Malibu was the private domain of one woman 100 years ago. A champion land preservationist and the scourge of squatters and railroad men, May Rindge fought the longest court battle in California history in an attempt to keep coastal Malibu all to herself.

She lost it all in the end, but in a sense, she also won.

May Rindge rode the range with a revolver by her side at all times, and had a horse named Dave,” says Malibu writer Suzanne Guldimann. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Guldimann Collection.

“Queen of Malibu”

The story of how and why May Rindge spent decades fighting to keep a public road from running along the Malibu coast starts thousands of miles away, on a Michigan farm. There, May Rindge was born into poverty as Rhoda May Knight, the oldest of 13 children.

“She had this sense from the get-go that life was a struggle. You have to take what's yours. ... No one's going to give it to you,” says David K. Randall, author of “The King and Queen of Malibu.”

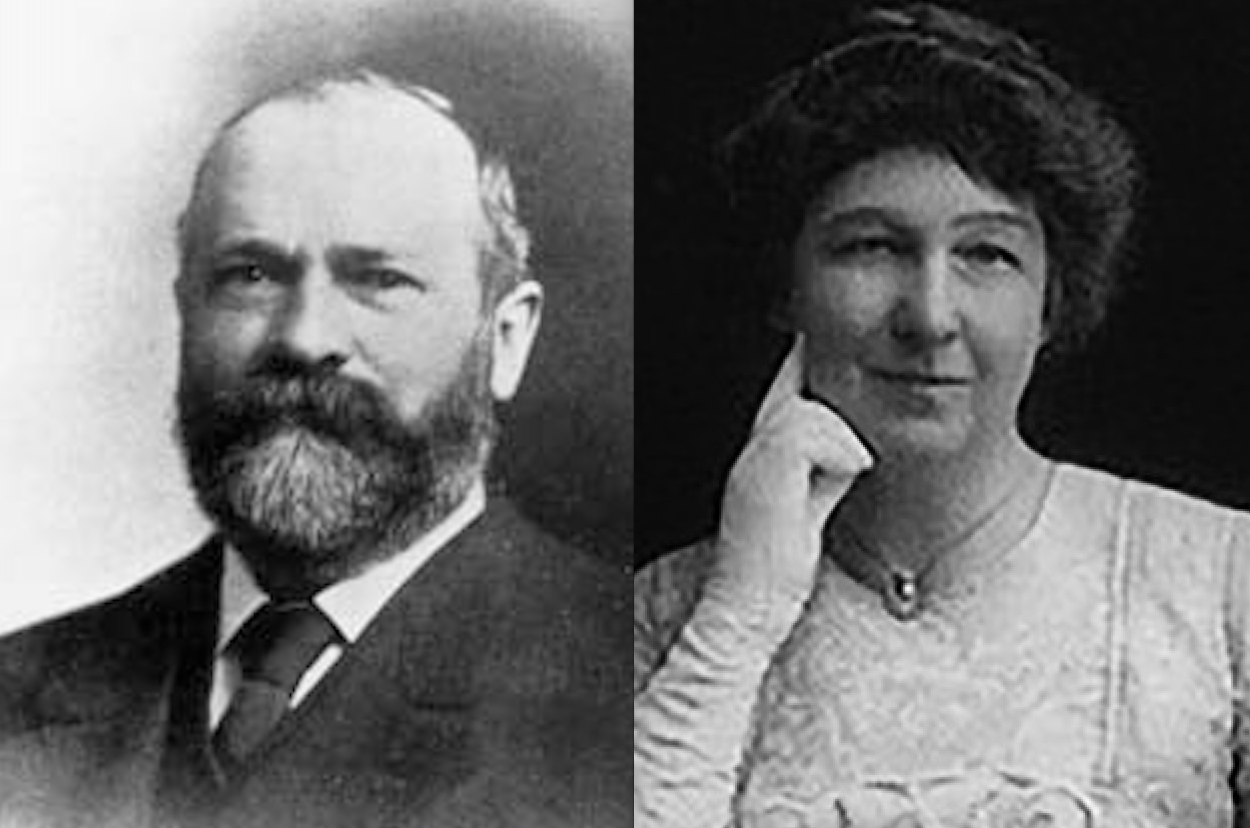

At age 22, she met Frederick Hastings Rindge, the only surviving member of a well-to-do family from Cambridge, Mass. He believed the world was a beautiful place — just waiting to be conquered.

“They saw in each other what the other was missing,” says Randall.

In 1887, Frederick Hastings Rindge and Rhoda May Knight Rindge were married less than one week after they met. Photo courtesy of Malibu Historical Society.

