Lea la versión en español de este artículo aquí.

On the evening of June 6, the tiny chambers of Cudahy City Council buzzed with excitement. Beneath fluorescent lights, residents packed into folding chairs and lined up at the back of the room, eagerly waiting for the meeting to be called to order.

At just over one square mile, Cudahy is one of the smallest cities in LA County, and its council meetings aren’t always this lively. But for months, residents of the 85% renter community had been showing up in droves to demand one thing — tenant protections.

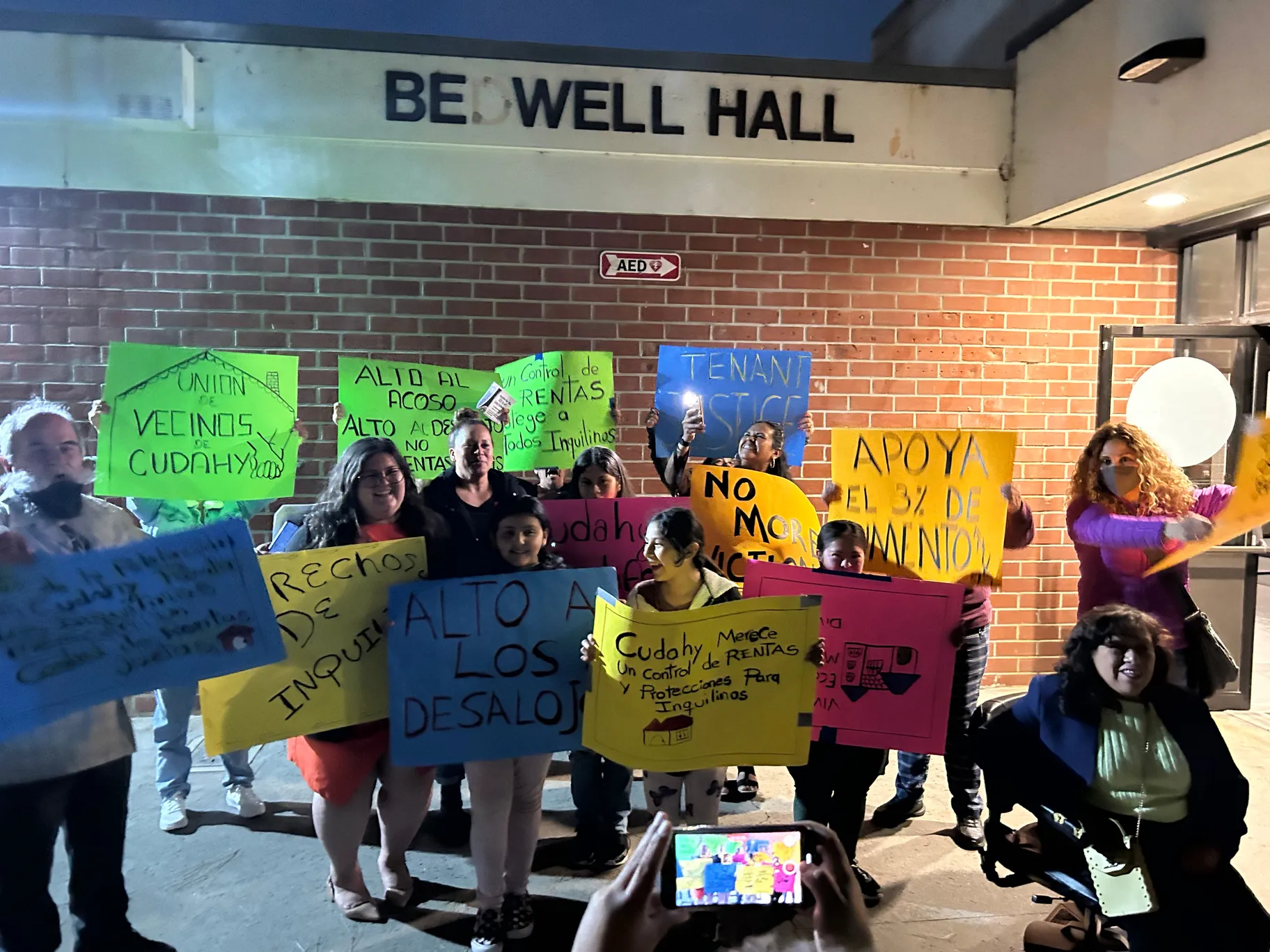

That night, the council was set to do a final reading of two new measures, which would cap annual rent increases at 3% and provide relocation assistance and other safeguards for tenants. And after hours of public comment and a final vote, both passed unanimously. The crowd burst into applause.

The new laws make Cudahy the latest city in Southeast LA to pass rent control, following in the footsteps of its neighboring city Bell Gardens. It’s part of an ongoing push to protect renters from large rent hikes and displacement in the region — a push spearheaded by a group of women, who see controlling the cost of housing as the key to protecting their families’ futures.

