One morning in 2020, Carrie Lederer walked out of her rent-controlled bungalow in Santa Monica, hopped into the 2008 Toyota Prius parked in the spot she’s used for 20 years, punched on the ignition, and heard a loud rumble blasting from under the car. It could only mean one thing: Her catalytic converter had been stolen.

“They got me,” Lederer recalls thinking. And so began a saga that would cost her thousands of dollars and many hours spent on paperwork and repairs, leave her dependent on her bike for transportation, and keep her dealing with car repairs for more than three years.

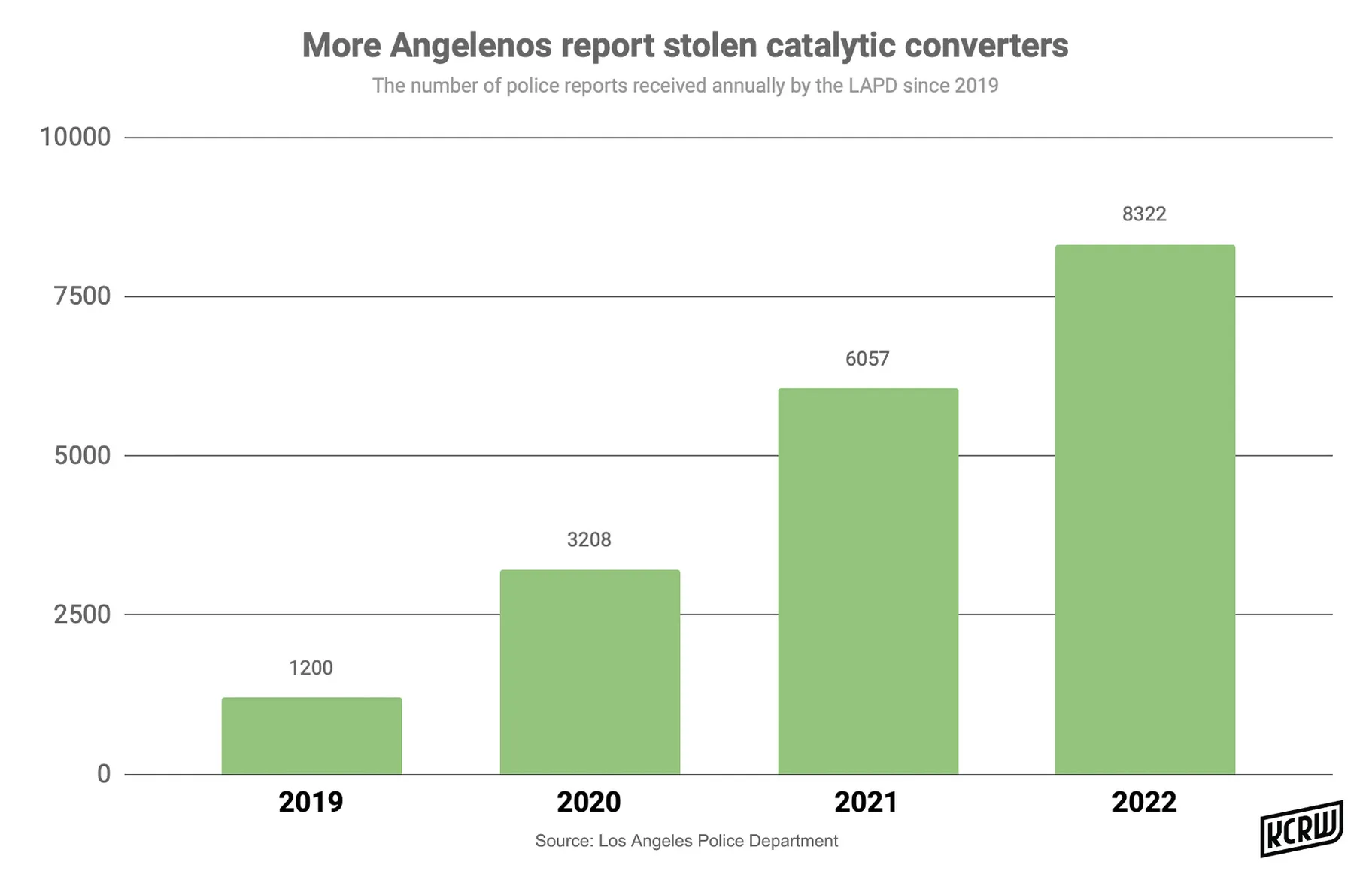

Catalytic converters are emissions-reducing devices that are part of a car’s exhaust system, and they’re loaded with precious metals like rhodium and platinum. In the past several years, a booming market for those metals has emerged, and thieves have noticed. The National Insurance Crime Bureau reports theft claims more than tripled between 2021 and 2022. California leads the nation for these claims, and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department calls the region a “hotspot” for the crime, with an estimated 19,000 catalytic converters stolen in 2022.

More: Explainer: Catalytic converter thefts, and what to do about them

This figure shows an increase in the number of reported catalytic converter thefts received by the aLAPD since 2019. Figure by Gabby Quarante/KCRW.

One week in April, customers brought in nine cars missing their catalytic converters to Luna’s Performance and Exhaust in Van Nuys and “it’s getting crazy,” says owner Dan Luna.

The sharp spike in thefts means drivers are waiting months for backordered parts, insurance companies are paying tens of millions of dollars in claims, and auto repair shops are swamped. Carrie Lederer didn’t know it yet, but she was on the leading edge of an unfortunate trend. And she was about to find out just how overwhelmed the system has become.

Edward Luna holds two out-of-commission catalytic converters. Metal recyclers pay anywhere up to $250 to extract and sell the trace metals they contain, creating a booming market for stolen parts. Photo by Megan Jamerson/KCRW.

The police

After discovering the missing part, Lederer filed a police report. She says the Santa Monica Police Department thanked her for the information but told her not much could be done since the thieves were not caught in the act. “So that was really disheartening,” says Lederer.

