In 1963, a group of Black photographers and their friends in New York City were tired of the media and art world not showing Black life. And so, they formed the Kamoinge Workshop — dedicated to capturing quotidian and extraordinary things in their personal lives and the world around them.

Now the images are part of a new exhibition at the Getty Center called “Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop.” It runs until October 9.

Named after a phrase that means “working together” from the Kikuyu language of West Africa, the Kamoinge Workshop held regular meetings throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, in which members discussed art, music, and photography, dissecting each other’s works and sharing techniques.

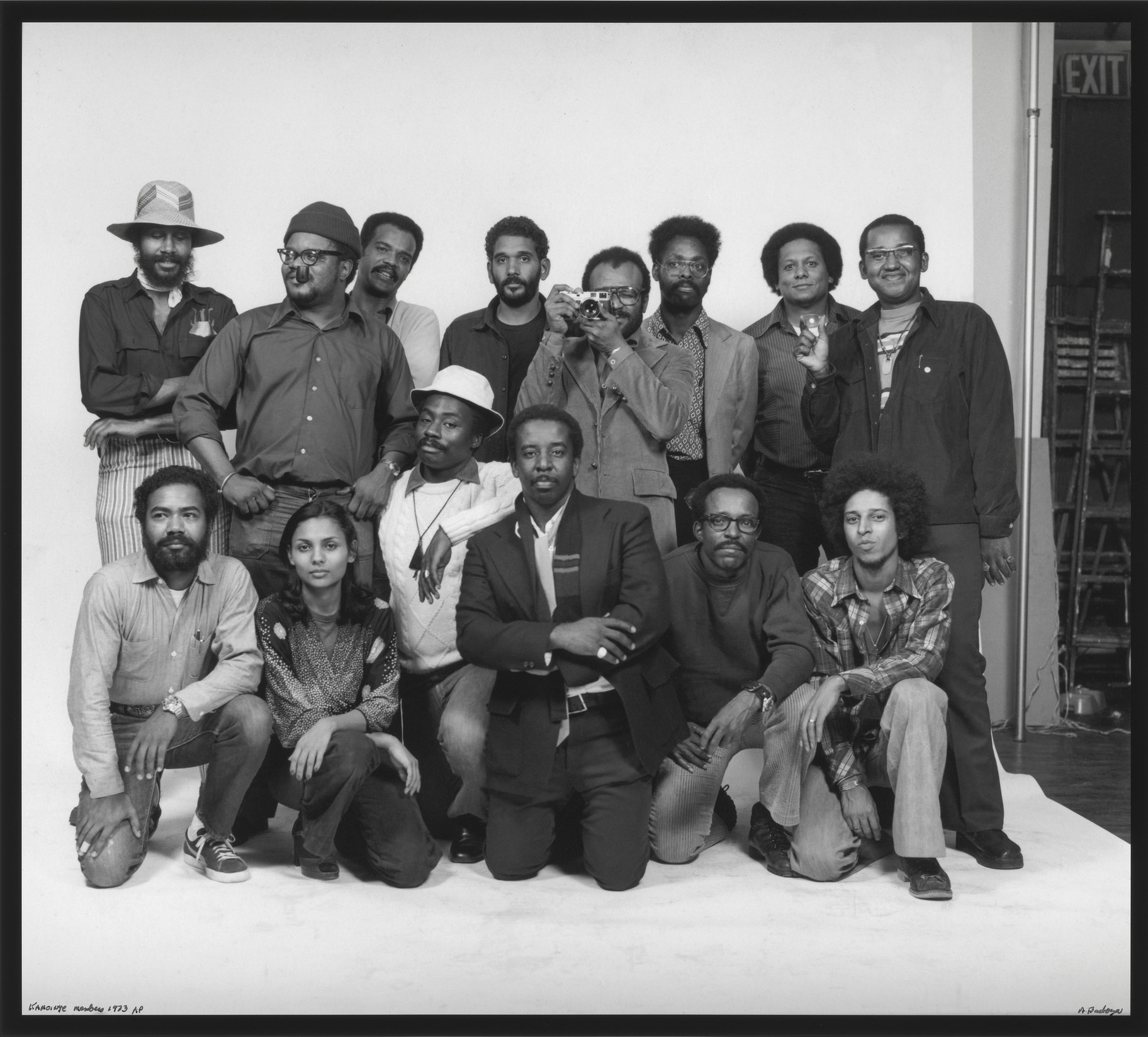

The Kamoinge group poses for a portrait, 1973. Photo by Anthony Barboza. Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.

When photographer Anthony Barboza joined, he was the workshop’s youngest member, and thought of the artists around him as his “older brothers.”