Rindge and Knight were married in less than a week. Not long after, they moved to Southern California. In 1887, LA was changing fast — thanks to gilded age men like Frederick Rindge, who invested old money in the new city. Rindge made money in Los Angeles and then went looking for new worlds to conquer.

In 1892, he purchased Rancho Malibu Topanga Sequit — one of the last of Southern California’s untouched Spanish ranchos. It had been uncontested Chumash land for centuries, with a coastal village called Humaliwo, later changed to Malibu.

The sun sets over Malibu Lagoon, November 2021. Photo by Mike Schlitt.

The property was available because it was isolated and dangerous. There were snakes, bears, mountain lions, and constant wildfires and mudslides. Randall says that naturalist John Muir called Malibu “the most treacherous place he’d ever seen.”

Frederick Rindge paid $133,000 for the property (just over $4 million today adjusted for inflation). His new neighbors — about 60 homesteaders living in the canyons above his estate — were settlers staking claims to government land.

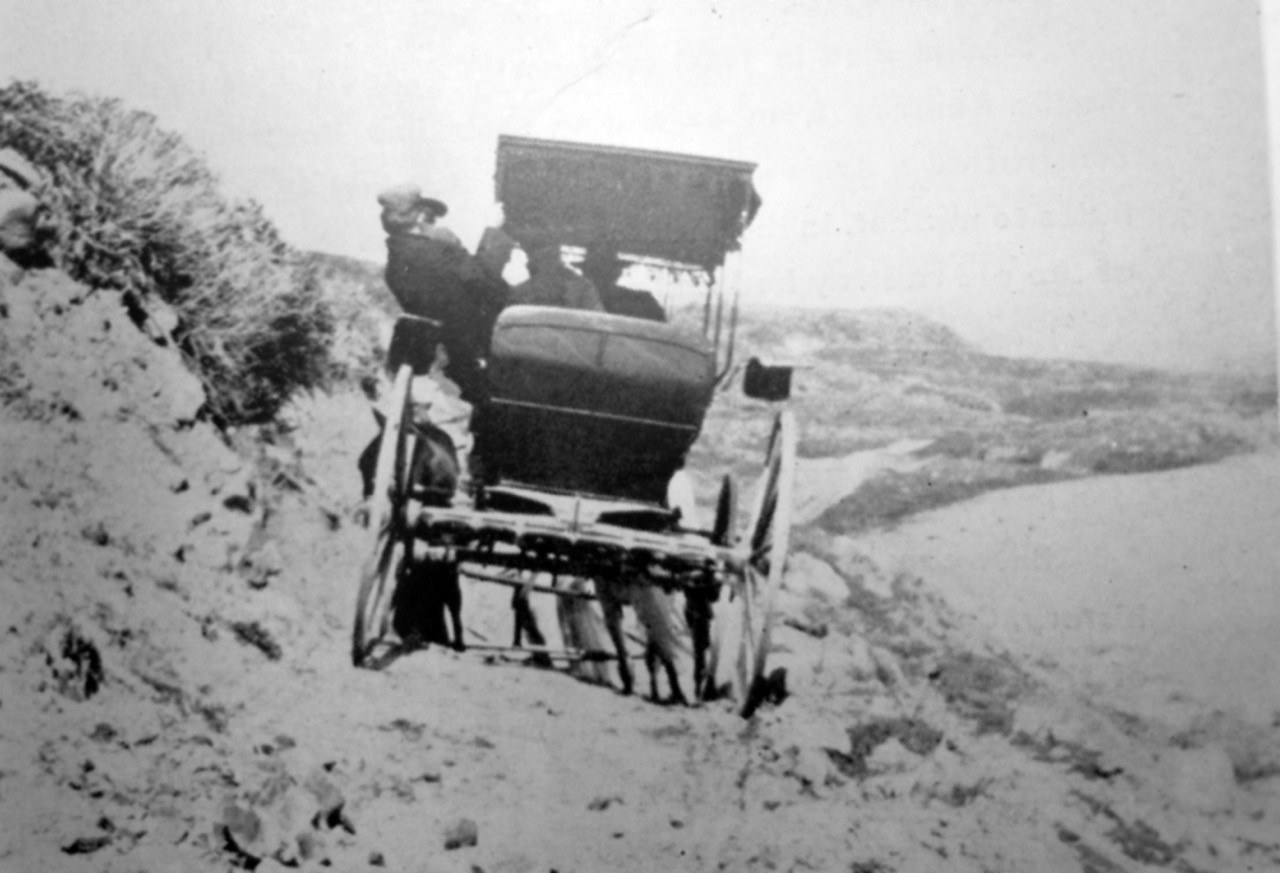

At the time, the only way in or out of Malibu was a series of steep canyon trails or makeshift beach roads accessible only at low tide.

