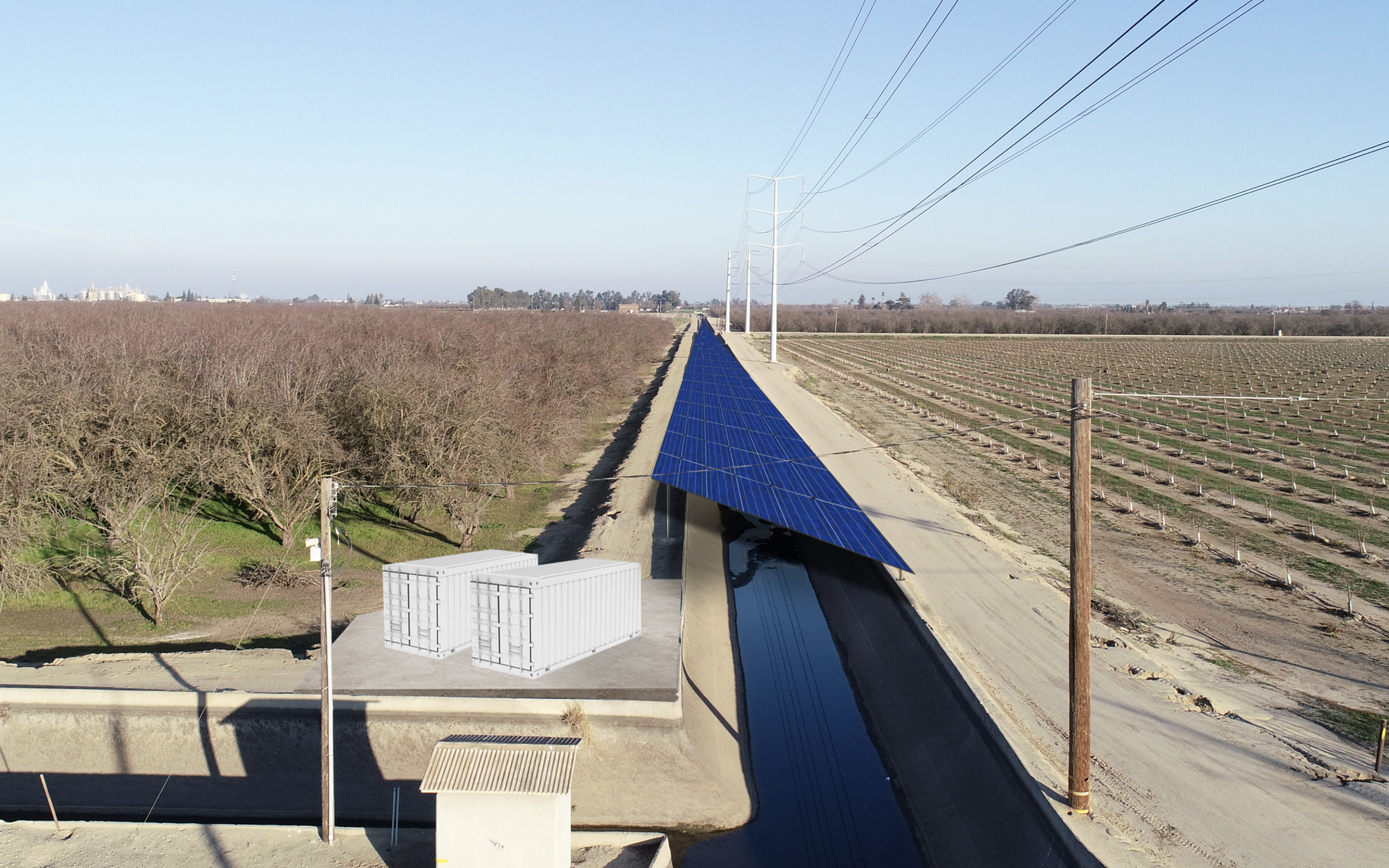

It’s gained so much traction that the Turlock Irrigation District in Northern California is breaking ground on its first solar canal installation as soon as the equipment arrives early next year. They will try it out on a couple miles of their canals first.

