The logistics industry – the business of hauling and especially storing all the goods people buy – has been the economic engine of the Inland Empire for years. Warehouses have sprouted in the open spaces of Riverside and San Bernardino counties like the orange groves and crops they’ve since replaced. But lately, there’s a rattle in the humming motor of that economic engine.

Local cities are pushing back, with some establishing moratoriums on new developments. And there’s been a cool-down in online buying since the height of the pandemic. Amazon, one of the Inland Empire’s largest employers, is recalibrating its warehouse plans after seeing a dent in its bottom line.

After decades of expansion across the region, has the Inland Empire’s logistics sector finally reached its peak?

An aerial view shows the industrial core of downtown Rancho Cucamonga, San Bernardino County, California. Photo by Shutterstock.

In the mid-1970s there were around 160 warehouses in the Inland Empire. “Now there are, in both counties combined, I think 4,300,” says University of Redlands Economics Professor Johannes Moenius. “The square footage has now reached a billion. That is 37 square miles.”

And that still isn’t enough to house, sort, pick, and pack all the stuff we buy.

In one of the few remaining agricultural areas of Ontario, immediately north of the Chino Airport, Amazon’s biggest warehouse on the planet is taking shape in what was once a feedlot. When it’s finished in 2024, the hulking five-story facility will total more than 4 million square feet. Despite its spaciousness, the company estimates it’ll employ fewer than 2,000 people – robots will be doing a lot of the work.

The Amazon mega-warehouse in Ontario dwarfs the surrounding landscape still dotted with dairies and farms. Photo by Matt Guilhem / KCRW.

And yet, even as Amazon prepares to open this monolith, the company is feeling a post-pandemic cool-down. We’re not ordering stuff online the way we did during lockdowns, and Amazon has seen quarterly losses this year for the first time in the better part of a decade. In response, it’s pausing or closing around 50 warehouses nationwide – three in Southern California.

Despite this online buying bump in the road, the Inland Empire will remain a warehouse hub for years to come.

Some 40% of all the goods that enter the U.S. by container come through the Ports of LA and Long Beach. With ready access to freeways, trains, and airports, the Inland Empire has become the staging area for getting all that stuff to where it needs to go.

COVID ratcheted the sector into high gear and underscored how crucial goods movement is.

“It increased our need for logistics,” says Paul Granillo, the head of the Inland Empire Economic Partnership. “Things that before the pandemic we weren’t having delivered – food. You know, you can get your pharmaceuticals delivered. Darn if you can’t get your liquor delivered to your door, right? All things that really weren’t ‘a thing’ that now we’ve just become accustomed to.”

Even so, the head of UC Riverside’s Center for Economic Forecasting and Development, Chris Thornberg, uses two words to sum up Amazon’s COVID-era expansion: “incredibly aggressive.”

“A lot of folks were like, ‘Does this make sense? Do you really think you’re going to corner the industrial market completely, Jeff [Bezos]?’”

He says the logistics boom of the last couple years is behind a rash of moratoriums on new industrial developments cropping up around the Inland Empire. Cities including Pomona, Chino, Redlands, Norco, and Colton have all passed ordinances to temporarily pause the sector in order to study the impacts of warehouses.

“I think it was that surge that really got local folks motivated to start pushing back hard,” says Thornberg. “They rightly, of course, anticipated another huge surge in investment in the area and a lot of folks just didn’t want to see that.”

Colton was among the cities to act early, passing a moratorium on new industrial developments in spring of 2021. The hardscrabble town is home to a nexus of railroad tracks and sits right along the 10 freeway, so it’s perfectly situated to appeal to the logistics industry.

During the freeze, the city is hoping to remedy some zoning issues, study truck routes to make them less disruptive, and hone its negotiating skills so future projects come with more public benefits. Even with the changes, Colton already has approximately 3 million square feet of distribution centers standing. Remaining space is limited.

