LA is famed for its architecturally inventive hillside homes, but perhaps the most iconic are those that jut out from the edge of mountain ridges over canyons. Stilt, or platform, houses are simple in concept – essentially boxes on slender, cross-braced columns – but hugely dramatic as they cantilever out over a precipitous drop. In the post-war years around 1,500 were built when they were a relatively affordable solution to building on very steep sites. For residents without a fear of heights, they offer a wondrous perch above the city.

Their bravado and seeming perilousness has also made them movie stars, typically portrayed as the home of a troubled soul – a drug dealer (“Lethal Weapon 2”) or a gambling addict (“The Gambler”) or a peeping Tom (“Body Double”). Or they serve as a strong visual in a disaster movie as they collapse down the hill; think “Earthquake.” Sometimes they are the fictional home of a good guy in a world of bad: Hieronymus "Harry" Bosch, the LAPD homicide detective in Michael Connelly’s long running crime series, occupies a stilt house in the Hollywood Hills, which he was able to buy after selling a script based on one of his successful cases. Only in LA! From his deck he can eye the bright lights of the noirish city, while thugs creeping up from underneath are a routine threat. For the TV adaptation “Bosch,” producers used a 1959 house on Blue Heights Drive, designed by Frank L. Stiff.

Or there is the stilt house in “Heat,” occupied by Trejo (Danny Trejo), the “good guy” getaway driver for Neil McCauley’s (Robert De Niro) band of thieves. The “Heat house,” incidentally, went on the market this year with much fanfare.

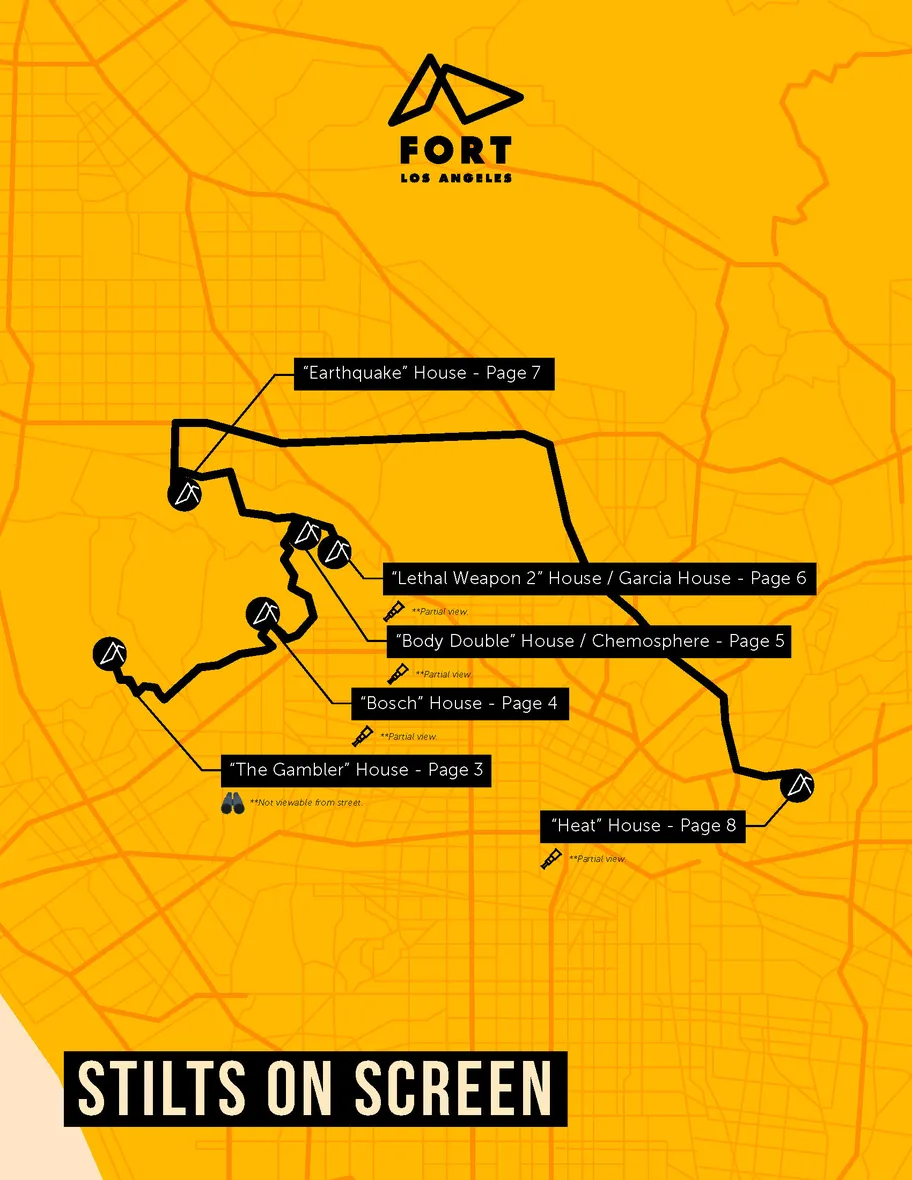

Now the nonprofit Friends of Residential Treasures: Los Angeles (FORT: LA), headed up by filmmaker Russell Brown, has created a free downloadable self-guided trail map of six of the “Stilts on Screen.”

