Nestled between warehouses and office buildings along the outskirts of Camarillo, an hour north of Los Angeles, exists a little-known museum with a massive collection of natural wonders: more than 1 million preserved bird eggs, the largest collection of its kind in the country.

This is the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. Inside the museum and research institute, stuffed ducks and geese line the walls. Seagulls hang under fluorescent lights as if they are in flight. Condors in glass vitrines perch atop rows and rows of cabinets, alongside woodpeckers, pelicans, and tiny backyard birds. Inside the cabinets are more than 250,000 sets of eggs.

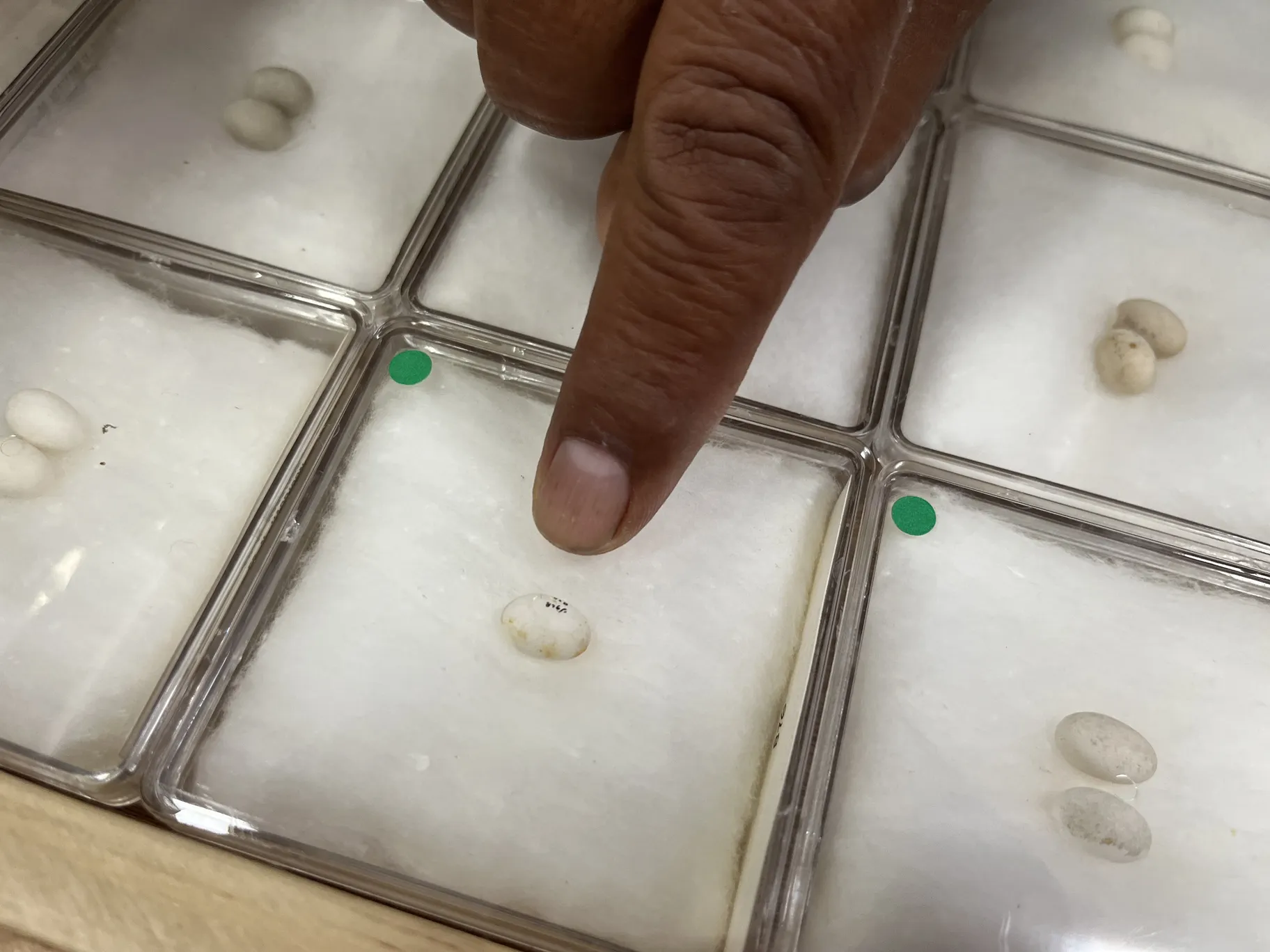

Biologist René Corado is their caretaker. He also prepared most of them for preservation. The worst are hummingbird eggs, he says. “You don’t drink coffee before you do a hummingbird because you might break the egg.”