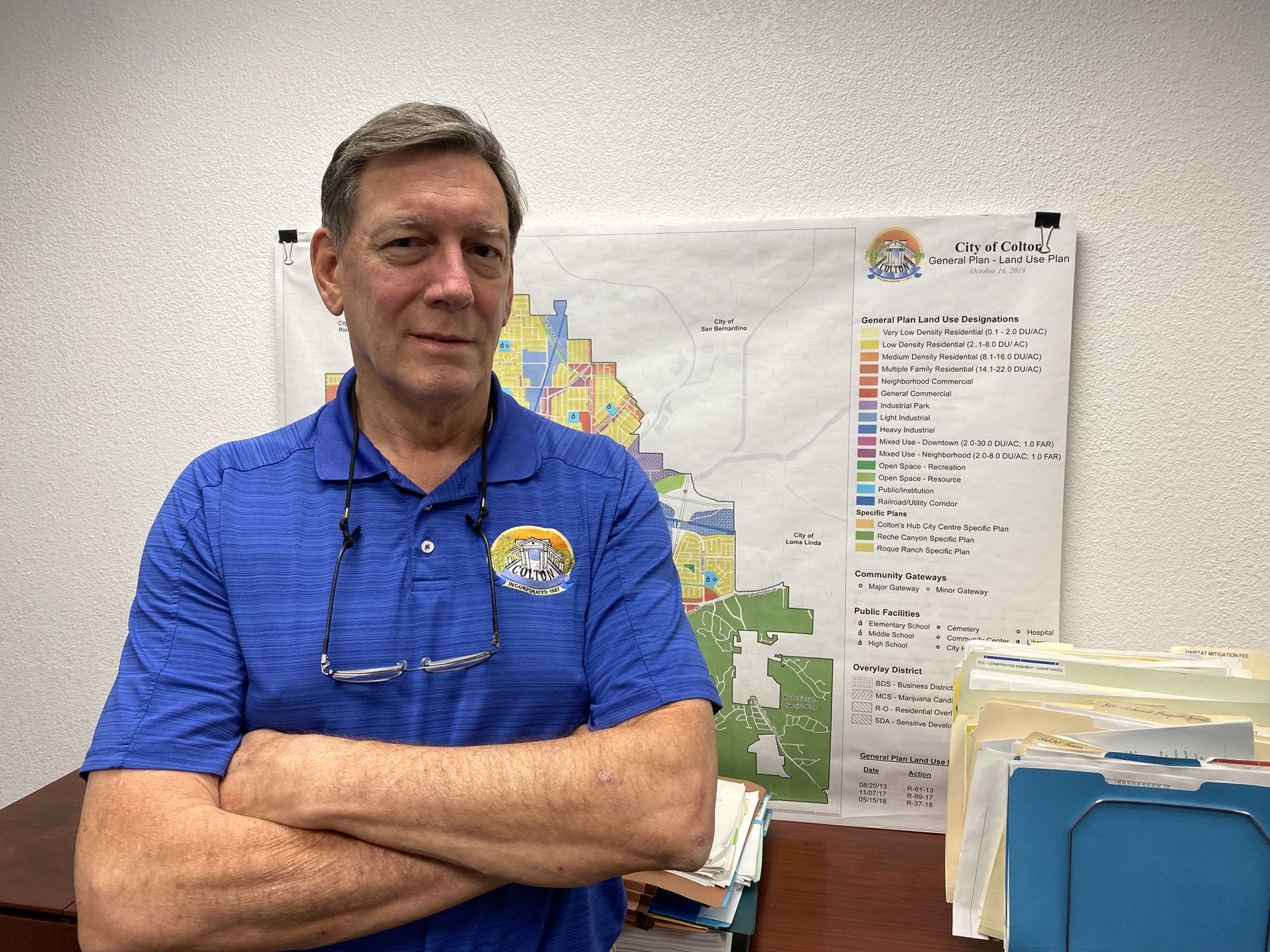

“Most of our industrial areas are built out,” says Mark Tomich, Colton’s development services director.

But wait, there’s more.

“Large logistics facilities often don’t pay their way because they don’t typically generate sales tax, only property tax,” Tomich says. “And then they don’t necessarily contribute greatly to local spending because of the limited number of employees.”

To review: Colton is mostly built out, warehouses aren’t major revenue generators, and they don’t require that many workers. Odds are good you’re coming to the same conclusion as the man overseeing the city’s planning and development departments.

“Logistics can’t really be the backbone of our economy,” says Tomich. “The wages aren’t there – and not that many employees. So, I don’t think in the long term that that type of industry is a positive for this region.”

Colton Development Services Director Mark Tomich points to Colton’s long history – it incorporated in 1887 – as contributing to its reevaluation of warehouses. Zoning in the past wasn’t regulated like today, and some parts of the city feature industrial areas next to residential ones. Photo by Matt Guilhem / KCRW.

Although Colton and a handful of other towns are individually taking a hard look at warehouses, logistics is a regional juggernaut, so one city’s rejection may be another town’s opportunity.

“For us to have this conversation city by city by city really doesn’t get to the regional strategy of: How do we make sure this is benefitting all of us?” says the head of the Warehouse Workers Resource Center, Sheheryar Kaoosji. “Because if they don’t build the warehouse in Colton, they’ll build it in San Bernardino. If they don’t build it in San Bernardino, they’ll build it in Rialto. It’s probably the same freeway exit, right?”

No matter what happens, Kaoosji thinks the sector is here to stay and will remain a dominant force. Let’s be honest – we’re going to keep clicking “buy now.”

So, have we hit peak warehouse?

“For the Inland Empire, it may well be peak warehouse,” says University of Redlands Economics Professor Johannes Moenius. “Not tomorrow, not the day after tomorrow, but if there are no fundamental changes, five years from now it might be game over.”

But that doesn’t mean the logistics industry overall is expected to slump. Just last month Kern County gave the green light to an inland port. The facility in Mojave will operate around the clock with trains and trucks. Most of the best locations for the sector in suburban Southern California have been built out, but open tracts of desert are beckoning builders.