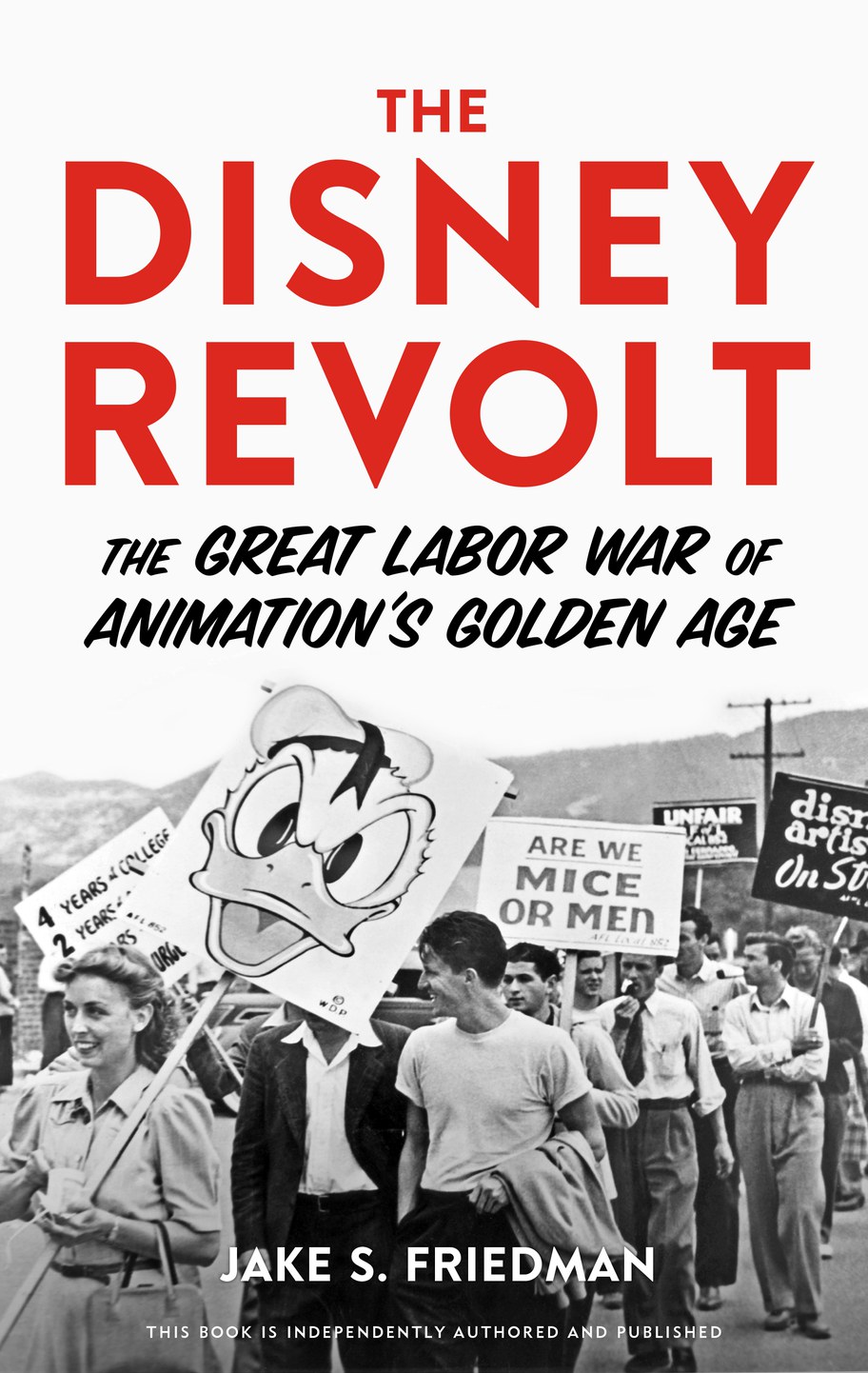

Hundreds of animators, colorists, background painters, and more walked out of Walt Disney Studios during summer 1941. At the time, enthusiasm for union organizing ran rampant across the country, and Disney’s animation production line demanded fair wages for their work, as well as overtime. The famous strike changed Disney animation forever.

The lead organizer behind unionizing was animator Art Babbitt, an influential part of the early Disney creative team, says animation historian and writer Jake S. Friedman. He chronicles the five-week strike in his latest book, “The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor War of Animation's Golden Age.”

“He played such a pivotal role in the artistry of animation and raising Disney Animation up. He's responsible for so much, even before the famous nine old men,” Friedman explains. “If you look at the old photos of [Walt] Disney with his crew, Art Babbitt is always in there. He rose to a very high status in Walt's inner circle relatively quickly.”

Friedman says Babbitt was instrumental in establishing art education classes at Disney for animators to hone their skills, and is credited for developing the character of Goofy.

But Friedman says that it wasn’t until working on his book that he truly learned who Babbitt was. With the help of an old NYU professor and Babbitt's widow Barbara Perry, he immersed himself into the history.

Jake S. Friedman began “The Disney Revolt” in 2006 with a push from his former professor. Photo courtesy of Chicago Review Press

Much of the trouble at Disney started after Snow White was released in 1938. Prior to the film’s release, Friedman says Disney animators, artists, and management (including Walt Disney), were all loyal to one another.

“Up to the making of Snow White and its premiere, everyone was in it together. ‘All for one, one for all. If we go down, we go down together.’ They were promised these overtime bonuses. They were promised the extra time that they were spending,” he explains.

All of a sudden, Walt Disney removed himself from staff, the bonus plan disappeared, and focus turned to moving the studio from LA to Burbank.

“The artists and the population of the Disney Studio split down the middle. Some were super loyal and shared Walt's vision of making art and the others were like, ‘Wait, this is still my job, I have a family to raise. I have mortgages to pay. I can't do that with admission to a new studio. I need the money that I was promised.’”

Despite the difference in opinion between Disney management and its workers, Friedman says Walt was no villain in the story.

“If you're looking for a good versus evil story, my book is not it. It's about two very passionate, very stubborn human beings, Walt Disney and Art Babbitt, who are really fighting for what they believed in, but grew increasingly polarized due to external circumstances.”

Author Jake S. Friedman wrote “Disney Revolt” in part to highlight often overlooked animator Art Babbitt, one of the leaders of the union movement at Disney. Photo by Kenneth Gronquist.

Friedman says the Disney unionization is an example of a group of workers who were dedicated to fighting for their rights.

“They stood up for what they believed in. They went all out with their decorated picket signs and their decorated flyers. And Art Babbitt went out and contacted this studio and that studio, and the press, and everyone worked so hard to get what they wanted. These are people who were not loafers, and they weren't what the studio called deadwood. They were people who wanted their fair shake at it.”