Cudahy is one of the smallest cities in Los Angeles County. Like many cities in Southeast LA, it did not have any renter protections in place until they were passed earlier this month. Photo by Zoie Matthew.

Fighting for families

Four years earlier in Bell Gardens, the fight for rent control in Southeast Los Angeles was sparked by conversations around a very different topic — family planning.

In 2019, organizers from the nonprofit California Latinas for Reproductive Justice began knocking on doors to ask families about the main issues they faced. And over and over again, they kept hearing the same response.

“Housing was the top priority,” says Martha Pineda, the group’s lead organizer. “Anything around housing, habitability or instability, the lack of good conditions in the housing in Bell Gardens, and then of course, rent increases — either large rent increases, or that the rent was very unaffordable.”

Pineda says while it might seem strange for an organization like theirs to take on local housing policy, the two issues are in fact deeply intertwined.

“For somebody to choose to start a family, sometimes if they can't buy a home, or they can't rent a home on their own, that stops them from having a family,” she says. “If you already are crammed with four kids in one two bedroom, and you want more that impedes your decision, because of your housing conditions.”

Three fourths of Bell Gardens residents are renters. But like the other small cities that make up the patchwork of Southeast LA, it didn’t have any measures in place to stop housing prices from skyrocketing. The only limit on rent increases was the one set by the state – 10% a year.

So, the tenants decided to change that. They started a tenant advocacy group called Union de Vecinas, which was mostly made up of women.

“Women who are moms, single moms, a lot of single moms, tias, grandmas who have become moms yet again. They're all mostly Mexican immigrant working class folks,” says Pineda.

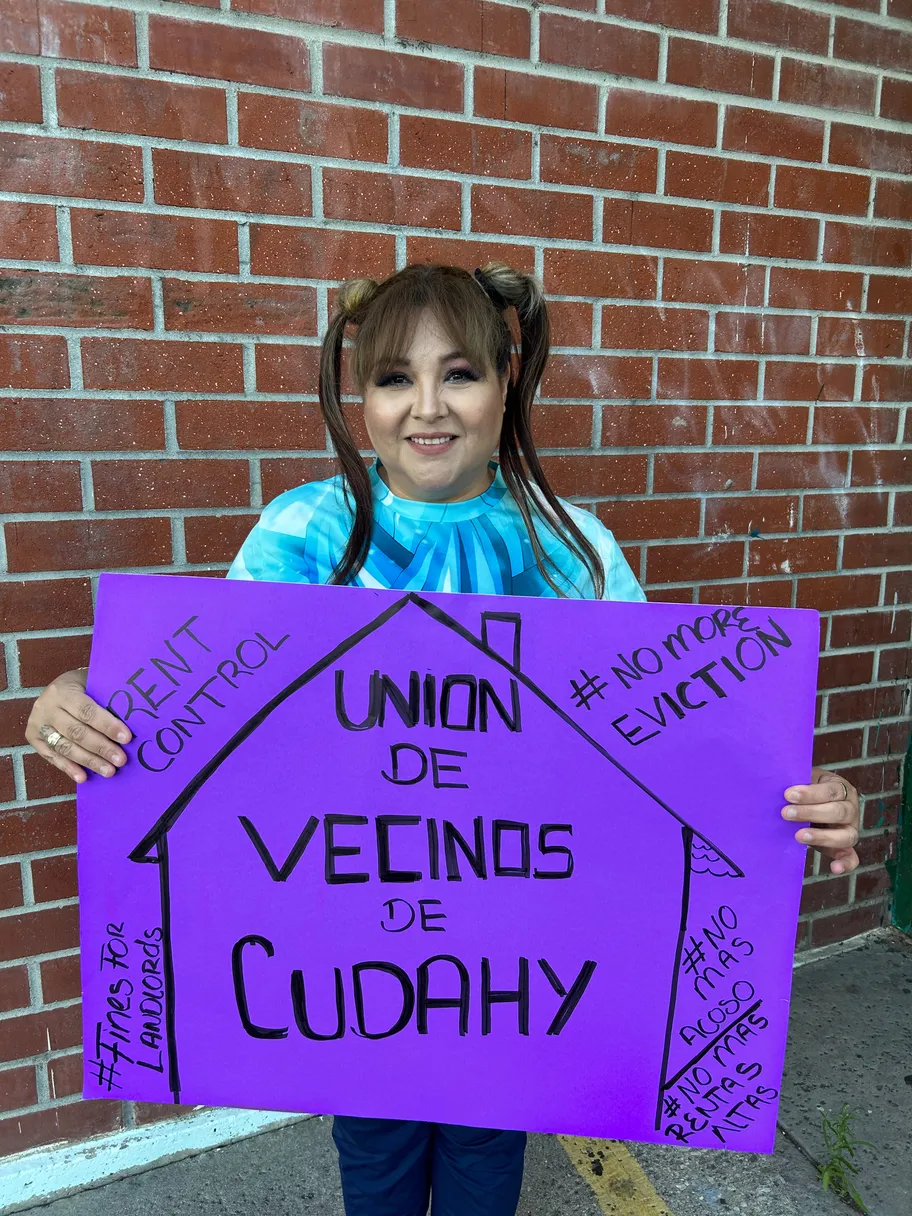

Lucia Veloz began organizing with the Union de Vecinas in Bell Gardens after receiving an illegal 25 percent rent increase. Now she is supporting tenant organizing in other Southeast LA cities. Photo by Zoie Matthew.

