Starting August 18, the public will once again be able to tour the first residence that renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed in LA: the 5,000-square-foot Hollyhock House. Located at Barnsdall Art Park in East Hollywood, the residence shut down during the COVID pandemic and underwent restorations to the cast stone work, art glass, wood finishes, and exterior finishes. The whole house was strengthened against earthquakes, and leaky roofs were fixed.

The house was commissioned by oil heiress Aline Barnsdall, who was planning to make it part of an arts complex. Wright completed it in 1921. Six years later, Barnsdall gave it to the City of LA, which has been running it ever since.

Hollyhock House is LA’s one and only UNESCO World Heritage Site, meaning its significance goes beyond national boundaries, influencing the development of architecture and culture at large. That’s according to curator Abbey Chamberlain Brach.

Aline Barnsdall’s favorite flower was the hollyhock, so Wright incorporated abstractions of it when creating bands of cast concrete stonework that run around the whole building, Brach explains. The stonework is influenced by Maya architecture.

Disdaining what he called "the tawdry Spanish medievalism" of Los Angeles' Spanish Colonial revival architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright looked instead to pre-Hispanic structures. He evoked rather than imitated Maya architecture with his design of Hollyhock House. Here on the iconic west facade, the pronounced slope of the upper walls resembles that of the Palace at Palenque in Southern Mexico. The cast-concrete ornamentation relates to the dense patterning of Maya façades that Wright admired. Photo by Amy Ta.

Aline Barnsdall's favorite flower was the hollyhock, and Frank Lloyd Wright incorporated it in the design for her home with geometric abstractions in cast concrete, art glass, textiles, and furnishings. Photo by Amy Ta.

The interior is known for lots of airflow and low ceilings. “Frank Lloyd Wright was 5’8,’’ so while he was a pretty average height for the period, it's about the design and how you feel moving through these spaces. So the low ceilings allow that sense of release as you move into the rooms themselves,” Brach says.

She continues, “Looking to the dining room just in from the foyer, there's a shift in ceiling height, and you really get a sense of arrival in the room itself.”

The dining room table and chairs from the 1921 house are still here today, she points out. The chairs have high backs that resemble the tall stalks of the hollyhock flower, and they’re reminiscent of vertebrae running through the human spine.

The dining room, just off the foyer to the left, has warm wood surfaces, hipped ceiling, and art glass windows. It possesses many features typical of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famed Prairie-style houses. However, here he created a less formal open space where moldings and a shift in ceiling height are all that distinguish the dining area from the kitchen pathway. Photo by Amy Ta.

Frank Lloyd Wright favored high-backed chairs in his dining room designs. Standing tall, they create an enclosed, intimate space for dining within the larger room. The original custom chairs here, gathered around a hexagonal table, feature an abstraction of the hollyhock that looks like vertebra and echoes the body of the person seated. Photo by Amy Ta.

Designed in the 1940s by Frank Lloyd Wright's son Lloyd Wright, this remodeled kitchen features solid mahogany countertops and a high-end custom stove. Embracing general elements of his father's original design for the house, Lloyd Wright favored clean, modern lines, which he can be seen here. Photo by Amy Ta.

Wright designed furniture for the dining room and living room — the most showy spaces here.

“Wright is well known for doing these total works of art … where he's integrating the design of furniture, textiles, the windows are variations on the Hollyhock motif, carrying all those design elements through, and also making recommendations on the type of objects that an individual would fill their home with,” Brach says.

She continues, “Barnsdall actually purchased the Japanese screens here at Hollyhock House — two sets that were used in the living room through Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Frank Lloyd Wright designed custom furnishings for Hollyhock House's living room and dining room. The oak furniture in the living room features abstractions of the hollyhock, frames views in the room, and provides surfaces for the display of objects. At the far end of the room, a pair of Japanese screens that Aline Barnsdall purchased from Frank Lloyd Wright extend the landscape views from the west windows into the room itself. Photo by Amy Ta.

The house’s most dramatic space is the living room, which features a fireplace that’s “one of the most show-stopping features.”

“We reinstated the moat bridge. And yes, there is a moat for this fireplace. It is a design that brings together the four classical elements … earth, air, fire and water. … Light [is] streaming in from up above with art glass panels. There is a cast stone designed relief … over the fireplace,” Brach describes.

At Hollyhock House, Frank Lloyd Wright experimented with a new design element, water. It originally ran through the house, linking the patio pool with another on the west façade. The water would have surfaced in the living room and was integral to the design of the show-stopping fireplace. Oversized sofas faced this focal point like a stage, where — with striking cast stone, art glass overhead, and a moat around the hearth — fire, earth, air, and water came together. The cast-concrete moat bridge has just been restored, completing this remarkable fireplace design. Photo by Amy Ta.

