After a year-long COVID closure and then a freak storm in 2021 that washed out part of the road up to the estate, the Central Coast sanctuary of publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst is now celebrating its centennial two years late. The famous attraction is using its 100th anniversary to honor Julia Morgan, California’s first licensed female architect and the woman behind Hearst’s grandiose real estate dream.

“I’m a huge Julia Morgan fan,” visitor Suzanne Miller enthuses. “I grew up seeing the stuff she built in the Bay Area and I had never seen down here, so we just kind of jumped in the car and came down.”

Morgan designed more than 700 projects over the course of her career. In 2014, more than half a century after her death, she was awarded her profession’s highest honor – a Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects.

Suzanne Miller says her first trip to “La Cuesta Encantada” – the enchanted hill, as Hearst formally named his mansion – has sparked a deeper interest in the architect.

“I think it’s kind of interesting how hodge-podge the house is in terms of architecture and art, and that’s what makes me a little more curious about it,” says Miller.

Hearst collected nearly every sort of art or antiquity under the sun, but through a collaboration spanning 28 years, he and Morgan made an estate that integrated his boundless artifacts with a home that was, for its time, thoroughly modern.

Atop the hill where Hearst sited his fabulous home, gazing at a temple lording over the Neptune Pool, you can see architect Julia Morgan’s subtle mastery of blending old and new. She incorporated ancient columns holding up a pediment Neptune resides in, part of Hearst’s collection, with improvised elements of her own design.

An oasis out of ancient times, the Neptune Pool is arguably the most famous location at the castle. The structure guests take in today is the third iteration of the pool completed in 1936. As guides tell visitors, Hearst kept “gaining new vision” for his lido, and Morgan kept making it grander. During Hearst’s time, the expansive 104-foot long pool was gently heated and a favorite with his Hollywood guests. Photo by Matt Guilhem / KCRW.

“This was part of Morgan’s way of working with Hearst,” says tour guide Kathryn Keller, pointing to the structure. “There would be historic elements like the columns there that date back to Roman era, first to fourth century AD, and then fragments of various other Roman buildings up on top. But where you had a gap, you would have the craftsmen step in, cast some nice concrete that would look marble-like, and they could finish out the temple facade.”

As for the 345,000 gallon Neptune Pool, California State Parks’ Dan Falat, who’s along for the tour, advises against “accidentally” falling in. Should you happen to make a splash, you’ve quickly reached the end of your tour.

“They will definitely be taken down the hill in free transportation, issued a citation, and/or depending on how severe it is, it could go further than that,” he says seriously. “We try to dissuade everybody from doing that.”

Julia Morgan was known as a client’s architect. You’d hire her, she’d listen, and turn your vision into a place. One of her challenges at Hearst Castle was a massive fireplace Hearst acquired, for which he wanted an appropriately grand space to house it along with a collection of Flemish tapestries. The assembly room, which Morgan designed around that hulking mantel, is one of many examples of the partnership between Morgan and Hearst. In fact, she described him as the castle’s co-architect, in no small part because they were in constant communication.

“A thousand letters we have in our archives sent between Hearst and Morgan – letters and telegrams, and another 9,000 between their staffs,” Keller says.

Along with frequent correspondence, Morgan also made numerous trips to San Simeon to oversee construction. She didn’t exactly run in the same circles as Hearst’s guests – who included literary, political, and movie stars.

“Julia Morgan was a self-effacing, skinny woman who wore tweed skirts that were inches too long; she wore no makeup,” says Keller as she recalls an observation made by one dinner guest. “And in the dining room, in the evening, ‘she looked like a neat bantam hen next to birds of paradise.’ And yet, she always had the seat of honor.”

Don’t be fooled by the complexity of each setting in the refectory. Hearst kept meals fairly informal; the plates are stoneware, the napkins are paper, and that’s bottled ketchup and mustard on the elaborate table. “Mr. Hearst always referred to this place as ‘the ranch,’ and this was his way of bringing it down home,” says tour guide Kathryn Keller. Photo: by Matt Guilhem / KCRW.