“I was overwhelmed by everything I learned, just like that, by sitting at the meetings,” says Barboza. “One of the members would put up a photograph, and they would dissect it and say whether they liked it or not. … It was wonderful to be in this group.”

Barboza later served as the president of Kamoinge from 2005 to 2016. He describes wandering the streets of Harlem, looking for ways to show the “positiveness and beauty” of the Black community.

Boys gather on Easter in Harlem, New York, in this photograph by Anthony Barboza. Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.

Photographing everyone from young men on the streets in their Easter finest to iconic figures like Malcolm X and Grace Jones, he often talked with his subjects instead of rushing in to take a photo. Getting to know them was one way to help them loosen up.

“I was feeling them and they're feeling me, so I wanted to get something from them. … I always say that the photograph finds you, you don't find a photograph, so your patience is always important in that sense,” says Barboza.

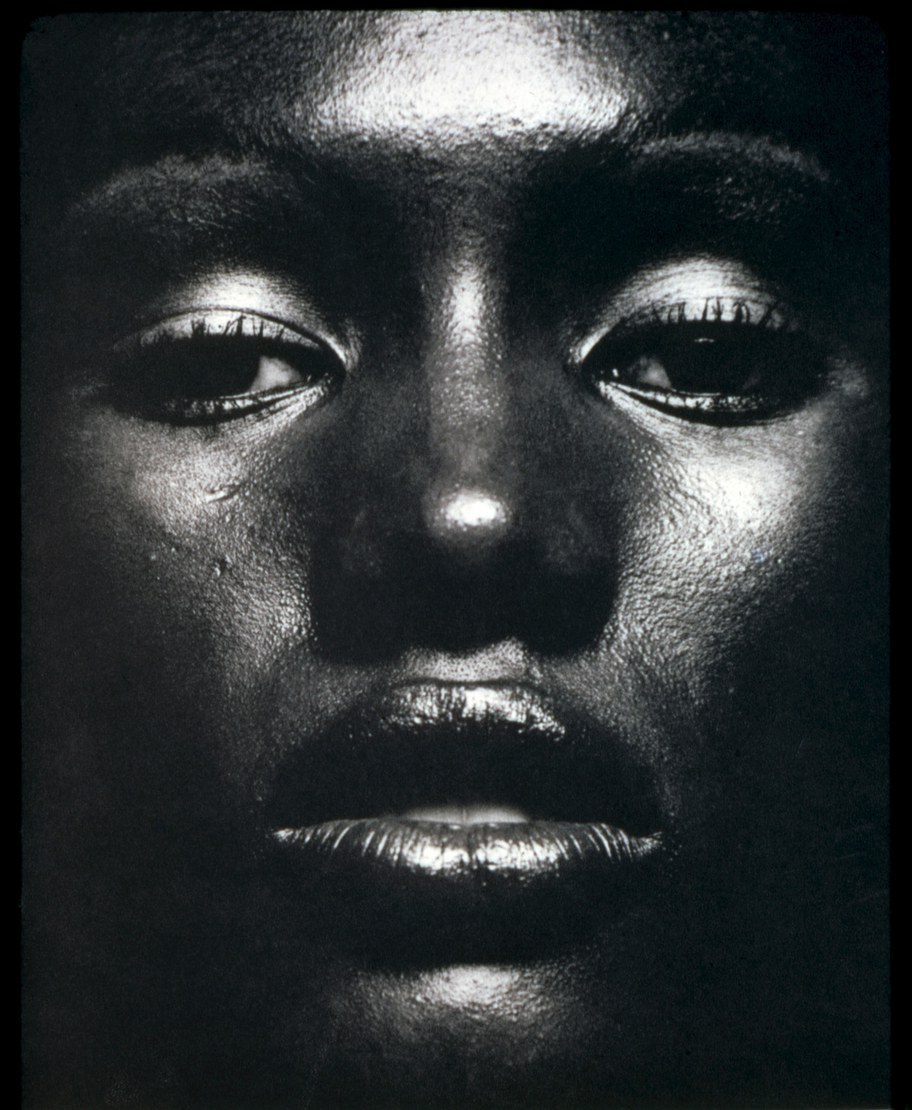

Anthony Barboza captured this portrait of Grace Jones in 1970. Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.

Dolores McDavid, who stumbled across the exhibition by chance while visiting the Getty earlier this week, says she was incredibly moved by the images before her.

“I did not know about the exhibit until I arrived at the Getty Center, did not hear about it, did not know about it. [Then I] came across this one — [it] blew my mind,” she says. “What I see here represents me.”

