Greater LA

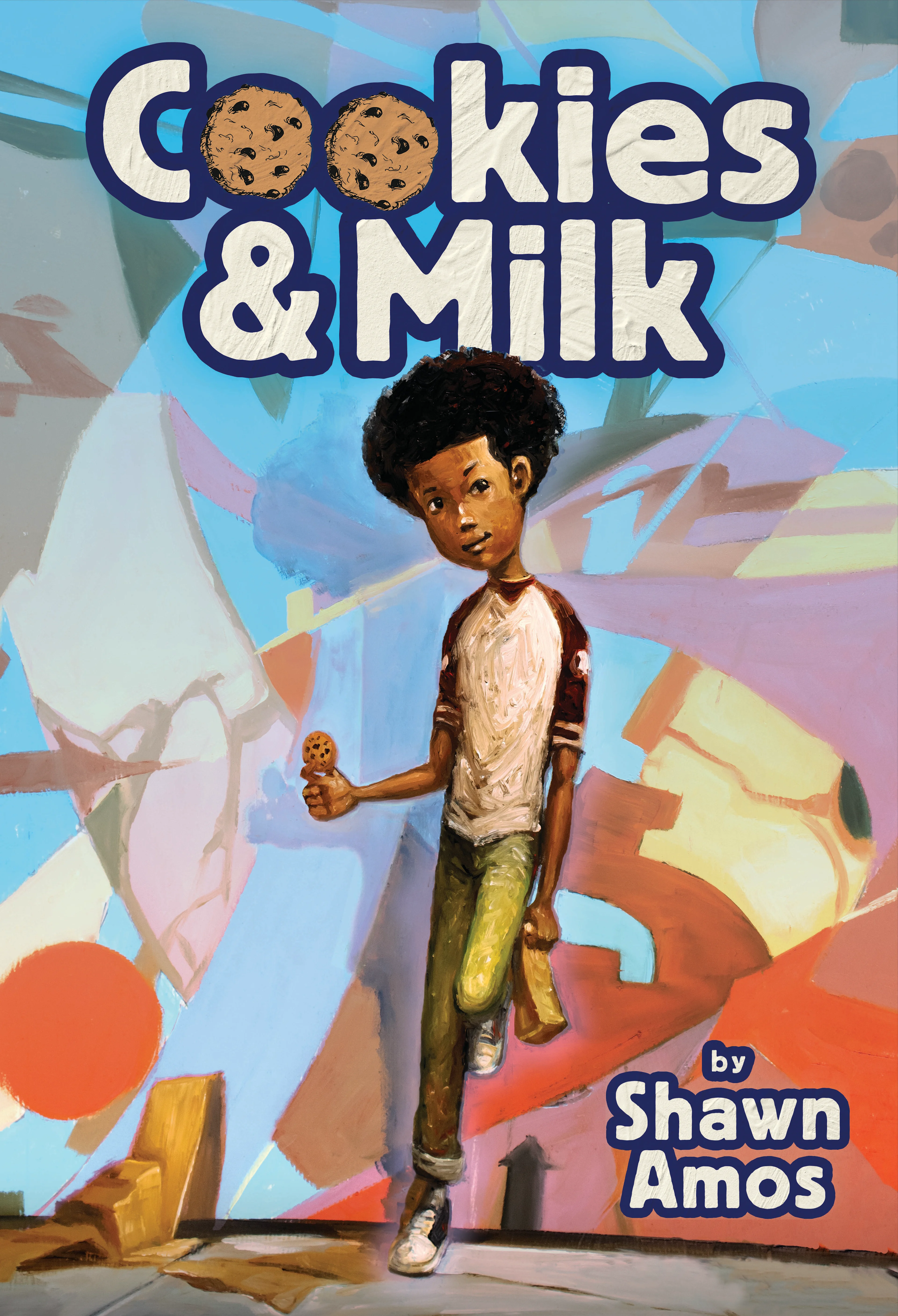

Son of ‘Famous Amos’ reframes pain into joy in debut novel

In his debut novel, “Cookies and Milk,” author Shawn Amos – son of the entrepreneur behind Famous Amos cookies – finds joy from a troubled childhood.