“We thought we were the absolute perfect agency to pilot it, since we're both the water agency and the electric utility,” says Josh Weimer, external affairs manager with the Turlock Irrigation District.

The pilot project in Northern California will test a variety of canal widths and solar panel types. Photo courtesy of Solar Aquagrid 2022.

Besides the water and power benefits, Weiner says they’re hoping the solar panels will stop weeds from growing in their aqueduct. “We spend over $1 million a year to clean our canal system to make sure that those weeds are not blocking drops or side gates that really would jeopardize the reliable delivery of irrigation water,” he says.

It also skirts around one of the biggest problems with solar energy: land use. Large solar farms can disrupt the habitat of plants and animals that live there. Where there are canals, there’s already ecological disruption, so there’s no added ecological harm to add panels on those acres. Plus, covering state-owned aqueducts with solar panels means no one has to buy or rent a new piece of land.

Lessons from the other side of the world

A similar project in India is more than a decade old. The first project only covered 750 meters and produced about a megawatt of power, but they’ve added several more projects since then. It’s an idea that makes a lot of sense for California: We’ve got the largest state water project in the country. Most of the state’s water comes from the northern half of California, and most of it gets used in the southern half.

Like any new idea, it’s not without its hurdles. The project with India came with lessons on what not to do: Don’t use expensive, cumbersome steel to hold up the panels, which corrodes over time. And don’t install panels that are difficult to move, which makes cleaning it pretty difficult.

“It inspired us to look for a design that would be lightweight, less material and allow access, and so our designs are cabled steel suspension, and they're at least 50% less material, 50% less weight,” says Jordan Harris, co-founder of Solar Aquagrid, the company in charge of figuring out how to install California’s first project.

Bringing solar canals south

Last week, the Los Angeles City Council voted to investigate funding a similar project over the LA Aqueduct, which is hundreds of miles of canals snaking their way from the Owens Valley down to LA, supplying our dry climate with the water it needs to support the millions of people who live here.

Councilmember O’Farrell, who chairs the City of LA’s committee on energy, climate change and environment justice, introduced a motion to essentially copy what’s happening up north.

“We thought, ‘Well, wait a second, we've got 370 miles of an aqueduct. How about we do it here too?’” he says. “How come no one thought of this before? I chuckle because it is so obviously a path that we should head down and fully investigate.”

The proposal to cover exposed sections of the LA Aqueduct like this one in Sylmar would save enough water to support about 4,000 homes each year. Photo by Caleigh Wells.

O’Farrell says about 10% of LA’s water gets lost to evaporation. Covering the LA Aqueduct could save enough water to satisfy the needs of roughly 4,000 homes. The solar panels could generate up to 100 megawatts of solar power, which is enough to power tens of thousands of homes, he says.

“We're looking at the cliche of the lowest hanging fruit – and this is certainly one of them – because it could bring power from the rights of way that we already control right into the urban core of the city of Los Angeles,” he says.

Plus, solar panels floating over water are actually about five percent more efficient than solar panels floating over land. It keeps the panels cooler so they work better.

But solar over canals also comes with its downsides.

“Installation costs are high. And when I mean high, I'm talking about an order of magnitude five to six times higher than if you were to install ground mount,” says LADWP Power Engineering Manager Arash Saidi.

That added cost would normally get passed onto the ratepayers, but O’Farrell says for now, federal money set aside by the Biden administration for infrastructure projects can fund this one.

The other problem: Transmitting electricity generated from a set of solar panels in the middle of nowhere isn’t an easy task.

“This is 62 miles, if we run 62 miles of cable, you're going to have immense losses, especially at lower voltages.” Saidi says.

The possible solution to that is providing the power from the solar panels to homes near the canals, so the electricity is not traveling as far.

There isn’t a great timeline yet for when the panels will cover the LA Aqueduct. But O’Farrell is optimistic. For now, LA is on track to meet its goal of having 100% renewable energy by 2045. And solar canals will bring the city one step closer.

I've always thought of this as a spiritual quest. And I'm excited about it,” he says. “The roadmap is there, it's very clear. And we know we can do it.”