Bent By Nature - Ep. 2: Music Could Be Your Whole Life

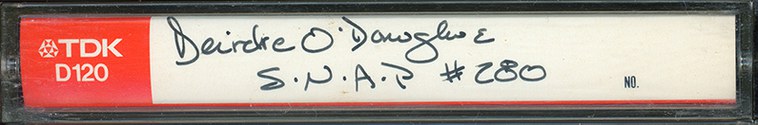

In episode two of Bent By Nature, co-producer Bob Carlson explores the life of influential and enigmatic DJ Deirdre O’Donoghue behind the mic. Born in New York City and DJing across the country before landing at KCRW to host "SNAP!", O’Donoghue didn’t talk much about her past or private life — even in the face of personal demons, and eventually, her deteriorating health.

But O’Donoghue’s fierce passion for music manifested in close friendships with those who came through her studio and beyond, from artists like Michael Stipe and Julian Cope, to record store owners, to young station volunteers she nurtured and mentored. Even amidst a kind of self-appointed solitude, O’Donoghue devoted herself to those she chose to let in, coming to the aid of artists in dire straits and offering solace within her record-filled apartment alongside a cup of tea and her cherished pet birds.

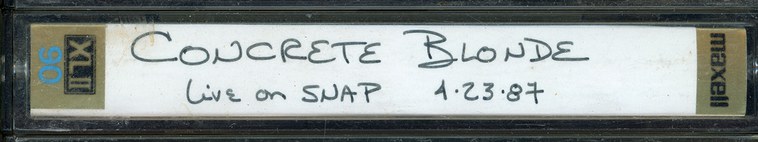

Her presence could, and did, change lives. Here, some of O’Donoghue’s closest friends, including Concrete Blonde’s Johnette Napolitano, Tricia Halloran, and the late Pat Fish of Jazz Butcher, reflect on O’Donoghue’s life away from the studio and the many stories they shared.

“No one knows this, it’s a little known fact, but Deirdre bailed me outta jail,” says Jonhnette Napolitano, vocalist and principal songwriter for Concrete Blonde.

In 1987, following a show at Santa Monica’s Texas Records, a barefoot and slip-clad Napolitano made a wrong turn on a one-way street and was immediately pulled over. She didn’t have her license or insurance, so she was arrested, and her Oldsmobile Cutlass was towed, though not before Napolitano managed to stash a joint in the ashtray under the seat. O’Donoghue, who attended the show, saw the musician being hauled away.

“I have $200 in a jar in the refrigerator at home,” she said. “I’ll bail you out.” And so, she did.

“I remember being lovingly searched by a very large police woman in front of very large police men ... and here comes Deirdre with her jar and her cash,” Napolitano recalls. “Wouldn't it be a bonding moment for you with anybody who bailed you out of jail? That definitely sealed the deal for me. Because not everybody does that for people. And we were very good friends after that.”

O’Donoghue always seemed to have a personal connection with the musicians who played on her program. And it made the interviews on “SNAP!” seem informal and intimate.

Read more: BBN Episode 1: This Is "SNAP!"

“She thought like a songwriter. She saw things like a songwriter and phrased things like a songwriter,” Napolitano says. “I had never been aware, until now, [of] how vulnerable I was in my writing. It was embarrassing, really. And if I had the sense to be embarrassed, which I never do, I think that’s probably what she did: understand and hear.

That's what connects with people when you're naked, and I didn't have the self-editing skills to know that I was even supposed to even do that at all. I was just like a faucet on full, all the fucking time. That's why she approached me from a self-care kind of place, like a warm blanket.”

That connectedness forged deep friendships with many, if not most, of the artists who came through her show.

“I have a phone book of hers, with names and numbers, and almost every band she played is in there,” says Tricia Halloran, who began as a volunteer on “SNAP!” and later became a KCRW DJ and one of O’Donoghue’s closest friends. “No band was off-limits to her. It could be Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins, it could be Michael Stipe of R.E.M., it could be the most unknown local band. She became best friends with all of them. By becoming friends with Vic Chesnutt, she became familiar with the Athens scene, and that's how the music scene was then: Everything was hand-to-hand.”

"Every scene needs that"

But these weren’t relationships of convenience. Off the air, O’Donoghue would be an anchor, helping many musicians during their darkest times. Among them was the late Pat Fish, a.k.a. Jazz Butcher.

“I was going through some fairly extreme, not just making my own life of misery, but making everybody else's life a misery. I was having a little episode,” he recalls. “[We] started talking on the phone, Deirdre and me, and she was a little rock. She really, really helped my brain.”

