Ron Batiste apologizes for taking breaks while talking. Today, he says, it’s difficult to get a full breath.

The 72-year-old is sitting at his kitchen table in West Long Beach. He’s never been diagnosed with a lung condition, but still, this happens sometimes. Part of the problem is his neighborhood’s worsening air quality.

“I do my best not to be outdoors,” says Batiste. “It's not safe. There was a time when you could stand on Ocean Boulevard and see the ocean. Now you can’t.”

The air has been dirty here for years, and the biggest single source of pollution is the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. A record number of ships and cargo arrived at the ports last year, causing a supply chain backlog that grabbed national attention during the fall. All that activity also increased toxic emissions, which sit in a cloud over Batiste’s home, and when the wind is right, the entire region.

The ports have a long-term plan to clean things up with electrification, but until the backlog is solved, emissions will be higher than normal. For residents like Batiste, who lives within two miles of not only the ports but also a truck yard, railyard and oil refinery, this is concerning. He suspects these are the causes of the grime that collects daily around his sliding glass door and the air conditioning vent, despite using an air purifier.

Batiste shrugs off his own health issues. He’s more anxious about the neighborhood kids and their health. USC studies have shown living in an area like this with high pollution causes measurable lung damage in children.

“It's no fun for me, an older person able to see the effect on younger generations,” says Batiste. “After all, that is our future.”

Dr. Elisa Nicholas, a local pediatrician, agrees. This kind of environment is concerning for anyone, but children take more breaths per minute than adults. “And so when they're exposed to pollution, it has more effect on their lungs than an adult because they're getting a higher dosage of air pollution,” she says.

Nicholas serves mostly low-income families in the portside communities of Wilmington, San Pedro and West Long Beach, areas that are majority Black and Latino and face higher than average asthma and cancer rates related to air pollution. Nicholas calls this an environmental justice health equity issue.

