On the streets of LA's Skid Row neighborhood, the sights and sounds of people fighting and in trouble because of mental health problems, often combined with drug and alcohol addiction, can be constant.

But in quieter conversations away from the conflict, Skid Row is also a place where people can be remarkably candid about the mental illnesses that have defined and destroyed their lives.

“I'm manic depressive, bipolar, with severe psychotic features,” says Zenobia, who doesn’t want her last name used because of past problems with the police.

Zenobia, who’s in her 40s, says she’s been living on the streets for years because of her mental problems. And those problems, she says, have sometimes made her a threat, both to herself and to others, like when she attacked a security guard in the neighborhood during a psychotic episode.

“The man didn't even do nothing to me, but in my mind he hit me,” says Zenobia. “So I … came back and I hit him. It would have caused me going to prison for six years as a felony.” Zenobia says she narrowly avoided being charged because of the intervention of mental health workers.

It is these kinds of problems that California’s new mental health court system is supposed to tackle. It’s the biggest and most controversial change to how the state deals with mental illness in decades.

Proposed by Governor Gavin Newsom, the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court system requires all counties in the state to create first-of-their-kind mental health treatment courts. In them, people who have the most serious untreated mental health problems, like schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, will appear before judges and could be ordered to receive treatment and medication, even if it’s ultimately against their will.

Los Angeles County, the epicenter of the state’s mental health crisis, has promised the state it will have its CARE Court up and running by December 1, a year earlier than originally proposed.

The need is overwhelming.

“I think just looking at our numbers, it's staggering,” says Lisa Wong, the new director of Los Angeles County’s Department of Mental Health. “Our estimate is that LA County alone is probably going to get 7,500 petitions, resulting in 6,000 people who will qualify for CARE Court.”

But Wong worries about finding enough trained personnel to get CARE Court up and running. The county will build upon existing mental health outreach programs. But still, finding professionals who want to do the in-the-streets mental health assessments and months-long counseling follow-up that CARE Court will require won’t be easy.

“It's a little intimidating,” says Wong. “We're going to need probably anywhere from 600 to 800 staff to be able to do CARE Court at the volume we anticipate. … During COVID, people made lifestyle decisions, and a lot of people went to telehealth or got out of the field of public mental health altogether.”

Along with finding enough trained staff, there are other very basic unanswered questions about CARE Court’s rollout in LA County.

Such as: Where will the lawyers come from who are supposed to represent the rights of the indigent mentally ill placed in the CARE Court system?

LA County Public Defender Ricardo Garcia says his office hasn't even been told yet whether its attorneys will represent people in CARE Court or whether that work will be farmed out to local public interest law groups.

“Assuming we had CARE Court, the expectation will be that we will need additional attorney staff, social worker staff and paralegal staff,” says Garcia. The office’s public defenders say they’re already overstretched and overworked without added CARE Court responsibilities.

Getting buy-in from the people most affected

Relatives of the mentally ill will have the authority to refer their loved ones into the CARE Court system along with first responders and mental health clinicians, and some of them view the new program as a long overdue lifeline.

Harold Turner is one of those supporters. His now-adult daughter has struggled with mental illness since she was a teen, and in one psychotic episode even stabbed her sister.

“She had a breakdown and was arrested, but my goal was to get her into treatment and away from prison,” says Turner.