Getting in and out of Malibu near the turn of the 20th century was time-consuming and treacherous. Locals asked for permission to use the Rindges’ private road instead. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Guldimann Collection.

There was one alternative route — a private dirt road running through Frederick’s property, where the Pacific Coast Highway is today. Rindge let the homesteaders use his private road, but his lawyers warned that if he allowed public access, he might jeopardize his own property rights. So Rindge put up gates blocking entry to his estate, with armed guards — in case natural barriers failed to keep trespassers out. He gave the homesteaders gate keys and advised them not to lose them.

“The homesteaders hate this,” author David Randall explains. “The wide open west that they still think they live in is getting smaller and smaller. And it’s also their lifeline.”

Years of lawsuits and escalating tensions followed — the battle over access to Malibu had officially begun. And then in the fall of 1905, tragedy struck: While vacationing in California Gold Country, Frederick collapsed suddenly and died. He was just 47.

With Frederick gone, May’s enemies moved in for the kill.

“Homesteaders laid in wait to try to kill her multiple times,” says Randall. “She had to have armed guards patrolling Malibu and told them, ‘We don't fire warning shots here.’ It really was a kingdom to itself, and people try to kill the queen.”

May Rindge vs. Southern Pacific Railroad

The homesteaders weren’t May Rindge’s only problem. Southern Pacific Railroad wanted to build a coastal route from Santa Monica to Santa Barbara — a route that would cut right through her land.

But May Rindge vowed never to let anyone take Malibu away. It became a symbol of her love for her husband. Why not spend what remained of his fortune to preserve his memory?

May Rindge decided to build her own railroad — a railroad to nowhere.

“It’s right on the beach, and starts getting washed away very quickly,” David Randall explains. “The engineers say, ‘We have to fix this, we have to move it somewhere else.’ And she says, ‘No keep building it.’"

It looked like the grieving widow might be cracking under the pressure. But in fact, her lawyers had found an obscure Interstate Commerce law: If one railway runs through the property, there couldn’t be another one doing the same thing.

“All it was meant to do was to keep the more powerful railroad companies from coming in,” Randall explains.

Completed in 1908, with tracks stretching from Los Flores Canyon (the eastern point) to Yerba Buena Canyon (the western point). The Rindges’ ‘Hueneme, Malibu and Port Los Angeles Railway’ was used to move supplies around the ranch and ship goods from the Malibu wharf. Its chief purpose was to keep the Southern Pacific Railroad company from gaining right-of-way access to the Rindges’ estate. Photo courtesy of Pepperdine Libraries Digital Collection.

Southern Pacific Railroad had to run their new line through the San Fernando Valley instead of Malibu. May Rindge had scored a major victory over one of the most powerful corporations in the country.

A picnic in Malibu

But the march of progress is relentless — and railroads would soon be the least of May Rindge’s problems. In 1908, Henry Ford’s new Model T would give Southern Californians a powerful sense of freedom previously unimaginable, says David Randall. Forget railroad tracks — suddenly there was a powerful constituency for roads.

“For people whose entire lives had been dictated by train schedules, suddenly you could go wherever you wanted in a car at whatever time. [It] could take you right along the coast through this beautiful land, and you didn't have to walk and you didn’t have to be on horseback.”

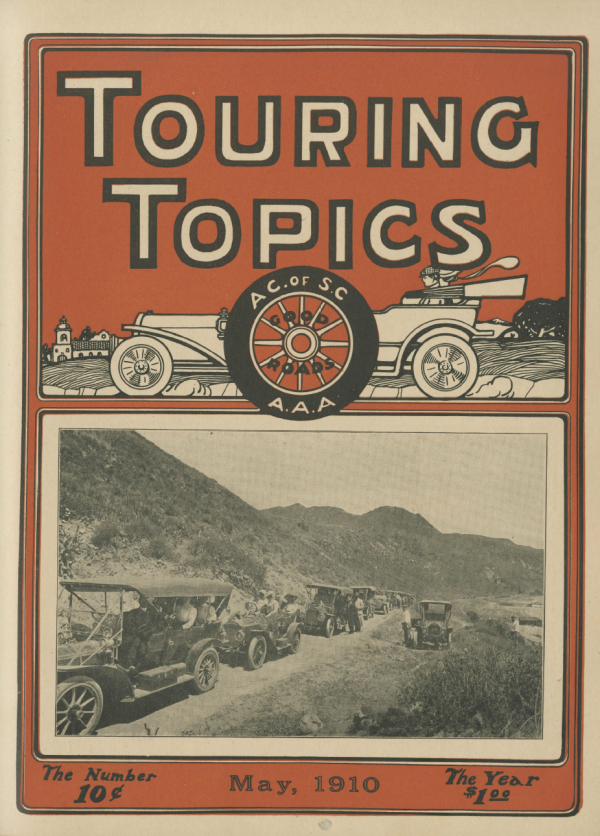

In 1910, the Auto Club of Southern California (AAA) was looking for ways to boost membership. They decided to stage a picnic on May Rindge’s Malibu ranch. More than 200 automobiles and about 1,500 participants drove from downtown to Malibu. Rindge had granted them permission for the picnic, so on this day — unlike all others — the gates were open and inviting.

