On August 10, 1936, the land we now know as Joshua Tree National Park was officially deemed a national monument. That came after years of crusading by Pasadena resident Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. Getting more than 800,000 acres of land preserved was no small feat, but her name remains little known compared to other conservationists of her time, like John Muir.

Born in 1866 in Mississippi, Hoyt grew up on a cotton plantation — a privileged home surrounded by politics. Her father fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War, then after the war became a state senator. She was sent to finishing (etiquette) and music schools to learn the important skills of the time, like table setting and piano playing, then met Sherman Hoyt, a doctor. They married and eventually moved west to Pasadena in the late 1890s, settling on five acres in South Pasadena.

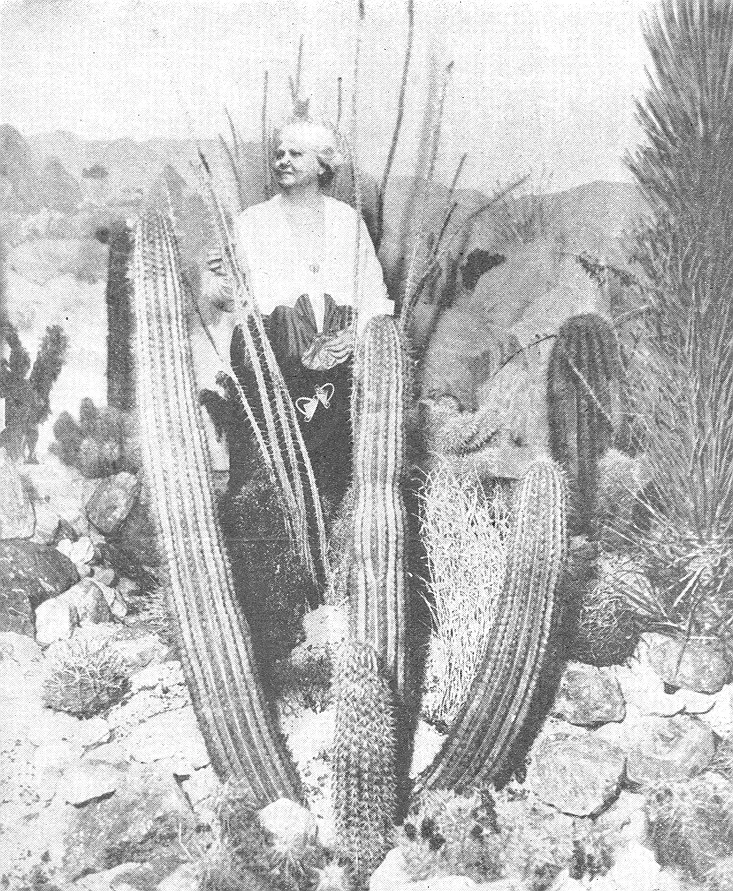

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt used her political savviness and southern etiquette school skills when fighting for desert preservation. Photo courtesy of Joshua Tree National Park Archive.

Not long after landing in Pasadena, Hoyt lost a son in infancy and then her husband.

In her grief, her focus, which had always been civic-minded (president of the Boys and Girls Club, member of the Valley Hunt Club, president of the LA Symphony Orchestra), turned towards gardening and especially the native plants of her new home state. (She did stock a pond in her garden with alligators, though, just to bring a little bit of Mississippi to California.)