The movies featuring stilt houses seem to suggest that people who live in them have a death wish, says Brown. A visit to some of these homes, however, tests those with vertigo, but reveals that they are treasured by homeowners who view them as much less menacing – and far more peaceful – than Hollywood might lead you to believe.

“I think Hollywood is using these films for a very specific purpose,” reflects Brown. “But the reality is: A lot of people really love living here and have really warm emotional reactions to being here. So I don't know if the movies have totally gotten it right.”

In real life, the stilt-house-building trend was short-lived. It turned out that fire licking up from below could be a problem, and in 1966 new building codes for fireproofing made them prohibitively expensive to build. Then 13 stilt houses collapsed in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, causing three fatalities. Experts found that the stilt houses whose floor beams were not attached to foundations were vulnerable. When the stilts and cross bracing systems faltered, the floors slid forward and down the slopes. Existing stilt houses have been strengthened where necessary.

Hillside builders today either grade the land or create thick walls that extend right down to the ground, flattening the slopes or filling them with fortified structures that crowd out the flora and fauna of the hills.

Designed by John Lautner and held up by slender columns, this house was fit for evil in Richard Donner’s classic cop caper, “Lethal Weapon 2.” Photo by Amy Ta.

Looking up at the Garcia House on Mulholland Drive, one the grandest of LA’s stilt houses, designed in 1962 by the architect John Lautner, you see stork-thin, slanting legs seemingly holding up an immense and stunning house, with an eyelid-shaped parabolic roof over stained glass windows. Those 60 feet columns are buried deep into the hillside.

The Garcia House was originally built for American composer Russell Garcia. Actor Vincent Gallo later owned it, and then a DreamWorks executive. On celluloid, it played the den of evil for the racist South African drug smuggler Arjen Rudd (Joss Ackland) in the film “Lethal Weapon 2,” chased down by homicide detective Roger Murtaugh (Danny Glover) and narcotics officer Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson).

One nearby stilt house has lived out the darkest possibility for these homes on film, when it collapsed on screen in the 1974 disaster film, “Earthquake.” In the film the house nearly crushes Denise Marshall (Geneviève Bujold) when a 9.9 magnitude quake strikes while she is taking her morning stroll.

What was destroyed in the film was actually a model. The house itself is still standing on Alta Mesa Drive in Studio City. The film won a special Oscar for visual effects, and the same shot was actually repurposed for an episode of “The Incredible Hulk.” Brown says, “So this stilt house has died multiple times on screen.”

Lorraine Jonsson’s stilt home in the Stone Fisher development in Sherman Oaks offers a spectacular view of the canyon. Photo by Amy Ta.

At the Stone-Fisher Speculative Platform Houses complex in Sherman Oaks, some 17 cliff-hanging houses leave the hillside barely touched. They were originally designed by the important modernist architect Richard Neutra, in collaboration with the structural engineer Arthur H. Levin, who wrote the book on hillside construction. According to Neutra’s son Dion, also an architect, there was a dispute with the developer about financial issues and the quality of construction, so another architect, William S. Beckett, completed the buildings and is credited for them. Unfortunately, Neutra’s early concerns may have been justified: Three of the houses broke from the street in the Northridge earthquake and a 4-year-old girl died. Since then, the houses have been tested and reinforced.

“I love good architecture. I love nature. I love light. I love the unexpected. And I love the unusual. So I get all of that here,” says Lorraine Jonsson. Photo by Amy Ta.

Lorraine Jonsson initially leased her home in that Sherman Oaks complex, and then, feeling totally stable and safe in the structure, she bought it. Her space features much of its original design: a free-flowing kitchen, plus dining and living room with windows on three sides, leading to a deck with a deep drop and a spectacular view. Even though it is in the hot San Fernando Valley, the home is filled with cooling breezes and the rustle of trees outside.

“I love good architecture. I love nature. I love light. I love the unexpected. And I love the unusual. So I get all of that here,” says Jonsson.

Michelle Johnson’s stilt house has been remodeled – and now has a black metal exterior – but remains true to the Neutra’s original concept of barely touching the land. Photo by Amy Ta.

In the same complex, homeowner Michelle Johnson says she and her family moved recently from Minnesota to Los Angeles. A self-described “farm girl,” she sought out a home that would have a connection to the wild, and found it in her updated stilt home — although the house was remodeled by the previous owner Donald M. Goldstein and is now encased in glass walls. “I wanted something that was interesting. I wanted something that was exceptionally well-made and exceptionally well-maintained. And something that had a great view,” she says.

Floor-to-ceiling glass gives the sense of floating over the landscape in Michelle Johnson’s platform house. Photo by Amy Ta.

Decorative, colorful figurines sit in the dining room of Michelle Johnson. Photo by Amy Ta.

“I wanted something that was interesting. I wanted something that was exceptionally well-made and exceptionally well-maintained. And something that had a great view,” says Michelle Johnson. Photo by Amy Ta.

This map shows a trail of six “Stilts on Screen.” Courtesy of Friends of Residential Treasures: Los Angeles (FORT: LA).

More:

LA Conservancy: Platform houses

LA Conservancy: William S. Beckett

LA Times: Above It All