Carmakers from BMW to Ford to Nissan are pledging to invest billions of dollars in the coming years to electric car manufacturing, while the state of California will ban the sale of new internal combustion gas cars by 2035. Yet with electric vehicles (EVs) making up only 1% of cars on the road in 2020, most car mechanics working today have had no training or experience with EVs. That’s about to change.

Ten years down the road, “I think [you will] have to learn it if you want to be a tech,” says Douglas Cook, an automotive instructor at Pasadena City College.

Local students are looking ahead. An introductory electric car repair course not required for the auto technician program at Pasadena City College has a waitlist, says Wendy Lucko, who updated the school’s auto tech training program five years ago.

Joshua Warton, a student in the class, spent a recent morning learning how to safely disable a high voltage electric battery. Afterwards he was pragmatic about the new skills. The change to electric vehicles “is inevitable,” he said. “Might as well embrace it.”

These students “understand that they need to be comfortable with this because they probably will stay in LA, and they see the future,” says Lucko.

Pasadena City College student Gabriela Martinez puts on insulated gloves that protect against high voltage electric shock, while classmate Jose Marroquin prepares a voltmeter to see if the electric battery they disabled still has electric current. Photo by Megan Jamerson.

In fact, demand for these skills is already starting to climb.

John Frala, who teaches courses on alternative fuel technologies at Rio Hondo College in Whittier, says companies are calling him daily, saying they have job openings for techs they need immediately filled. “I can't train [students] fast enough to get them out of here.”

But that doesn’t mean they are all excited about electric vehicles.

While some students are inspired by Tesla’s engineering, Cook says most of his students grew up idolizing sleek gas-powered sports cars.

“You're not putting a [Chevrolet] Bolt on your wall, a poster on your wall with that,” he says.

But the future won’t be all utilitarian electric commuter cars, thanks to romantics like automotive designer Stewart Reed. He chairs the transportation department at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, a global leader in automotive design, where Reed thinks a lot about the deep connection we have to our cars.

“There's still this underlying love affair … for a whole lot of reasons,” says Reed. “You look at the Southern California map, and it grew in no small part because of the automobile.” The car is now a large part of the identity of Angelenos, symbolizing the Western ideals of freedom and individualism.

“But it's also had all kinds of negative impacts,” says Reed. “So I think that's the honest debate that we really need to have. We don't want to blindly go on loving something that's hurting us.”

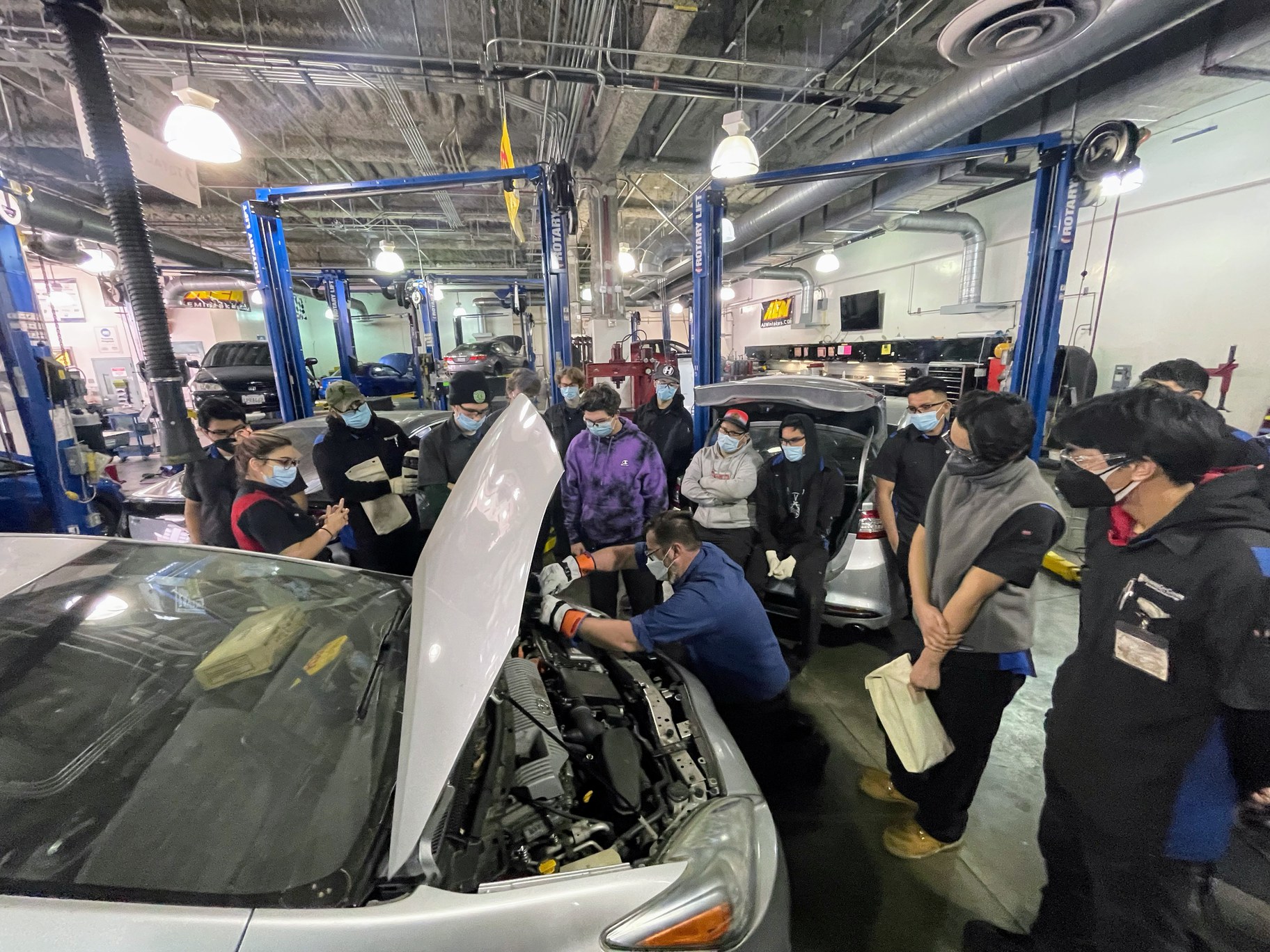

A class of automotive technician students at Pasadena City College watch their instructor, Douglas Cook (center), demonstrate how to safely disable a high voltage battery on a hybrid electric Toyota Prius. Photo by Megan Jamerson.

But gas cars aren’t going to magically disappear when the state stops selling new ones in 2035, and there also will be people who don’t want to give them up, says Douglas Cook. “We joke that we'll end up with a Cuba situation where there's going to be people that just do whatever they can to keep them going and never let them die.”

And for the auto tech students who don’t want to work on electric cars, Wendy Lucko doesn’t pressure them. Not everyone is meant to work with high voltage technology, she says. “We understand that. … We still need guys and girls to change our oil.”