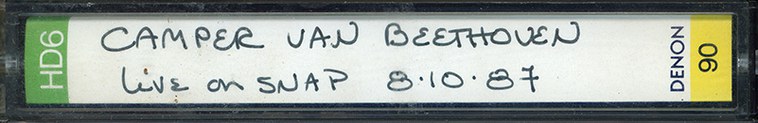

Artists like David Lowery, of Camper Van Beethoven and Cracker, would call her out of the blue every once in a while, just to talk about music or the business, their personal lives, and things going on. They didn’t always have a reason why.

Beethoven and Cracker, would call her out of the blue every once in a while, just to talk about music or the business, their personal lives, and things going on. They didn’t always have a reason why.

“I have two older sisters, and in a way, she always looked like she'd be part of our family,” Lowery says. “Maybe it was something subconscious like that, you know. But she became like a big sister to me.”

But she also made friends with non-musicians.

Michael Meister, who co-owned Texas Records in Santa Monica — which later became the small but influential record label Texas Hotel Records — became a close friend and major influence on O’Donoghue’s musical taste after she paid a visit to his store.

“In walks this woman, very unassuming. If I was gonna really profile her, I would say there’s nothing in the store that she's interested in,” Meister says. “And she came up with all these records, these Australian bands like the Laughing Clowns and the Triffids ... and she goes, ‘I want to get these,” and when she opened her mouth, I said, ‘You're Deirdre O’Donoghue.’ I knew her voice ... So we just started talking, and from there it blossomed out and we became truly great friends over this love of music. That is the uniqueness of Deirdre: She made you family. And that was really important.”

"She made you family. And that was really important.”

![texas records moving postcard 1986 [via Dave + Bekki Newton].jpg texas records moving postcard 1986 [via Dave + Bekki Newton].jpg](https://www.kcrw.com/music/shows/bent-by-nature/music-could-be-your-whole-life/texas-records-moving-postcard-1986-via-dave-bekki-newton.jpg/@@images/751ec872-cd56-443d-81f6-5f038e000146.jpeg) In Bob Carlson’s early years at KCRW, he was a young recording engineer, and recorded most of the performances during the final years of “SNAP!.” And O’Donoghue made him a part of the “SNAP!” world as a sign of respect and appreciation.

In Bob Carlson’s early years at KCRW, he was a young recording engineer, and recorded most of the performances during the final years of “SNAP!.” And O’Donoghue made him a part of the “SNAP!” world as a sign of respect and appreciation.

“I was such a nerd, straight-arrow at the time, so Deirdre gave me a persona to lend me an air of dangerous mystery: Bob Carlson of Carlson Chemical Industries,” he recalls. “She had a tight group of friends who all must have felt like me, a little honored to be in her inner circle.”

And if you were, she might invite you over to her Santa Monica apartment, a basic, rent-controlled, one-bedroom abode transformed by draped fabric, scarves over lights, and walls of well-organized CDs that imbued the space with an air of magic.

“She would [be] working on something [with] stuff laying around, but she knew where everything was,” Halloran says. “And she had two little birds in a bird cage. I think birds came and went, but there was usually a couple of them. She really cherished those birds. And she would say, ‘Do you want to come over and have tea with me and the birds?’ And she always had a pot of tea on the stove, and I would go over there and lounge around on some beanbag chair and listen to her expostulate about music. Those are very precious times.”

A girl from a thousand years ago

O'Donoghue didn’t talk about her past very much, even though it seemed she’d had traumas in her life, and that they still affected her. Sometimes she would even talk about it on the air, without actually talking about it.

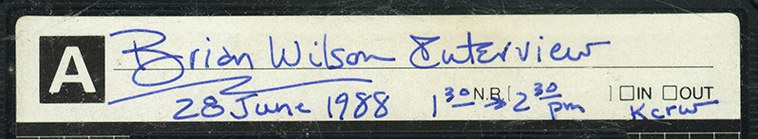

“Well there’s that difference between loneliness and solitude. I mean, I think there are times when you really feel alone. I enjoy the solitude. This is a philosophy, this is a way of life,” she confided to music legend Brian Wilson when he came into the “SNAP!” studio at KCRW for an interview in 1988.

Listen: Brian Wilson on "SNAP!" (6/28/1988)

“She was a very feeling person,” says journalist and musician Robert Lloyd. “She was just this Irish girl from a thousand years ago, somehow. I didn't know what her thoughts were about deeper things. But you could tell that she felt a lot of things.”

