Bent By Nature - Ep. 6: Crossing Over (with David Lowery)

It’s New Year’s Eve, 1986. Deirdre is talking with the LA Times’ music critic, Robert Hilburn, about the musical trends of 1985.

Deirdre O’Donoghue: I don't think that the big, quote-unquote, "rock" stations can very much longer ignore the growing numbers of people who are listening to alternative radio stations all around the country ... with which you're seeing album sales, at least on a smaller level, but it's making a bump.

Among the acts Deirdre discovered that year was a crew of self-described “pot-smoking hippies from Santa Cruz.” Camper Van Beethoven lit up the college circuit in 1985 with their breakout single, “Take the Skinheads Bowling.” And they quickly became one of Deirdre’s firm favorites.

David Lowery is Camper Van Beethoven’s guitarist and de facto frontman. He explains that Deirdre’s show was just one taproot for a larger movement which was spreading across the country in the mid-’80s. In this episode of “Bent By Nature,” he shares how the band navigated their own transition from indie darlings to major-label recording artists.

David Lowery: In 1987, I was living in Santa Cruz, but we were going down to LA a lot, partly because it was a great place for us to play shows. Also, we had done an in-store very early on at Texas Records in Santa Monica. So, sometimes when we were in LA, there would be an in-store at Texas Records, and it was invariably some cool up-and-coming band. And I think I went to go see Downy Mildew, and I got introduced to Deirdre O'Donoghue, who, I was told, has a really cool radio show on KCRW.

Certainly, I remember going out with Deirdre and a couple other people before we were ever on "SNAP!" And she seemed to be around in the scene. She knew a lot of people that we knew. She was really highly respected. And I started listening to KCRW, and oftentimes her show, when I was driving around in Los Angeles.

O’Donoghue: Time’s not tight. Time is right. I’m so happy to have this group here. I’ve been looking forward to this ensemble for a while. David is touching the microphone gently. And it’s my pleasure to welcome to “SNAP!” and KCRW: Camper Van Beethoven. Hi guys.

Lowery: Hi. Except our drummer couldn’t be here ‘cause he’s in jail, but we’re gonna tell you some more about that a little later. So we don’t have a drummer tonight, and we’re going to do a little acoustic set. We’re kinda used to it. He’s always in and out of jail, y’know. 15 countries all around the world, passport hassles, y’know, alimony and all this stuff.

O’Donoghue: Well, tonight’s the night we can tell the tales of Chris Pedersen.

Lowery: OK, well, this first song we’d like to do is a traditional Camper Van Beethoven song.

Victor Krummenacher [bassist]: Chris, out in that cell in South Pasadena, we miss you, Chris.

![[706] SNAP #524 with Camper Van Beethoven Live - 8-10-87.jpeg](https://www.kcrw.com/music/shows/bent-by-nature/crossing-over-with-camper-van-beethoven/706-snap-524-with-camper-van-beethoven-live-8-10-87.jpeg/@@images/ac0623fe-6ed1-46bd-abc3-0e40933097dd.jpeg)

The poor people who first heard us on that first show, when we're talking about how our drummer's in jail ... He's not in jail, he just wasn't there. So we say "He's in jail," right? And, I was like, "These poor people, they have no idea what's true and what's not true when they're listening to us." But she doesn't correct us when we say things like "Our drummer's in jail" and stuff like that. She just lets us do it. Someplace else, somebody would have been like, "Whoa, you're on your own there. Your drummer's not really in jail, are they?" Or they would have said something to undermine it, and she didn't.

O’Donoghue: Jonathan Segal, Victor Krummenacher, Greg Lisher, and David Lowery of Camper Van Beethoven. We're missing Chris Pedersen. Let’s tell some stories about Chris Pedersen.

Krummenacher: Well, see, we were going to Carrows the other night in South Pasadena, and…

Lowery: ...see, Chris likes to go to Carrows and order pancakes in the middle of the night. But he doesn't eat pancakes. He just likes to eat the syrup.

Krummenacher: He likes to lap the syrup up off the plate.

Lowery: Like, a whole box of it. He'll just stay up all night and eat syrup.

Krummenacher: But anyhow, we were going to South Pasadena and Chris, like … I don't know what came over him, but he stole a ‘67 Barracuda and started driving down the road. We were kind of like, “Well, that's kinda uncool, Chris.” But anyhow, we're driving down the road and the cops pulled us over, and they took him out and they searched him, held him upside down.

Lowery: OK, so this next song we're gonna play is a song of great enduring strength and beauty. It’s from our upcoming LP on IRS Records. (Laughs)

IRS Records — which was R.E.M.'s label, and was kind of the "cool major" — wanted to sign us. And there was this vote in the band, and everybody but me voted against it. But I was getting this inkling that, in a way, we weren't really this niche thing. We weren't mainstream, but we were somewhere in between the niche movement that was punk rock and underground, more experimental stuff, and the more mainstream stuff. We were starting to get a lot of people at our shows already — in some places, close to a thousand people. To me, selling out was how you sounded. And if you could go to a major label and have artistic control, why wouldn't you do that? So it took until 1987 for the whole band to feel comfortable that we could "sell out," as it were, and get a major-label deal and do a record.