Biologist and collection manager René Corado cleans, preserves, marks, and labels every egg of the collection, including tiny hummingbird eggs. Photo by Kerstin Zilm.

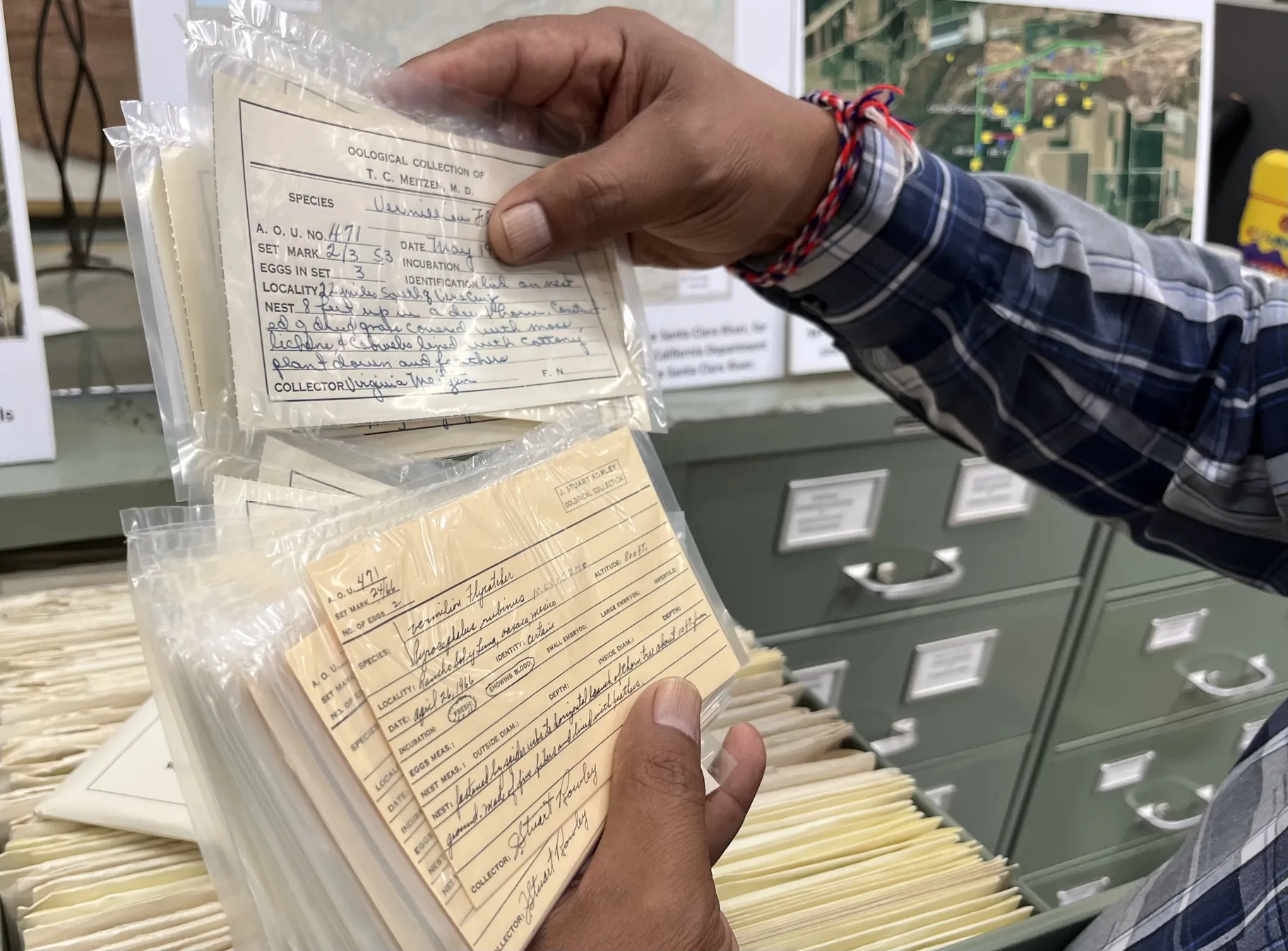

A significant portion of the museum’s treasures were gathered by rich bird hobbyists from Europe and the United States during the 1800s and early 1900s, when egg collecting was considered a fun pastime. They traveled around the world and came back with cases full of eggs. Many of those are now in Camarillo, Corado explains.

“We have about 500 collections. We are a collection of collections,” Corado says. “At that time, you didn't need any permits. Now nobody can collect eggs unless they are doing research.”

One of those egg collectors was Los Angeles wildlife photographer Ed Harrison. By 1956, he owned 11,000 sets of eggs. To store them, he built a private museum for them behind his home in Brentwood. Corado met Harrison there in 1982 while working as a gardener on his property. He had just arrived in LA from Guatemala the year before.

Corado says that as a little boy, he liked to climb trees to look at birds’ nests. But in third grade, he started working as a shoeshine boy in Guatemala City. At the age of 21, he started his journey north to escape violence and poverty in his home country.

René Corado poses in front of the Guatemalan flag and a mural of the country’s national bird, the quetzal. Photo by René Corado.

When Corado arrived in Los Angeles, he worked as a welder, dish washer, cook, and gardener. His gardening job led him to Harrison. The egg collector encouraged him to learn English, get a high school diploma and associate’s degree, and become a biologist. Corado also got a lot of hands-on experience working with Harrison in the field.

“He was the one who taught me all of this. I call him my gringo father. I love that guy,” Corado says.

Harrison continued to grow his collection even further, turned it into a nonprofit, and in 1992 moved it to the bigger space in Camarillo, where it remains today.

Each set of eggs is labeled with information about the time, place, and condition when it was collected. One of Corado’s tasks is to digitize what’s on the index cards. Photo by Kerstin Zilm.