O’Donoghue’s sister Teri shared a few fragments of Deirdre’s life with us via email. She was born in New York City, the oldest of eight children: six girls and two boys. It was such a big family that they never all lived in a house at the same time. Deirdre went to Catholic schools until she graduated high school. The family moved a few times: from New York to Ohio, then to Bucks County, Pennsylvania. O’Donoghue used to take several of the younger siblings to B-movies at the drive-in with the family station wagon. Teri remembers she once took them to see “Psycho.”

Teri O’Donoghue says that Deirdre was the first feminist she ever knew. Deirdre went to Clark University in Worcester, Mass. and worked for the school paper. She ran for class president against three guys, one of whom was the actor John Heard. Neither of them won the election. She graduated in 1968 with a degree in microbiology.

Teri O’Donoghue says that Deirdre was the first feminist she ever knew. Deirdre went to Clark University in Worcester, Mass. and worked for the school paper. She ran for class president against three guys, one of whom was the actor John Heard. Neither of them won the election. She graduated in 1968 with a degree in microbiology.

In her radio career, O’Donoghue worked in radio in Boston, Detroit, and Dallas. At one point, she was told to never play two women artists back to back, because people would change the station. Eventually she wound up at the legendary Pasadena experimental radio station KPPC, which at the time was the radio home of the satire group known as The Credibility Gap. That’s how comedian and voice artist Harry Shearer, who hosted “Le Show” on KCRW for nearly 30 years, met Deirdre.

“I think it was a sort of a happy time for her. She was starting to do what she loved, and was surrounded by people who were supportive and encouraging,” Shearer says. “She was just a wonderful, bright, intense, funny, sweet, and dark person. But she really epitomizes, to me, the height of the free or underground FM radio experience, as it relates to music.”

"She epitomizes, to me, the height of the free or underground FM radio experience.”

KCRW’s former Music Director, Tom Schnabel, remembers hearing Deirdre for the first time, on the commercial jazz stations KBCA 105.1.

“I'm listening one afternoon, and I hear an ECM record being played: ‘Old and New Dreams’ with Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, drummer Colin Walcott, and others. It was a typical ECM kinda visionary record,” Schnabel recalls.

“And I thought: ‘Who the heck is this? They never played this kind of music.’ And on comes this voiceover, someone who was really, really good.”

Not long after, Schnabel stopped hearing her on the air, so he tracked O’Donoghue down and gave her a show. Despite his best efforts, her first show was buried at an ungodly hour. But the audience responded anyway, and then-KCRW General Manager Ruth Hirschman gave O’Donoghue a coveted Saturday night time slot.

Read more: Brian Eno on "SNAP!" (5/8/82)

At first, “SNAP!” stood for “Saturday Night's A Party,” and later it became “Saturday Night Avant-Pop.” But once the show moved to weekdays, it was just “SNAP!” The program ran for nine years on KCRW, from 1982 until 1991. During that time, O’Donoghue changed KCRW and the sound of radio in LA. She inspired listeners and impacted lives. When Halloran started as a volunteer on “SNAP!” answering phones, she was working in the buttoned-up corporate world by day. But a life in music started to seem much more appealing, especially as she started spending more time with O’Donoghue.

“She gave me advice on how to negotiate and how to ask for things and how to be a creative person and still make a living for yourself in a man's world,” recalls Halloran, who was quite literally pushed into the DJ chair when O’Donoghue asked her to take over the show one night while she stepped out with her guest, Pere Ubu.

“I don't even think I thought I could be a DJ,” Halloran says. “She ... put the headphones on [me] and turned the mic on. That was my first time on the air. It definitely changed my entire life.” Halloran would go on to host her own DJ show on KCRW, “Brave New World,” for 15 years.

“It was very clear that she should escape”

By the beginning of the ‘90s, O’Donoghue had fought on-and-off battles with her bosses at KCRW. And at the same time, she started to develop health problems that coincided with remodeling work being done in the basement studios. She felt that there was something that was making her sick, so she asked if she could start doing her show from home.

KCRW GM Ruth Hirschman said it was not an option for “SNAP!” to be hosted remotely, while O’Donoghue insisted the basement wasn’t good for her health. She began to disappear for days, with little notice or explanation.

“It was sad, and it was sudden. And I think Ruth didn't fire her. I think Deirdre just quit,” Schnabel says. “Ruth had to find someone else and she brought me in to do that slot. I recall that the person answering the phones got a lot of hate calls: ‘Where's Deirdre? What's he doing on the air? What's going on?’ That kind of thing.”