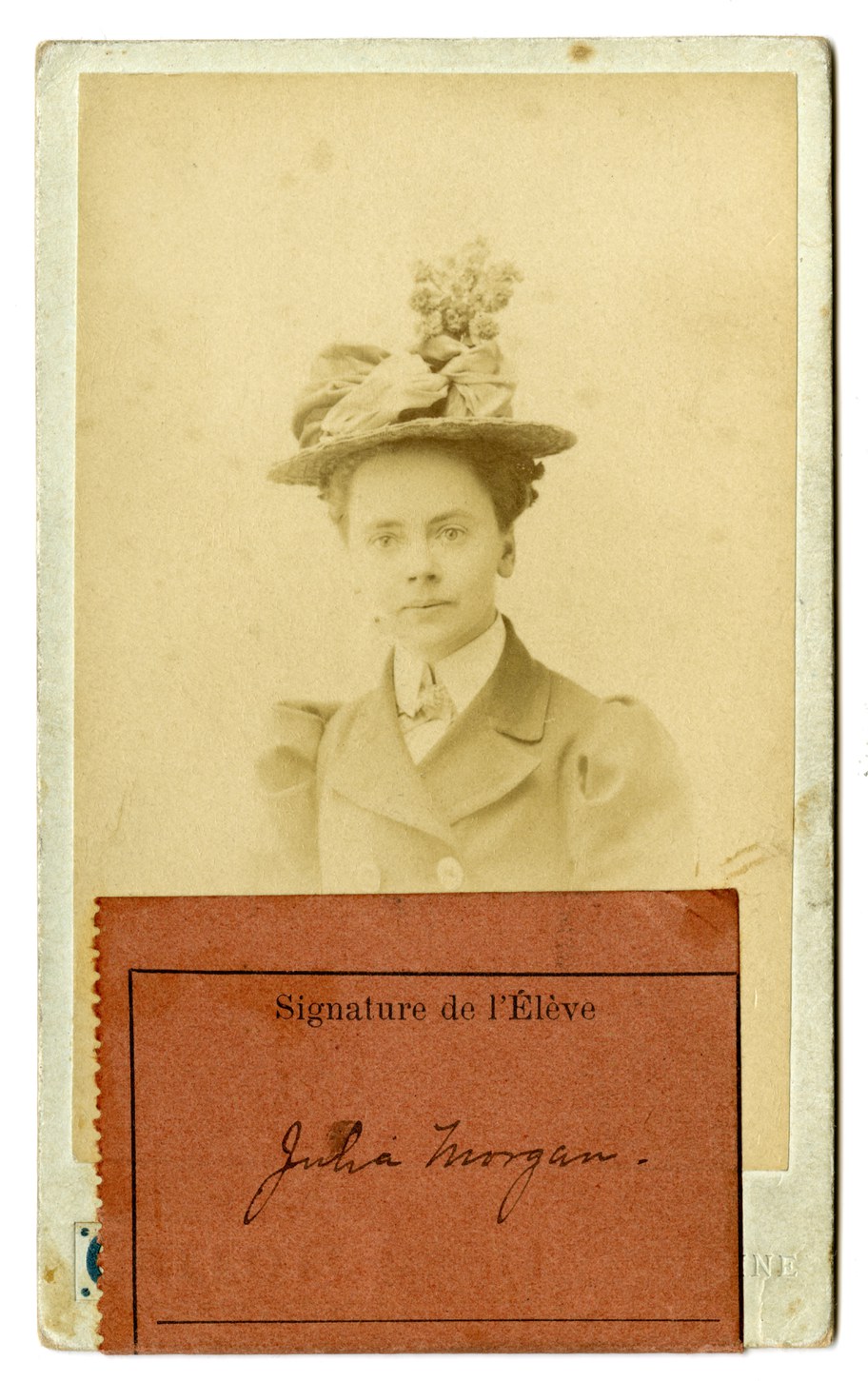

Upstairs, in the studio-style apartments that make up the north duplexes, displays on the wall spotlight Morgan’s young life and early career. Not only did she graduate from Berkeley in 1894 with an engineering degree, but she was the first woman to be admitted to the architecture program at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris at the close of the 19th century.

Born in San Francisco, Julia Morgan studied architecture in Paris at the world-renowned École des Beaux-Arts. Morgan’s student ID from 1899 is from the early period of her studies. Photo courtesy of Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo.

“When the news came back that she had won a place at the Beaux-Arts, of course it hit the front page of the Examiner,” Keller says. “And her father did say, ‘It seems as if I might go down in history as the father of the distinguished architect Julia Morgan.’”