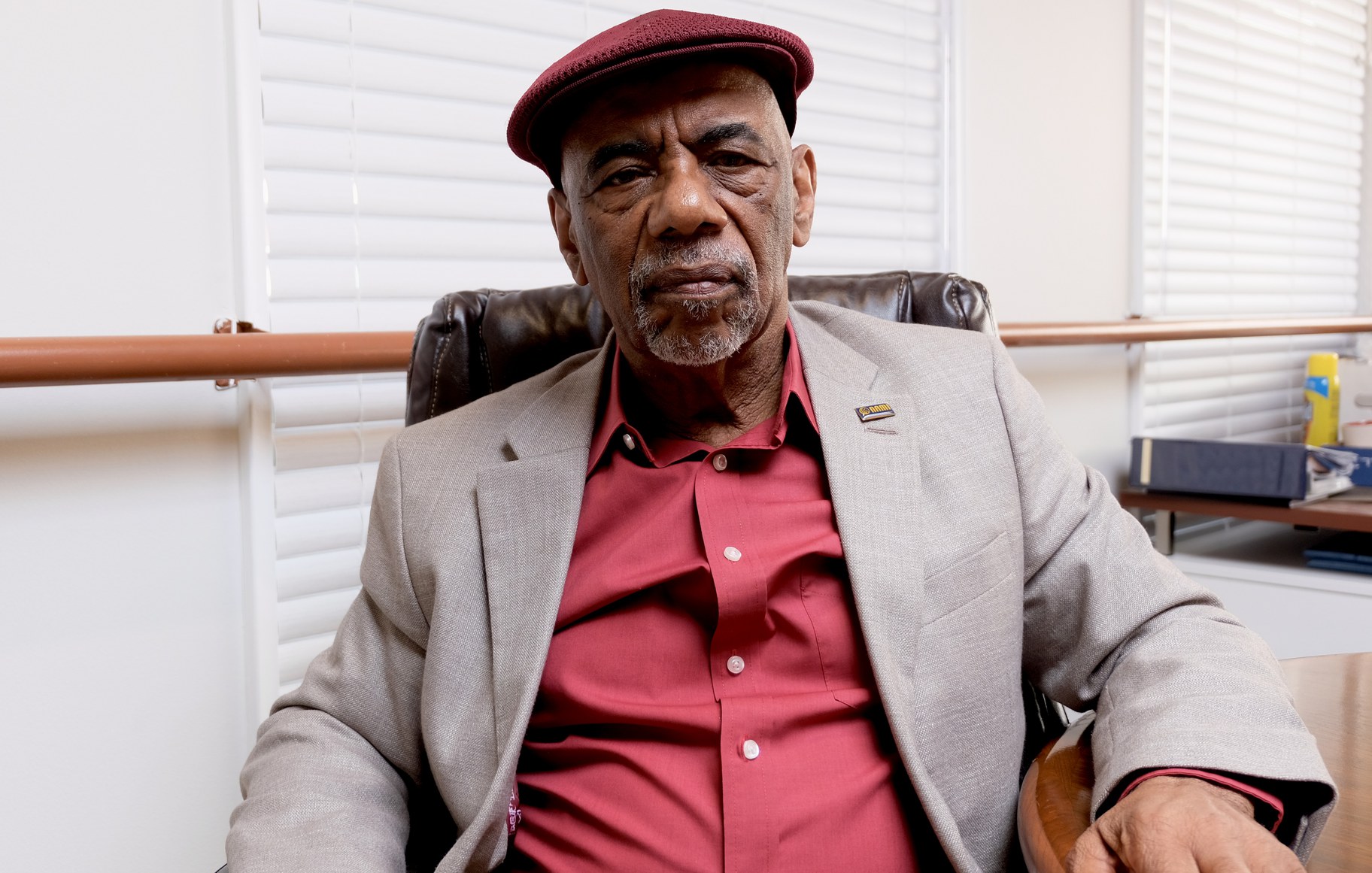

Turner, executive director of the Urban Los Angeles chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, says he encountered a justice system in LA County that was more interested in punishing his daughter with time behind bars than getting her mental health treatment.

He thinks the CARE Court system will change that, especially for poorer people of color who may not get the mental health help they need.

Executive director of the Los Angeles urban chapter of the National Alliance on Mental illness Harold Turner is a strong supporter of CARE Court, arguing families of the mentally ill often have nowhere to turn for help. Photo by Saul Gonzalez.

Turner says when he went to court for his daughter's case, he watched too many other people with mental problems not receive help.

“I can't tell you how often I sit in that courtroom and watch young Black and Brown men who should be going into treatment — go out that back door to prison," says Turner.

But CARE Court also comes with a stick, which he supports. Those referred into the program who don’t participate in ordered treatment might be placed into conservatorships and forced into treatment and the taking of medications. “I have no problem with that,” says Turner.

But a lot of other people do, given the history of past abuses in the mental health system, including coercive treatment, that stretches back generations.

“We don't need more deprivation of liberty for folks with disabilities. That's going in the wrong direction, not the right direction,” says Kath Rogers, an attorney with the ACLU of Southern California.

The ACLU supported a challenge to CARE Court filed by civil and disability rights groups and recently rejected by the California Supreme Court. The ACLU says it and its allies will pursue other legal challenges to CARE Court because the new program risks violating people’s rights to due process and privacy, and perpetuates a stereotype that the seriously mentally ill don’t want help.

“Service resistance is really a myth,” says Rogers. “So rather than having a new civil court bureaucracy that's going to traumatize folks who are already vulnerable … we need to invest in things that work and that really help people.”

What works, says Rogers, is getting mentally ill people who are homeless into housing first, and then treating their mental illnesses with voluntary wrap-around social services.

Kath Rogers is a staff attorney with the ACLU of Southern California’s Dignity for All project, which advocates on behalf of the homeless mentally ill. She worries that CARE Court could infringe on the civil liberities of those with severe mental illnesses. Photo by Saul Gonzalez.

But Harold Turner says those kinds of criticisms of CARE Court are academic and detached from families’ real-world experiences with mental illness.

“I talk to families who would be happy as hell if they could get their family member to even care about their rights," says Turner. “They don't care about their rights. They’re too busy making life miserable for their families, virtually holding families hostage in their house.”

Back on Skid Row, a number of people know about the CARE Court debate and they have lots of different opinions.

One Skid Row resident who calls herself Ruby and has wrestled with her own mental illness — worries about CARE Court’s potential to abuse people’s rights.

“I’m really wary of that kind of thing,” says Ruby, “because you don’t want people coming through and just gathering people up in some sort of cattle call. People have a right to their own self-determination.”

But Zenobia says she supports the Care Court approach, including, if necessary, compelling some mentally ill people to get treatment.

“You see they're not mentally capable of making the decision of whether they need help,” says Zenobia. “But I think if they are really that far gone mentally, that they should step in and intervene.”

Zenovia also offers a word of advice to officials preparing to turn CARE Court into a reality.

“You have to put forth the people who have the empathy to deal with these people, " says Zenobia. “The people who really care about helping these people. You have to meet people where they are, no matter what it is.”