Cudahy resident Lucia Veloz got involved after her landlord tried to illegally raise her rent by a whopping 25%. She quickly found that spreading the word about rent control was harder than it might seem.

“It was difficult in the beginning because people didn’t believe,” she says in Spanish. “They didn’t believe that such a thing was possible.”

Veloz and the other tenants spent more than two years “going door to door, going out to demonstrate, collecting signatures, talking to the council over and over and over again,” she says.

And in September of 2022, their efforts paid off, when Bell Gardens became the first city in Southeast LA to pass rent control.

“I couldn’t cry that day because I couldn’t believe something like this had happened,” says Veloz. “I couldn't believe that a small group of just 10 women had achieved something so big.”

The movement spreads

Since their victory, tenants in Bell Gardens have continued to support efforts to implement tenant protections in other Southeast LA cities, including Cudahy, which passed rent control earlier this month, and Maywood, which has been considering a similar policy.

Like Bell Gardens, these cities are dominated by renters. But that doesn’t mean passing protections is a breeze.

“We have never even voted on rent control in Cudahy, this was the very first time,” says Cudahy City Council Member Elizabeth Alcantar, who spearheaded the rent control campaign in her city.

That’s partially because most people in these offices are homeowners, and it isn’t their priority, she says. Sitting on the council is essentially volunteer work in cities this small, and many renters simply don’t have the means to get involved in local politics. Alcantar is one of only two renters currently in office in Cudahy.

“Working class people probably don't have time to file to run for office, to run for office, run a campaign, talk to people, fundraise — do all the things that you need to do in order to get into office to make the change you want to make happen,” she says.

There is also sometimes fear about speaking up in immigrant communities, where tenants might face retaliation or threats from landlords.

“I've spoken to renters who were facing a $700 increase in their rent, and when they pushed back against their landlord and told them, ‘Hey, I don't think this is legal,’ their landlord threatened them with calling immigration,” she says.

And there’s the issue of corruption — which has plagued governments in Southeast LA for decades. Officials in Bell, Cudahy, South Gate, Maywood, and Lynwood have all been involved in high-profile scandals over the years — resulting in a dearth of public trust.

“It's something that kind of looms over us,” says Alcantar. “And that might have been one of the reasons why, again, people-protective policies were not being centered, why they weren't being passed, because it was focused on other issues that frankly should not have been the focus.”

But the success in Bell Gardens galvanized community members to push harder for renter protections. Councilmember Alcantar set up an ad hoc committee on rent control, and the Union de Vecinas came to town.

“They told me Irma, I can get you a megaphone, and we went out on the street to tell people to come out to speak out … and ask for a 3% [cap] and just cause [eviction protections],” Cudahy tenant and committee member Irma Lopez says in spanish.

That has inspired even more mothers, like Cudahy renter Verónica Cervantes, to join the fight.

“I do this thinking of my children because it is for their future” she says. “They also suffer when they see [landlords] arrive and give the letters to their mothers, or yell at the mothers in front of the children.”

Families celebrated outside of the Cudahy city council chambers on June 6, after the passage of the city’s rent control ordinance. Photo by Zoie Matthew.

Other local groups, like East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice (EYCEJ), worked with tenants to form the Communities and Renters Autonomous Collective, which is now pushing for these policies across the region.

“This is where community basically talks about what's happening and strategizes, and our actions right now are looking like showing up to council meetings to give those public comments,” says EYCEJ organizer Jasmine Gonzalez.

The uptick in organizing around tenant protections in small communities like these has raised alarms for some property owners. Dan Yukelson, executive director of the Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles, says they’ve been sending lobbyists to meet with council members, and have tried to get more landlords to show up to meetings.

“Obviously we come out and oppose those types of regulations. But what we're seeing when we're at these meetings, unfortunately, there's a lot more renters out there than there are property owners,” says Yukelson.

Lopez says they don’t plan to stop showing up anytime soon. She hopes to offer the same kind of support she got from the Bell Gardens tenants to other nearby cities fighting for tenant protection measures.

Southeast LA is coming together as a community around rent control, Lopez says, and she wants to see it roll out in communities like Maywood, Lynwood, Huntington Park, South Gate, and beyond.

“I am making a movement for more tenants to raise their voices and ask for it,” she says.