In 1975, a talent agent named Wallace “Wally” Amos, Jr. bought a run-down A-frame storefront, loaded up on flour and chocolate chips, and opened what would become one of America’s most beloved cookie stores: Famous Amos.

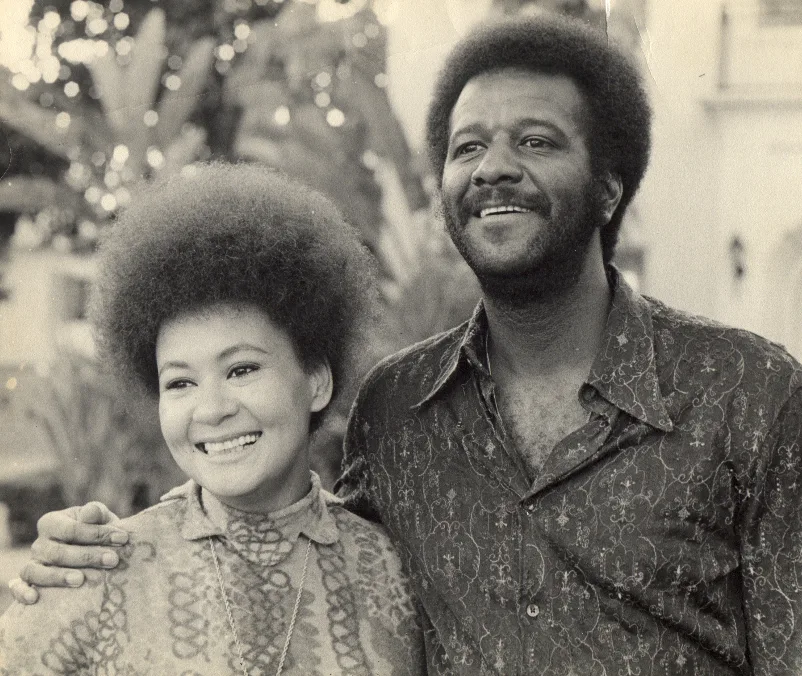

But as Amos’ star rose, his ex-wife’s flickered. Shirley Ellis, a beauty queen and nightclub singer known as Shirlee May, was privately struggling with severe mental illness.

Shirley and Wally’s witness was their son, Shawn Amos, who grew up behind the counter, serving cookies to the eclectic clientele of Hollywood’s Sunset Strip.

In “Cookies and Milk,” his debut novel for young readers, Shawn Amos writes about his childhood and grapples with his own experience of fatherhood.

The loosely autobiographical story follows a young boy named Ellis — named after Amos’ own son — as he helps his dad open a cookie store.

For Amos, the novel was an exercise in reframing a challenging childhood.

Amos’ father, the entrepreneur William “Wally” Amos, opened the store after a career as the first Black talent agent for William Morris Agency, now called William Morris Endeavor. Amos says his father booked acts like Simon and Garfunkle and The Animals, but he wasn’t very present in his son’s life.

“He was a hustler,” Amos says. “I think fatherhood was truly an afterthought.”

Wally Amos ultimately lost his business and his fortune, his son says. He is now living in Hawaii and suffering from dementia.

Meanwhile, Amos’ mother, Shirley Ellis, struggled with schizoaffective disorder, and died by suicide in 2003.

“I spent so much of my life just trying to come to grips and live peacefully with all of the darker stuff that filled my early life,” says Amos, who is now a father of three, and recently divorced.

In “Cookies and Milk,” Amos wanted to reframe his story.

“I began to sort of retrace my memories of the cookie store, which I realized were really joyful,” says Amos. “That spot was a real safe haven for me, and it really inoculated me from a lot of the pain that existed elsewhere.”

Amos says the writing process helped him gain empathy for his father.

“What he did was remarkable,” Amos says. “He was the Black face of a business at a time when there were virtually none.”

Amos’ writing also helped him reconnect with his teenage son. In the dedication of the book, Amos writes, “This book is for my son and my father. I stand between you both, as the three of us nurse our wounds across generations. This story is the bridge I built for us.”