The anesthetic ketamine can relieve depression in hours and keep it at bay for a week or more.

Now scientists have found hints about how ketamine works in the brain.

In mice, the drug appears to quickly improve the functioning of certain brain circuits involved in mood, an international team reported Thursday in the journal Science. Then, hours later, it begins to restore faulty connections between cells in these circuits.

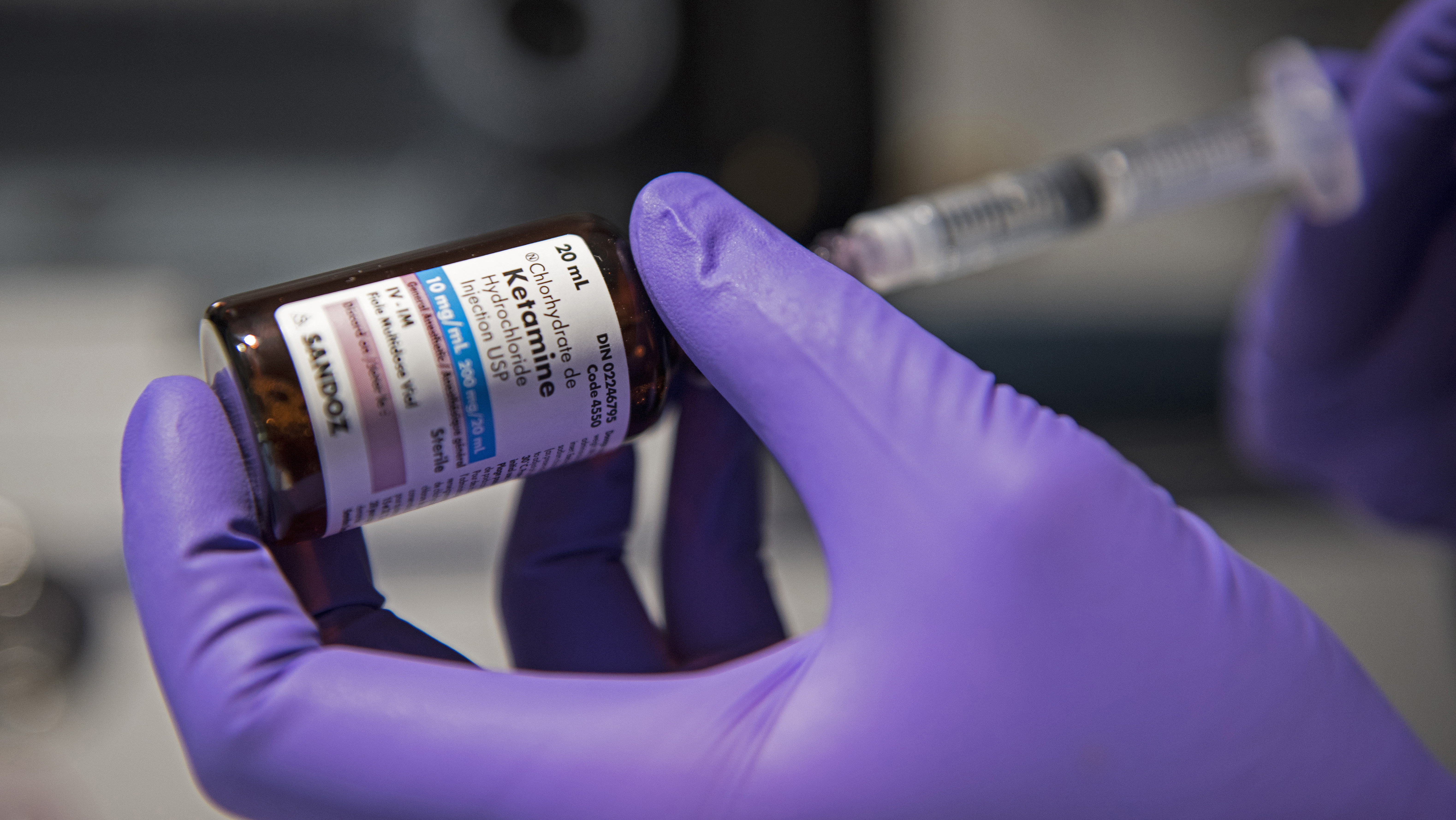

The finding comes after the Food and Drug Administration in March approved Spravato, a nasal spray that is the first antidepressant based on ketamine.

The anesthetic version of ketamine has already been used to treat thousands of people with depression. But scientists have known relatively little about how ketamine and similar drugs affect brain circuits.

The study offers "a substantial breakthrough" in scientists' understanding, says Anna Beyeler, a neuroscientist at INSERM, the French equivalent of the National Institutes of Health, who wasn't involved in the research. But there are still many remaining questions, she says.

Previous research has found evidence that ketamine was creating new synapses, the connections between brain cells. But the new study appears to add important details about how and when these new synapses affect brain circuits, says Ronald Duman, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Yale University.

Studying ketamine's antidepressant effects in mice presented a challenge. "There's probably no such thing as a depressed mouse," says Dr. Conor Liston, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York and an author of the Science paper.

So Liston and a team of scientists from the U.S. and Japan gave mice a stress hormone that caused them to act depressed. For example, the animals lost interest in favorite activities like eating sugar and exploring a maze.

Then the team used a special laser microscope to study the animals' brains. The researchers were looking for changes to synapses.

"Stress is associated with a loss of synapses in this region of the brain that we think is important in depression," Liston says. And sure enough, the stressed-out mice lost a lot of synapses.

Next, the scientists gave the animals a dose of ketamine. And Liston says that's when they noticed something surprising. "Ketamine was actually restoring many of the exact same synapses in their exact same configuration that existed before the animal was exposed to chronic stress," he says.

In other words, the drug seemed to be repairing brain circuits that had been damaged by stress.

That finding suggested one way that ketamine could be relieving depression in people. But it didn't explain how ketamine could work so quickly.

Was the drug really creating all these new synapses in just a couple of hours?

To find out, the team used a technology that makes living brain cells glow under a microscope. "You can kind of imagine Van Gogh's Starry Night," Liston says. "The brain cells light up when they become active and become dimmer when they become inactive."

That allowed the team to identify brain circuits by looking for groups of brain cells that lit up together.

And that's when the scientists got another surprise.

After the mice got ketamine, it took less than six hours for the brain circuits damaged by stress to begin working better. The mice also stopped acting depressed in this time period.

But both of these changes took place long before the drug was able to restore many synapses.

"It wasn't until 12 hours after ketamine treatment that we really saw a big increase in the formation of new connections between neurons," Liston says.

The research suggests that ketamine triggers a two-step process that relieves depression.

First, the drug somehow coaxes faulty brain circuits to function better temporarily. Then it provides a longer-term fix by restoring the synaptic connections between cells in a circuit.

One possibility is that the synapses are restored spontaneously once the cells in a circuit begin firing in a synchronized fashion, says INSERM'S Beyeler, who wrote a commentary accompanying the study.

The new study suggests not only how ketamine works but also why its effects typically wear off after a few days or weeks, she says. "What we can imagine is that ketamine always has this short-term antidepressant effect, but then if the synaptic changes are not maintained, you will have relapse," Beyeler says.

If that's true, she says, scientists' next challenge is to find a way to maintain the brain circuits that ketamine has restored.