Wright believed the hearth was a home’s symbolic center, and his residential designs reflected its importance. Here the monumental fireplace boasts a spectacular bas-relief sculpture that features geometric abstractions of the hollyhock and other forms seen in the house. Constructed of 17 individual cast concrete blocks, the relief adds to Wright’s unified design with a dramatic effect that goes beyond merely hanging a painting over the fireplace. Photo by Amy Ta.

Brach says most of the furniture has been replicated in the 1990s. But recently, someone purchased the original small tables — that extend from the backs of large sofas — and returned them to the house.

“It's really a remarkable survival [story] that 100 years after this house is completed that objects are returning to the site.”

In 2021, Hollyhock House celebrated the return of two original Frank Lloyd Wright-designed sofa tables to the site. They are the only-known pieces of fixed furniture from the living room to survive. Photo by Amy Ta.

From the living room, visitors can walk out to the patio garden, where artificial turf has been added to the private lawn. A few hollyhock plants are growing, though the flower typically doesn’t do well in late summer.

A few hollyhock plants are still in bloom in Hollyhock House's patio garden, even in the summer. With blooms running up the plant's tall stock, the hollyhock inspired Frank Lloyd Wright's geometric abstractions across the site, including the cast-concrete capitals on the colonnade pictured here. Photo by Amy Ta.

The roofs of residence are also accessible from multiple stairways, where panoramic views show the Hollywood sign, Griffith Observatory, Century City, and downtown LA.

“Key to Wright’s design were these livable roof terraces that he designed here at Hollyhock House,” says Brach.

The roof of Hollyhock House was intended to be an outdoor living space for Aline Barnsdall and her daughter. This staircase leads to the living room roof with panoramic views of Los Angeles. Photo by Amy Ta.

Decorative cast-concrete finials flank stairwells on Hollyhock House's rooftop terraces, offering another variation on hollyhock-inspired abstractions and helping navigation across these outdoor living spaces. Behind each finial is a planter box (now capped to prevent interior leaks), which would have allowed for cascading vines to spill over Hollyhock House's rooflines, as seen in images of Maya ruins published in the early 20th century. Photo by Amy Ta.

This cast-concrete, roof-terrace finial designed by Frank Lloyd Wright features a mask-like detail evocative of pre-Hispanic stonework, which the architect admired. Photo by Amy Ta.

After guiding KCRW through the 5,000-square-foot space, Brach says, “I’m very excited to have people back at the house [so they can] experience the interiors once again.”

A 50-foot-long enclosed walkway leads to the front doors of Hollyhock House, creating a sense of anticipation on arrival. Photo by Amy Ta.

This south-facing sunporch has striking art glass and would have been a secure place for Aline Barnsdall's daughter, Betty, to play and an alternative to the adjacent terrace yard. Photo by Amy Ta.

The study holds nearly 1,000 books published in the 1920s or earlier. While only a few were owned by Aline Barnsdall, the collection represents her interests in art and literature, and most were gifts made by local community members. Photo by Amy Ta.

In 2021, curator Abbey Chamberlain Brach discovered a painting from Aline Barnsdall’s celebrated art collection for sale on eBay. With support from Project Restore, it has been returned to Hollyhock House. “Mountains” was painted by Edith Truesdell, a member of the California Art Club (headquartered at Hollyhock House from 1927-42) and an editor of the club’s bulletin during that vibrant period at the house. Photo by Amy Ta.

In 1921 as Frank Lloyd Wright was finishing Aline Barnsall’s home, she purchased “Three Dancing Nymphs,” a first century Roman relief. She described it as "the thing I love most, except for my relatives," and installed it in the loggia. In 2016, this plaster replica was created from the original (now on view at the Getty Museum) using 3D scanning and computer numerical controlled (CNC) milling. Photo by Amy Ta.

Running along the north side of the center patio, this long colonnade leads to Hollyhock House's foyer from the servants' area. Photo by Amy Ta.

Gifted to Hollyhock House in 2019 by then curator Jeffrey Herr, this Behr Bros & Co. baby grand piano is at home in the music room. Frank Lloyd Wright long saw a link between music and architecture and used the musical term for free form in describing Hollyhock House as a "California Romanza,” capturing the commission's creative potential. Photo by Amy Ta.