Still, police want victims to file reports, the Santa Monica Police Department tells KCRW. “We really can do things that may be able to save somebody else's catalytic converter in the future,” says SMPD spokesperson Lieutenant Erika Aklufi. Reports help them decide where to dispatch patrols, and in some cases that has led to catching thieves in the act, says Aklufi.

But it’s rare for an arrest to be made for any individual theft. That’s because under current law, when loose parts without receipts are found, it’s difficult to prove a crime has been committed, says Sheriff’s Captain Martin Rodriguez, the lead officer of LA County’s Taskforce for Regional Auto Theft. Parts typically lack a way to link them back to the original owner, which also means if a stolen part is recovered, it’s rarely returned to the victim.

The LA City Council is attempting to address rising thefts with an ordinance that will increase the criminal penalties for possessing a catalytic converter without proof of ownership. That law goes into effect on June 5.

Critics of the ordinance, including Coucilmember Eunisses Hernandez, say the law could disproportionately affect low-income Black and Brown communities. She worries it will provide more opportunities to criminalize these communities which have historically been over-policed.

But law enforcement officials like Rodriguez say they need this tool. “If enough people have some fear of consequences, then that is often a deterrence,” he says.

The insurance company

After filing a police report, Carrie Lederer called her insurance carrier and found out her limited plan would not cover the part, which meant she had to pay out-of-pocket for a replacement.

The new part totaled $3,000, and Lederer paid another $500 for a mechanic to install a metal shield around the catalytic converter. “They thought that maybe it would take them longer to cut the catalytic converter,” says Lederer. In a lot of cases, thieves are not stopped by protective devices like shields and cages.

This work took about three weeks, a long stretch for her to be without a car. When she got it back, she had the Santa Monica Police etch her license plate number on the catalytic converter for free. This could make it easier for law enforcement to identify the part as stolen if it was taken again.