After O’Donoghue left KCRW, she created a derivative version of “SNAP!” on San Diego’s commercial station, 91x, called “SNAP Judgements.” And she continued to do a Sunday morning version of her popular “Breakfast with the Beatles” show on an LA commercial radio station, a job which paid her bills even while she was at KCRW. And she still had a community of close friends spread out across the globe whom she would visit, reporting to Halloran via letters her tales of trips to the countryside with friends in the daytime and trysts with strangers at night.

After O’Donoghue left KCRW, she created a derivative version of “SNAP!” on San Diego’s commercial station, 91x, called “SNAP Judgements.” And she continued to do a Sunday morning version of her popular “Breakfast with the Beatles” show on an LA commercial radio station, a job which paid her bills even while she was at KCRW. And she still had a community of close friends spread out across the globe whom she would visit, reporting to Halloran via letters her tales of trips to the countryside with friends in the daytime and trysts with strangers at night.

In 1992, O’Donoghue also paid a visit to the home of singer, historian, and writer Julian Cope. She’d long played his music on “SNAP!,” and he was due to be one of her next scheduled guests when she quit the show. Now she turned up in his village of Yeatsbury in England.

“She was in a bad place, it was as though she knew that LA was killing her,” Cope says. “It was physically killing her, but also she knew that an urban environment was killing her. It was very clear that she should escape. So she ended up staying at our house.

Our house is a very peculiar place, and it's part of an old manor house. It's so ancient that it just allows you to divest yourself of any urban influence … Everybody who's come here has felt the same way. Because it just puts you in that mind. It's of a total other time.”

So O’Donoghue settled in the ancient village home of Julian Cope and his wife, along with a few other houseguests. Eventually, though, she headed back to her Santa Monica apartment.

So O’Donoghue settled in the ancient village home of Julian Cope and his wife, along with a few other houseguests. Eventually, though, she headed back to her Santa Monica apartment.

“I don't think Deirdre would have left if it wasn't for the fact that she didn't have future plans,” Cope says. “I think she knew that she had cooked up some good shit, and was gonna have to leave it on the stove for other people to finish it.”

Back home, her health problems continued.

“She was very sick. At one point, I remember saying, ‘Deirdre, you need to do something here. There's something wrong and you need to go to a doctor,’” Meister says. “And she wouldn't go until it was too late.”

O’Donoghue was eventually diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. She withdrew from many of her friends, going silent for stretches of time.

“I know well enough to say that she felt she was coming to a conclusion,” says Cope.

“I know well enough to say that she felt she was coming to a conclusion.”

One of O’Donoghue’s best friends during this time was artist Lawrence Bogle, who lived in London. Bogle was a cover artist for the record label Kitchenware Records, which was home to “SNAP!” favorites like Prefab Sprout, Hurrah!, Martin Stephenson and the Daintees, and more.

In order to avoid having to phone him, O’Donoghue bought Bogle a fax machine so she could write whatever was on her mind, and that’s how the two communicated. With a sharp mind and voracious appetite for books, O’Donoghue would tell him about what she’d read, along with her research on M.S. and healing. Bogle even learned how to do Reiki healing, and did a session with her. The two didn't talk about music at all; it was art, energies, and spirituality that captivated them. She was a pagan, and that interested Bogle.

“When I met her, she had arrived at a place where she was very grateful for lots of things, because she had endured a great deal at the hands of others,” he says. “And so she was very, very glass-half-full. Even when she faced great disappointment, she could see through to the other side of it.”

“When I met her, she had arrived at a place where she was very grateful for lots of things, because she had endured a great deal at the hands of others,” he says. “And so she was very, very glass-half-full. Even when she faced great disappointment, she could see through to the other side of it.”

Bogle was used to her intermittent silences and withdrawals. But she eventually ceased to respond completely, even despite his repeated requests for a reply.

“And then I was really worried that something was wrong. So for the first time, I called Tricia [Halloran] and asked her, could she go and find out? Could she knock on her door?” Bogle says. “And a couple days later, Tricia called me back and said ‘She's gone,’ you know. Terrible, terrible shock. Really bad.”

Deirdre O’Donoghue died on January 21, 2001. She was 52. The cause of death was never disclosed.

“I think another thing she showed me was that music could be your whole life,” Halloran says. “I would always come home and find an album or something she wanted me to hear, or a book, a little packet with a note: ‘I want to tell you about this band I heard,’ or ‘I've been listening to these new tapes, they're amazing.’ Or ‘I put together this Pat Fish show that I want you to come to.’

She lived music 24/7. It was such a huge part of her life. And it showed me that it could be my life, too.”