Why did Rindge let them in? She was an ardent automobile enthusiast, but still, she must’ve seen the danger.

“She had just defeated the railroad, maybe she was feeling pretty confident,” says Malibu writer and artist Suzanne Guldimann. “On the other hand, she lived to regret having that party. It was the first beach traffic jam in Malibu's history.”

In 1909, the Automobile Club of Southern California began publishing its member magazine, “Touring Topics,” which became “Westways” in 1933. This “Touring Topics” edition from May 1910 features a cover story on the Club’s “Malibu Run,” and hailed the event an “unqualified success.” Photo courtesy of Auto Club of Southern California Archives.

The Auto Club of Southern California’s primary mission at the time was to advocate for the building of roads. When Angelenos got their first taste of Malibu’s unspoiled beauty, the city’s movers and shakers (many of whom had attended the picnic) began to demand coastal access for the public.

The following year, 1911, California state engineers began surveying Rindge’s property as they prepared to build an $18 million coastal highway running from Oregon to San Diego, Calif. Rindge sued the state of California. The state sued her back.

More suits and countersuits followed. Los Angeles County, the cities of Venice and Santa Monica, and the U.S. Department of the Interior all wanted public roads on Rindge’s land.

Her lawyers argued that a coastal highway through Malibu would serve no public purpose, and the California State Supreme Court agreed. They ruled against new roads in Malibu. It looked like Rindge might defeat the march of progress after all.

The courts decide

But then in 1923, the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court. Government lawyers — advocating in favor of public roads — decided to try a new argument.

“It was the only argument left and it was actually the most powerful one,” Randall says. They argued that “a road is not just a means of conveyance. It’s also a way to transport yourself by exposing you to something beautiful. If you expose somebody to beautiful things, they're going to improve as a person.”

This was a re-imagining of the whole notion of public good. And where a public good is served, the government can claim private land by eminent domain. The United States Supreme Court was persuaded, and Rindge lost her battle against the road builders once and for all. Suddenly, all those things that made May Rindge fall in love with Malibu became the reason she had to share it with the world.

“It was a kingdom away from everything else,” Randall explains. “And that was so enticing that legally they said that shouldn't be the dominion of just one person.”

Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1923, construction begins on the State Highway near the beach in eastern Malibu. This paved road would be completed in 1929 as the Roosevelt Highway, linking Santa Monica and Ventura, as well as Mexico and Canada. This photo was taken just inside the Rancho Malibu, near Las Flores Canyon, present home of Duke's restaurant. Photo courtesy of Pepperdine Libraries Digital Collection.

In 1929, the Malibu leg of the Roosevelt Highway — it wouldn’t be called Pacific Coast Highway for another 12 years — finally opened to the public.

A sign for Malibu — and its “12 miles of scenic beauty” — is seen along Pacific Coast Highway. Photo by Mike Schlitt.

It was a bitter defeat for May Rindge. Her fortune gone after decades in court, she had to sell off most of her Malibu property. By the time she died in 1941, she’d lost everything.

But in sense, she also won.

May Rindge visits the Adamson House, 1930s. The house was built in 1929 for her daughter, Rhoda Rindge Adamson and her husband. It’s been called the “Taj Mahal of Tile,” due to its extensive use of ceramic tiles created by Rufus Keeler of Malibu Potteries. It was designated a California Historical Landmark and is still standing today. Photo courtesy of Adamson House Archives.

If it weren’t for May Rindge, we wouldn’t know Malibu as it is today. David Randall says, “If Frederick had lived, it would be much more developed. He even drew up plans for a marina.” Instead, May Rindge’s long battle to keep Malibu as it had been when he was alive continues to inspire residents today.

“May Rindge has a posse,” Guldimann says. “Her spirit is alive in every ornery, determined, passionate person fighting to save what’s special about this place [Malibu].”

Adamson House overlooks Surfrider Beach, November 2021. Photo by Mike Schlitt.

This is part of Greater LA’s series on local streets — how they got their names and what they say about past and present life here.