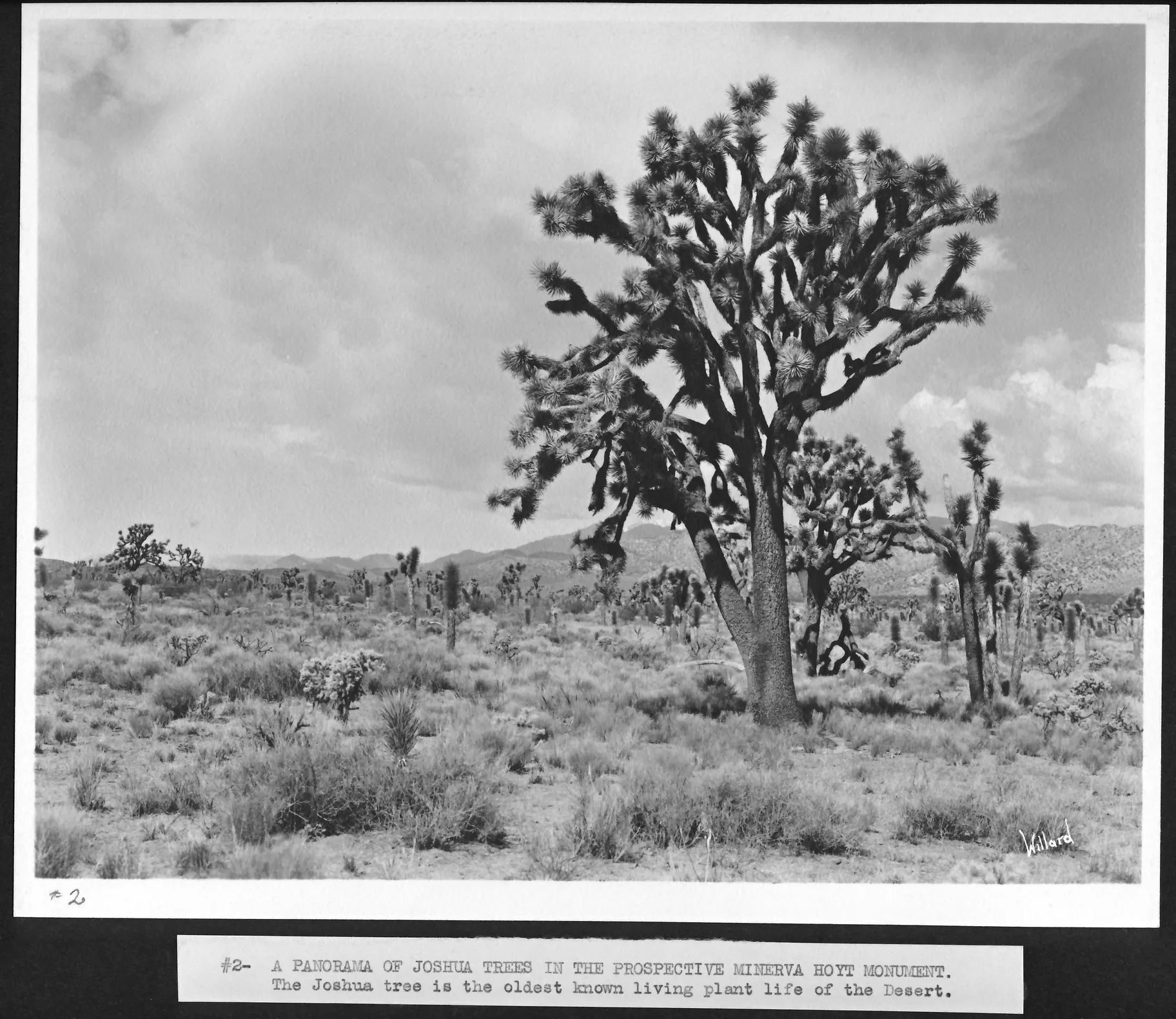

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt advocated to preserve an area comprising scenic granite boulder formations and millions of Joshua trees found in the Little San Bernardino Mountains north of Palm Springs. Photo courtesy of Joshua Tree National Park Archive.

“During nights in the open, lying in a snug sleeping-bag, I soon learned the charm of a Joshua Forest. This desert … possessed me, and I constantly wished that I might find some way to preserve its natural beauty.”-Minerva Hamilton Hoyt, 1931

Retired Joshua Tree National Park ranger Joe Zarki has been studying Minerva since he arrived at the park in 1995. He says of her early desert days, when she was in her 60s, “At this stage of her life, she decides, ‘I'm going to spend my years working on desert conservation.’ And boy did she.”

This was where her southern hospitality and political know-how came into play — as she figured out the best ways to lobby powerbrokers to preserve a desert she saw being treated like a wasteland, rather than the rich ecosystem that it was. She began with education, sending railcars full of desert plants across the country to Garden Club of America shows. Designed with her neighbor, O.W. Howard, these elaborate displays featured painted backdrops, taxidermied animals, and live plants from the desert. The creations brought the desert to the East Coast, where authority figures made decisions about what land to preserve. The shows were so popular that she was invited to send one of her desert exhibits to Kew Gardens in London, drawing international attention to her cause.

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt poses in one of the desert landscape exhibits that she shipped all over the world. Photo courtesy of Joshua Tree National Park Archive.

Back in America, she used her Pasadena political connections to bang the drum for the desert, but didn’t make real progress until Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected in the 1930s.

“She makes a trip to Washington D.C., meets Roosevelt. He introduces her to Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior. Now, Roosevelt likes what he's hearing from Minerva,” says Zarki.

So Roosevelt sent men to scout the desert — to see if it was worth making a national park with the land she was making a fuss about. They were ultimately unimpressed.

Still, Hoyt was undeterred and kept pestering Ickes, who ultimately assigned the same scouting task to Harold Bryant, a Berekely grad, who understood the desert and supported her vision.

And after more than a decade of crusading for the desert, in 1936, Joshua Tree National Monument was finally founded.

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt’s desert exhibit from 1928 was shipped by refrigerated car to New York City, where it was displayed in The Grand Central Palace. Some flowers were even flown in daily to ensure freshness. Photo courtesy of Joshua Tree National Park Archive.

Minerva spent the rest of her days lobbying for it to become a national park, but that wouldn’t happen until 1994. Joe Zarki was behind the move to have a peak in the park named after her in 2013.

“One of my reasons for wanting to focus on Minerva is just that I realized we still need her today,” Zarki says. “My hope is that her story would inspire people today, particularly young women today, to take up the cause. Because we need more young people involved in conservation.”