This 1923 aerial view shows Hollyhock House at the center of Aline Barnsdall’s 36-acre property, Olive Hill. The house was intended to be the centerpiece of a large arts complex, which was only partially realized. Note two figures waving from the home’s roof terrace above the living room. Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library, Security Pacific National Bank Collection.

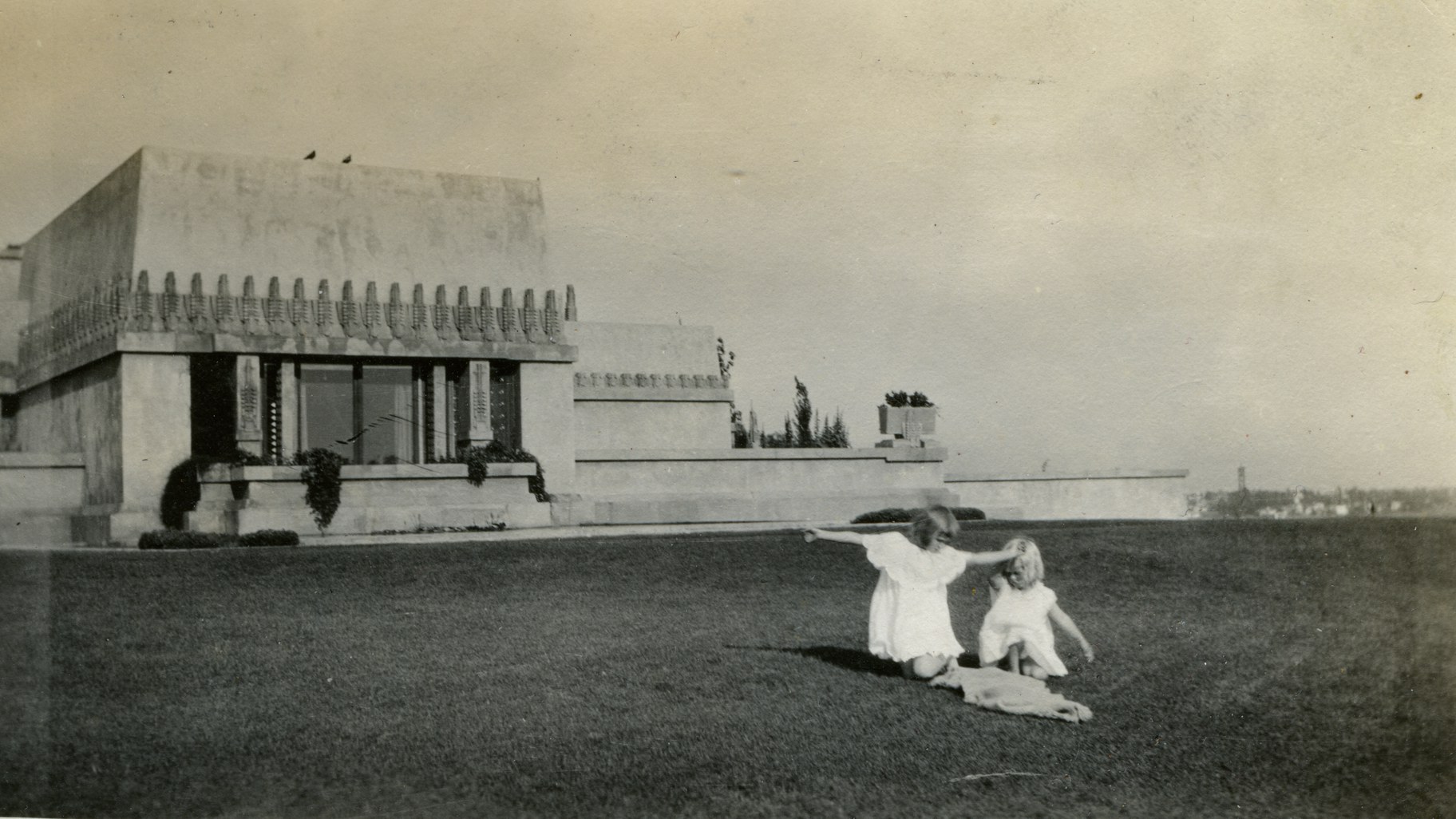

Aline Barnsdall’s daughter, Betty, and a friend play on the west lawn at Hollyhock House, circa 1923. Credit: Collection of David Devine and Michael Devine, courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and Hollyhock House.

Hollyhock House’s living room is seen circa 1921. Photo curtesy of the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and Hollyhock House.

This portrait of Aline Barnsdall was shot in 1916 for the Little Theatre of Los Angeles. Credit: Collection of David Devine and Michael Devine, courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and Hollyhock House.