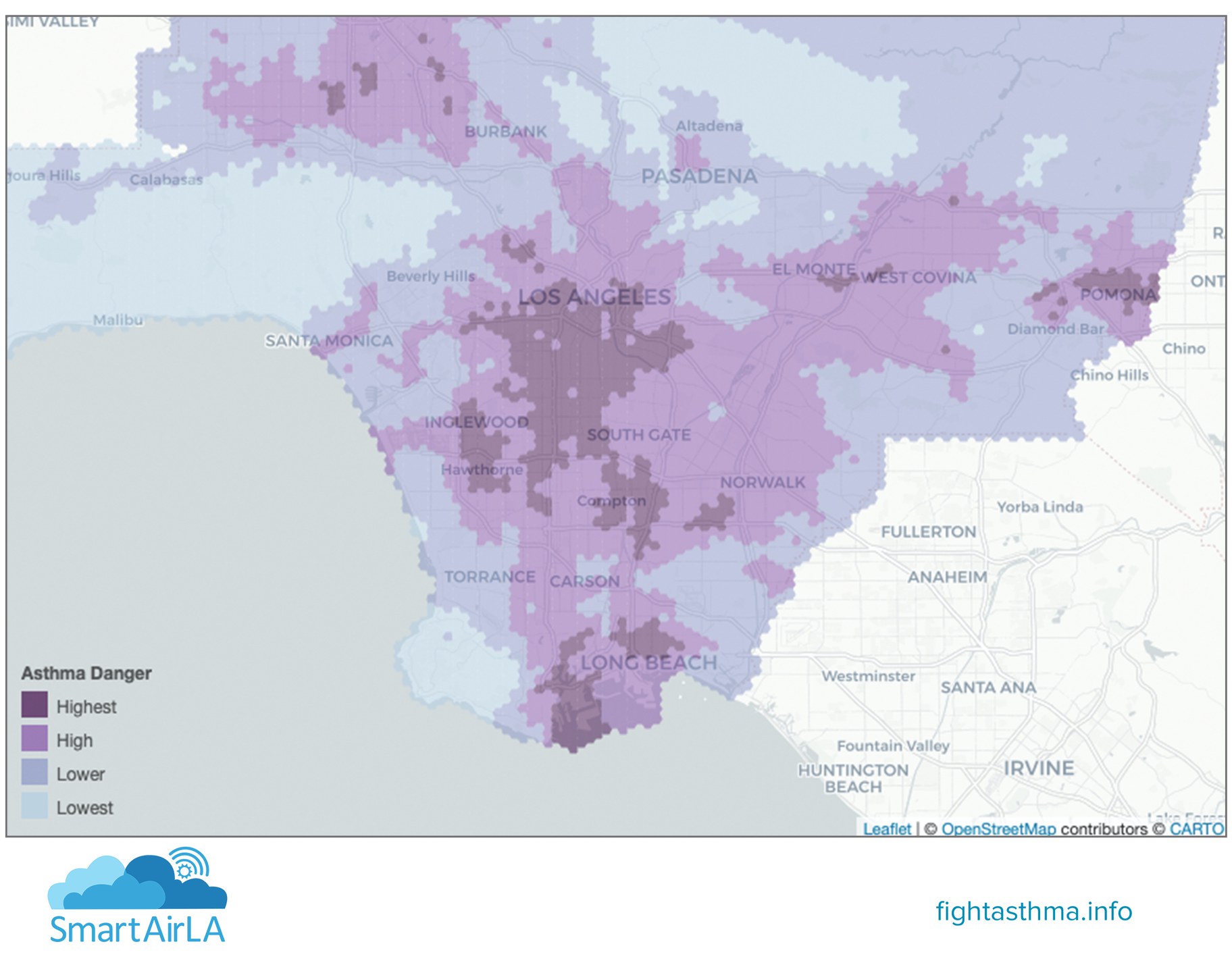

The FightAsthma Danger Tracker shows asthma danger areas in Los Angeles County at the census tract level. Image courtesy of SmartAirLA.

Overall, the state tallied big jumps in emissions from the ships, trains and trucks associated with the ports in the first half of 2021. According to the California Air Resources Board, the increase in the diesel particulate and smog was equivalent to adding 100,000 diesel trucks and 5.8 million passenger cars to the road. With the number of ships at the port doubling, the state estimates there were 20 premature cardiovascular deaths linked to air pollution from fumes coming onshore. The ports broke records for the number of containers they processed in 2021, so the pollution totals for the entire year will be even higher.

But it wasn’t supposed to be this way. Before the pandemic, the ports were making some progress toward cleaning up before the backlog, through measures such as requiring ships to use lower emission fuels and plug into electric shore power when they dock at the ports.

Emissions could stay high through the end of this year, says Chris Cannon, the Port of LA’s director of environmental management. The quickest way to get back on track is to clear out the backlog, which should happen sometime this year. “We hope that means our emissions numbers will start to be better,” says Cannon. “And certainly, in 2023, we hope our numbers are back to normal.”

Port of Long Beach Executive Director Mario Cordero is taking the long view on emissions cleanup. “It certainly is not going to be in the short term as people would like. … But again, let's look at what we've been able to do in terms of the last decade, and what we're committed to do in the next decade” he said at a December press conference.

Adrian Martinez, a lawyer at the environmental law firm Earthjustice, says it’s not a question of whether the ports are doing something or nothing.

“The question is: Are they rising to the moment, this air quality crisis we're in?” says Martinez. “If you talk to the folks who live down in the harbor, talk to the environmental groups, talk to the air agencies, it's clear the answer is no.”

Martinez says the will to clean up the air is not as strong as the will to get things where they need to go fast. For example, Martinez points to how quickly the ports responded to President Biden's call to clear out the backlog in November 2021. Within weeks, the ports created a fine for containers that sat too long in port yards. Meanwhile, it took five years to approve a much smaller fine for high-emission trucks.

Clean air advocates say now is the time for the local air quality board to step in and regulate the ports. The South Coast Air Quality Management District was working on this last summer until the supply chain issues got in the way.

Cannon, from the Port of LA, says he knows the portside communities are frustrated and would like to see faster progress. “We would like to go faster, too,” he says. “But just moving the science along does take a little bit of time. People should know we're doing our best, and we're pushing as hard as we can.”

The long-term solution for cleaning up the air is to rapidly electrify the port.

Five years ago, the ports committed to doing this on a 20-year time frame. Their big goals include switching to zero emissions cargo handling equipment by 2030, and to zero emissions cargo trucks by 2035.

And they’ve made some progress. The ports say together, they’ve added 80 pieces of zero emissions equipment, like tractors and forklifts. And there are now 37 zero-emissions cargo trucks on the road joining the diesel fleets that make over 700,000 truck trips each month.

But the ports haven’t done more because the technology is limited and expensive, Cannon says, and requiring more electric trucks would be an unfair burden to the rest of the logistics industry. “Our goal over the next ten years is to serve as a testbed for the testing and development of zero emissions equipment.”

Theral Golden, a member of the West Long Beach Neighborhood Association and clean-air activist, shakes his head when he hears that the ports have a 10-year plan to clean up the air.

“They act like they [are] running a business,” Golden says. “These are public institutions, and we have public institutions assaulting the public.”