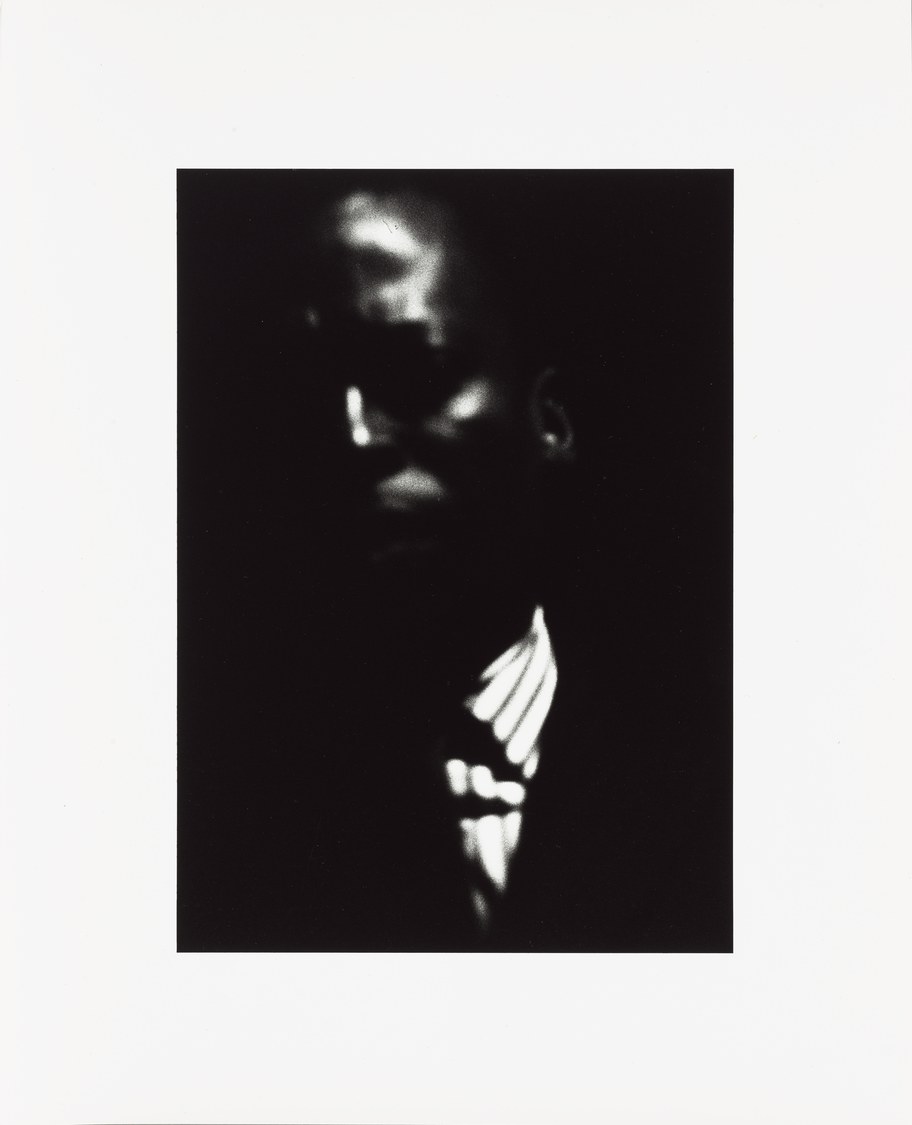

Herb Robinson photographed Miles Davis at the Village Vanguard. Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.

Barboza says the photographs demonstrate the beauty of the Black community and the realities of their daily lives. He adds that the images can serve as a powerful political statement, and are more impactful than any speech a politician could give.

“Showing a photograph is sometimes better than talking, you can just look at it and feel something for yourself. It gives you something back, if you view it,” says Barboza. “There's lots of times a politician gets up there, and you don't receive anything, even though he's talking like he's giving you something.”

Albert Fennar’s 1971 photograph is titled “Salt Pile.” Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.

Getty Center curator Mazie Harris says part of the show’s power comes from its ability to highlight issues that would otherwise go overlooked, while representing a full and relatable spectrum of experiences.

“That's what we hope for when we go to museums, right? To find connection,” Harris says. “And I think this work really does that. There's such a variety of work. There's community work, there's civil rights work, there's work about jazz. There's work about global travels. There's really incredible abstractions. I really think there's something for everyone in this exhibition.”

A few of the members of the original Kamoinge Group gathered at The Getty for the show’s opening in July. L-R: Herb Robinson, Adger Cowans, Anthony Barboza, Herb Randall, Jimmy Mannas. Photo by Alexio Barboza. Photo courtesy of the Getty Center.