On Platform Holly, off the shore of Goleta, lives a jumble of pipes, cranes, ladders, storage containers, and dozens of crew members. They roam the walkways. Motor up to the structure by boat and you can see them offloading cargo, or injecting the oil wells with cement to seal them. At the base of the platform, pelicans and cormorants gather along the catwalk. Sea lions jump onto the lowest deck for some midday sun.

This structure has been pumping oil out of the ocean floor for nearly 50 years, from the time it was built in 1966 until a nearby oil spill in 2015 shut it down for good. But that doesn’t mean the platform will necessarily go away. Some biologists and fisherman hope that Holly and other similar oil platforms are left in place to host underwater communities of marine life for decades to come.

Sea lions hang out next to Platform Holly. Photo by Kathryn Barnes.

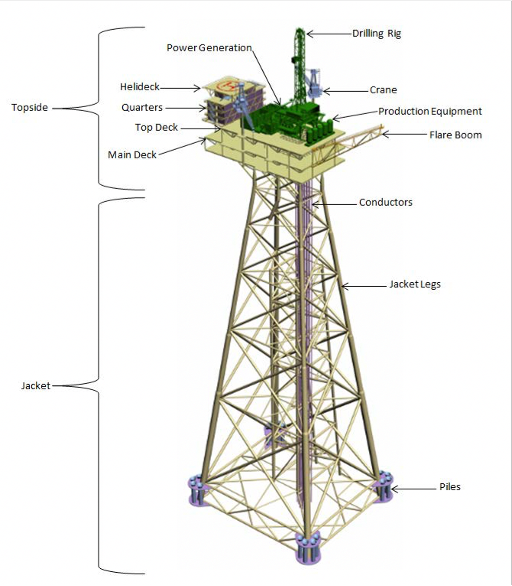

Oil platforms off California’s coast sit in depths of water ranging from 200 to 1,200 feet. A plethora of marine species live on and around the jacket legs. Graphic courtesy of Ann Bull/Marine Science Institute/UCSB.

There are 23 oil platforms off Southern California’s coast that were installed between the late 1960s and early 1990s and will eventually need to be decommissioned. Eight of them are set to be decommissioned in the next decade, according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. Platform Holly is one of them.

Oil companies agreed to safely and securely cap and abandon their offshore wells as part of their initial lease agreement with the state and federal government when these platforms were first built.

But the fate of the structures themselves has yet to be determined.

“There are three endpoints to platform decommissioning, and this is worldwide,” says Milton Love, a marine biologist in Santa Barbara. “At the extremes, you can leave a platform completely in place, sticking up above the water, with offices or whatever you want. The second possibility at the other extreme is complete removal. And then something in the middle is leaving part of the jacket in place.”

Each of those three options – no removal, full removal, and partial removal – have their supporters. Ultimately, it’s up to the state to decide.

No removal

Jeff Maassen has been fishing and urchin diving in Santa Barbara for 35 years. He’s arguing for no removal. Under the water’s surface, he says these steel jackets have become a rich marine habitat.

“In the shallows, you get the mussels and barnacles like you would on the beach. And as you go deeper, you get more invertebrae. I've seen urchins living on legs. And then you get the anemones and then the fish. It's just all here in one place.”

At low tide, you can see mussels and other shellfish attached to Platform Holly’s legs. Pelicans like to hang out, too. Photo by Kathryn Barnes.

Fisherman Jeff Maassen would like to see the oil platform structures stay once they’re decommissioned so that he can “aquastead,” a riff on farmsteading. Photo by Kathryn Barnes.

Above the water, he says, the structure provides shade for the organisms below, and a refuge for sea lions and birds. And just like crew members on Holly live and work on the platform while capping those wells, he sees a future where marine biologists and fishermen like himself could stay as they do research or farm the urchin and mussels growing below the surface.

“To remove all of it, then you would have no place to conduct science or research, or [do] aquaculture, or experiment with other new technologies,” he says.

But who would take on the costs and liability for all of that? The oil company won’t pay to maintain the full platform once it’s decommissioned, nor does the government want to take that on.

Full removal

Anti-oil groups like Get Oil Out argue for a full removal of decommissioned platforms. They say oil companies need to uphold the contract they signed by taking all aging oil infrastructure out of the sea.

But Love, the marine biologist, says full removal comes with some ethically questionable trade offs.

“Killing all that marine life is immoral, in my view,” he says. “It’s basically killing them for a bad career move. You happened to settle on a piece of steel instead of a rock, and so you have to die.”

Sea life is seen on Platform Gilda off Ventura’s coast. Photo by Scott Gietler.

Plus, he says, how do you transport and dispose of steel legs, some as tall as the Empire State Building, covered in rotting sea life? What landfill or recycling facility will take that?

“That ain't gonna happen in the United States so you're going to have to take them to China. You're gonna have to take them to Bangladesh. All of that fuel being burned, all of that pollution,” says Love.

Partial removal

According to Love, the research seems to support partial removal. That most likely means cutting the platform at about 85 feet below the waterline so that some of the marine habitat can stay in place, but boats can easily get by and the costs and liability of the structure diminish.

In other words, it becomes an artificial reef, hidden to land-based eyes and known only to sea life (and the occasional diver).

This idea is catching on. The Environmental Defense Center, an environmental advocacy group in Santa Barbara, used to advocate for full removal, but new science showing that some underwater rigs foster thriving marine habitats has changed minds there.

“It's really unique because these are manmade structures in the ocean that have had a history of environmental degradation, yet when you get under the surface they have these mussels and sea anemones and sea stars and all sorts of critters, which tug at people's heartstrings,” says Kristen Hislop, the organization’s senior director of the marine program.

A Copper rockfish swims under an oil platform. Photo by Scott Gietler.

In 2010, the state legislature passed an Artificial Reef Program allowing oil companies to convert a decommissioned platform or production facility into an artificial reef if it provides a net benefit to the environment compared with removing it entirely.

There are still lots of details to work out, which is why the decision-making process will span years for Holly alone.

“I like to describe this topic as a choose your own adventure, and it really matters how it all plays out,” says Hislop. “Where do we cut these off? Do we leave them in place, or do we topple them? Do we tow them to a location that makes more sense for an artificial reef? And once they are artificial reefs, do we protect them, or do we fish them?”

Since Platform Holly sits in state waters, it’s up to the State Lands Commission to ultimately decide which adventure to choose.

A feasibility study for all three options, plus an environmental review, is expected to start later this year, and the state will be asking for your input. For the other platforms farther offshore, the federal government will have a say.

Meanwhile, this week the Santa Barbara Board of Supervisors voted to deny ExxonMobil’s request to truck oil coming from its platforms off the coast of Goleta, which could lead to even more decommissioning in the future.