Golden has lived in this area for 50 years. He would like to see a third party regulate the port’s progress toward lower emissions and measure success by how many premature deaths are prevented.

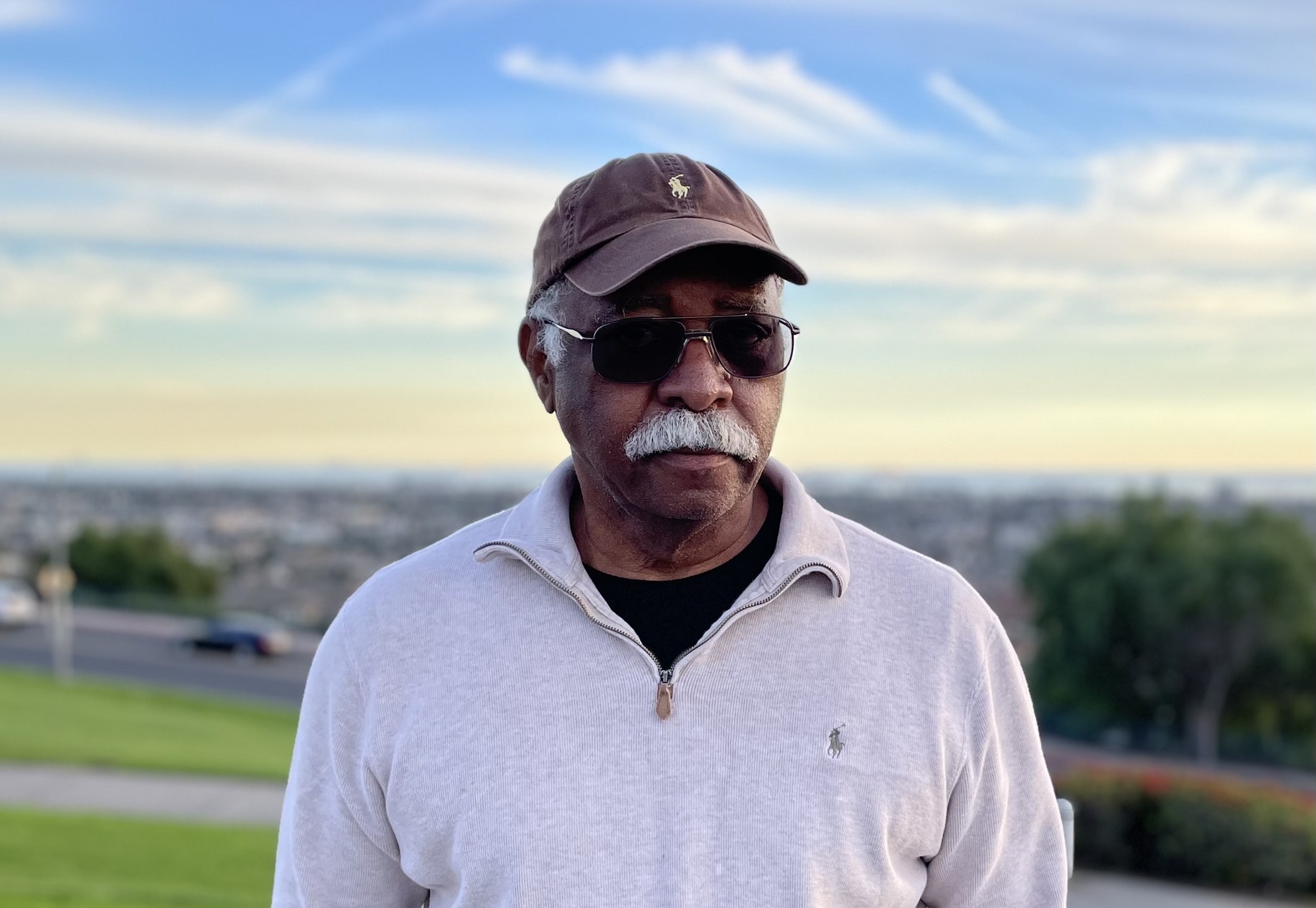

Theral Golden, a West Long Beach resident of 50 years, is a clean air advocate and treasurer of the West Long Beach Neighborhood Association. Photo by Megan Jamerson/KCRW.

The sun is starting to set as Golden stands at Hilltop Park in the East Long Beach neighborhood of Signal Hill, where he has a panoramic view of the ports. Looking at the sky above a dozen ships anchored at sea, he points to the brown haze of smog accumulating over the ships waiting to be blown inland.

“We should not be bearing the brunt of the trade industry on our backs,” he says. “That's what it boils down to at the end of the day.”