In January, two years after that fateful rumbling morning, the shield around Lederer’s catalytic converter failed its crucial test. Thieves made off with the part for a second time. “Of course, it was stolen again,” Lederer recalls thinking.

This time Lederer had comprehensive insurance, so after she paid a $500 deductible, the replacement part was covered. When an insurance adjuster came out to inspect the car, Lederer recalls asking in amazement, “‘Are you just going to continue to keep paying this over and over? I mean, what if it's every two weeks?’”

Lederer got her answer the hard way. Two weeks after the part was replaced in February, the catalytic converter was stolen for a third time. “Obviously, I can't leave my Prius with the catalytic converter in, on the street, because I'm a target,” says Lederer.

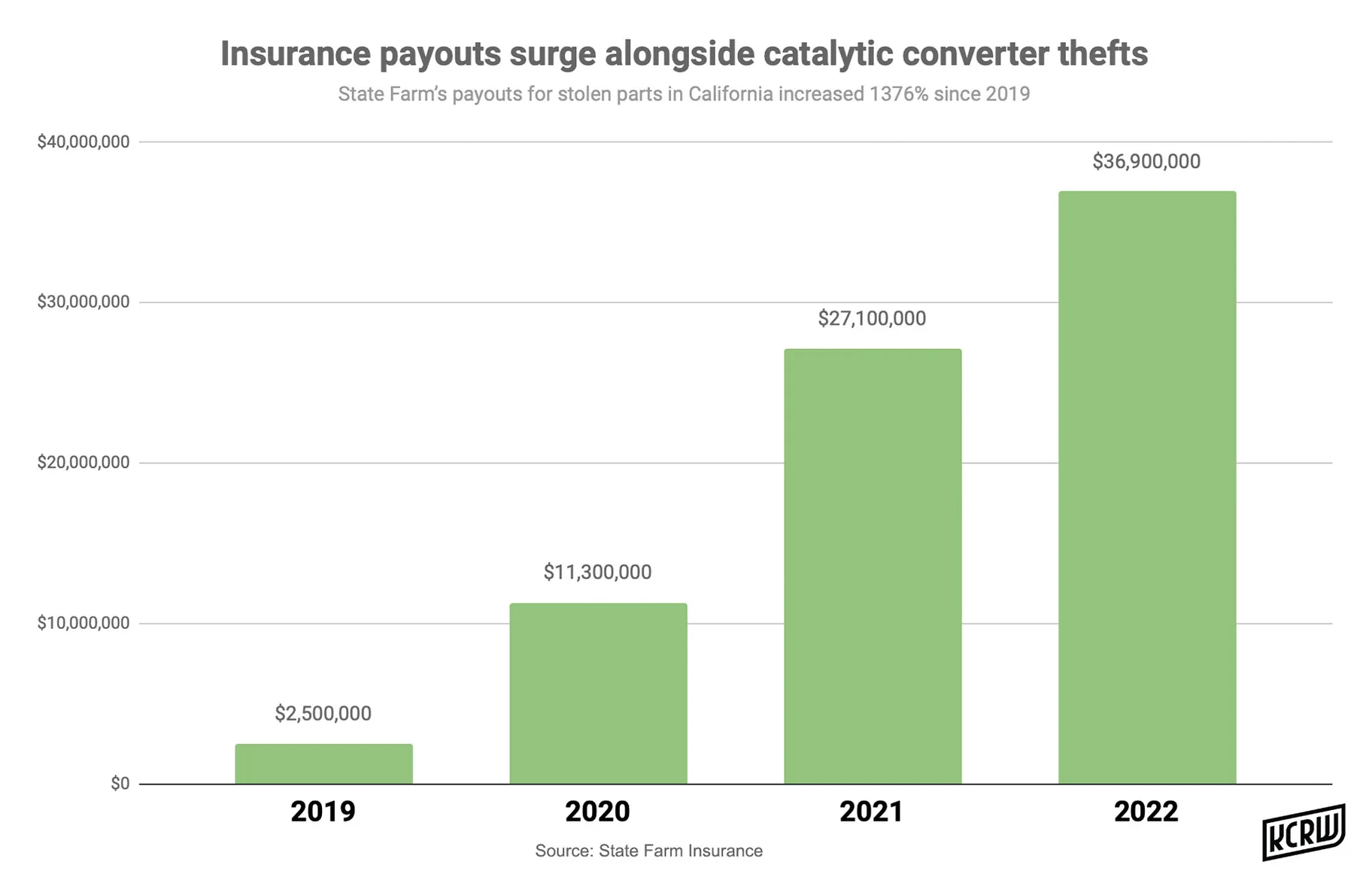

The crimes are costing insurance companies a lot of money. State Farm tells KCRW that the company paid $36 million in catalytic converter theft claims in 2022, just in the state of California. That’s more than a 1300% increase in payouts since 2019.

The figure above shows a rise in how much State Farm is paying in theft claims for catalytic converters since 2019. Figure by Gabriela Quarante/KCRW.

This time she was angry, Lederer says. She’d purchased a hybrid vehicle because it was better for the environment. Now, as the owner of a Prius, her car was a target because its catalytic converter contains more of those valuable trace metals than other hybrid makes and models.

Lederer says it feels like she and other victims have no recourse to protect their cars, especially if parking on the street is their only option. In her case, a protective shield didn’t stop thieves and the identifying information she had etched on the catalytic converter hasn’t yet led to an arrest.

“As long as the thieves are getting away with it, and making a good living, I don't see them stopping anytime soon,” says Lederer. “It feels impossible.”

Parts suppliers

As Lederer’s insurance wrote a check to her local Toyota dealership for a third catalytic converter, she faced a new problem: The part was backordered because of demand due to thefts and the global supply chain crisis. So three months after the most recent theft, Lederer had no catalytic converter on her car, rendering it undriveable.