The collection is still growing, despite the fact that the permits to gather eggs, birds, and nests are now hard to get. U.S. Customs and Border Protection sends confiscated goods from smugglers to the museum. The museum also takes in birds that were killed in car accidents or by cats, and it collects abandoned nests and eggs found in backyards.

Scientists from around the world come to study these eggs in Camarillo. They measure, for example, thow thick or thin their shells are, according to executive director Linnea Hall.

“If a female bird were to incubate the egg, would it actually withstand her weight when she sits on it, or is it going to collapse and kill the chicks?” Hall says. “Which could mean that those particular females are not laying thick shelled eggs anymore.”

This kind of study helped prove the insecticide DDT was decimating the population of some bird species, like the bald eagle. The chemicals caused the birds to lay thinner eggs that often never hatched, bringing the national bird close to extinction. The research convinced the EPA to ban the use of DTT in the U.S. in 1972.

Scientists study the effects of climate change, pesticides and pollution on birds, eggs, and nests. This nest, made from fishing lines, will not shelter small birds from heat and cold. Photo by Kerstin Zilm.

More than 5,000 research projects have been done with the eggs in Camarillo, and an internship program supports the next generation of egg scientists. René Corado has also established a relationship between Camarillo and La Universidad del Valle in the capital of his home country.

Jimena del Cid, a Guatemalan biology student and intern at the museum, says she is very interested in the role of birds in the environment.

“They are an indicator in the space they occupy,” she says. “They are very important for conservation and restoration.”

Corado loves to pass on his knowledge. He was named Ambassador of Peace by the government of Guatemala and received the country's highest honorary award: the Order of the Quetzal, named after Guatemala’s national bird.

He also wrote a bilingual book about his story. It includes lessons he learned from caring for more than 1 million eggs.

“How delicate life is, and how fragile the planet is. Birds are the fire alarm that we have at home. Their eggs tell me how fragile life is, how on the edge we are,” Corado says.

So far, he has not broken a single egg in the collection. Not even that of a hummingbird.