Long wait times mean some people are offering victims workarounds to drive their car before it’s repaired.

Which explains something curious that happened to Lederer that morning three years ago after she turned her car on and heard the horrible no-catalytic-converter noise. She was approached by an employee from a nearby smog testing shop who handed her a card advertising used catalytic converters. “Which I thought was rather fishy,” says Lederer.

Cars with used catalytic converters are not street legal, says the California Air Resource Board (CARB), the state regulator that certifies vehicles and replacement parts meet emissions standards.

Other illegal temporary fixes include installing a straight pipe to muffle the noise when the catalytic converter is missing, and patching up the exhaust system to allow a car to pass their smog test without one.

The reason the state has such strict rules around the emissions systems of cars in the first place is because of the impact the catalytic converter has had on air quality since it became required in 1975. California still has some of the worst air quality in the country, but it’s cleaner than it was 50 years ago. And that’s been possible in large part because of people maintaining the integrity of their vehicle’s catalytic converter and broad support for the state’s smog check program, says John Swanton, a spokesperson for CARB. “It's something that everybody's … contribution has made a huge difference,” he says.

Meanwhile, as Lederer waited for a part, she got around town mostly on

her mountain bike. She says she feels lucky to live in walkable Santa Monica, with a job that doesn't require a daily commute.

Carrie Lederer relied on this bike to get around Santa Monica while she waited for her car to be repaired. She described the past five months as a test to see if she really needed a car. Photo by Megan Jamerson/KCRW.

After three months of waiting, Lederer finally got the call from Toyota. They had a part and she could bring her car home. With no end in sight to catalytic converter thefts though, she says she might sell her car and stick to cycling.

“Maybe I just don't even need a vehicle,” says Lederer. “Because I sure as heck don't want to spend $500 every two weeks.”

KCRW’s Danielle Chiriguayo and Andrea Domanick contributed to this report.