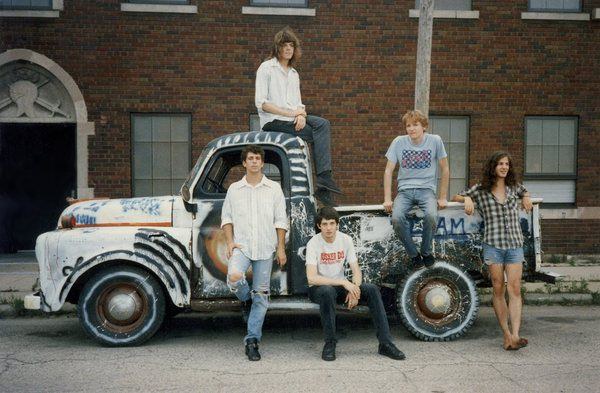

Camper Van Beethoven in 1986. Photo courtesy of the artist.

O’Donoghue: Here's the question of the day. Are you, in fact, prepared to sell out, gentlemen?

Lowery: I don't know if people understood this, but we've always been trying to sell out our entire life, our entire career. We thought we were making completely commercial pop music the whole time. We're still making the same kind of music, actually. It’s exactly the same kind of music, but. We’ve always been trying to sell out, man. We want to, like, have brands of jeans named after us. We want a brand of acid named after us. We actually sold our souls to the Devil. I don’t think we signed to a record company, we sold our souls to the devil, OK? Come on. It’s a great deal. [1987-08-10]

The interesting thing about that time, that I think is lost on a lot of people, is that it was called the indie movement not because we were bound together stylistically, but because we literally used an alternate distribution promotion system to what was then the mainstream: major-label distribution, chain record stores, commercial radio. Sometime in the early '80s, the punk bands first pioneered this. But then the indie bands, the non-punk bands, began to use the same system. The system was a series of college radio stations that basically played new stuff by non-major label artists. It was a network of independent distributors. And there were independent record stores.

So in San Francisco, you had a number of indie clubs and a number of indie radio stations, and they all overlapped personnel and stuff a lot, so promoting to one kinda helped you with the other. So doing a show at the Mabuhay Gardens, maybe they got you on to KUSF or KALX to do an interview, and then the stores had your record. This was replicated all over the country. You had essentially the same thing in San Diego, you had the same thing in Tucson, you had the same thing in Austin, Texas. Same thing in Portland, Oregon, or Eugene, Oregon. Everywhere, all around the country, almost instantaneously. And so that’s what we’re tapping into when we started, and that’s where punk-rock broadens out, taps into this indie network, and we just follow right in it.

I remember it was a little controversial when we went to Virgin Records, but Virgin Records was originally an independent label. And when I grew up, Virgin Records put out really weird records, mostly prog-rock and stuff like that. So Virgin had this cachet that the other [majors didn’t]. Even though it was independent when we first signed to them, it ran through the major label system. And they had big, big stars. So, I guess we were selling out, but it's kind of a quirky person's label to sign a contract with. Maybe it was the beginning of "hip capitalism" or something like that.

O’Donoghue: Camper Van Beethoven, playing live on “SNAP!” tonight, this night of a very full moon. Big harvest moon out there. 14 September 1989.

Lowery: Oh good.

O’Donoghue: Why don’t you do “Pictures of Matchstick Men?”

Lowery: No, no. We don’t have to. This is public radio. [Laughter]

So in that session, we're asked to play "Pictures Of Matchstick Men." And we say "No, we don't have to." Because we originally recorded that song for the "Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart" sessions. And then we come to "Key Lime Pie," and the radio department says, “There's not really a radio hit here. So why don't we revisit 'Pictures of Matchstick Men?' Because you liked that song."

![[259] Camper Van Beethoven - 14 September 1989.jpeg](https://www.kcrw.com/music/shows/bent-by-nature/crossing-over-with-camper-van-beethoven/259-camper-van-beethoven-14-september-1989.jpeg/@@images/5181c097-0663-4ce0-a1df-c38631669701.jpeg)

And we were really stuck in a hard place, ‘cause we were like ... "Well, okay, all right." So at that point, we were probably like, "That is a song for commercial radio. It has been made plain to us by everybody who works with us that we did that song, we made it fit in with this record, for commercial radio. So that's all people are going to hear from this record for a while, right? So we're not going to play it." But we're also speaking to what “SNAP!” was. I mean, it was the alternative to KROQ and those other commercial, alternative, modern-rock radio stations, whatever they were called then.

Camper Van Beethoven broke up, so I went back to LA and stayed with our manager so I could sort out my record deal, or what I was doing with the band. And I only really knew a few people in LA that weren't heavily connected to the Camper Van Beethoven family of people, and I didn't really want to deal with any of those people. So at some point, I called up Deirdre and I think we went and hung out, and she asked me to come on and guest DJ the show, and I did.

I was totally a lost soul at that point. And it was very nice that she brought me in to guest DJ a show, because I think actually it helped increase my status in my record label's eyes. And they exercised the "key leaving member clause," which sounds really great on one level, 'cause you're like, "Hey, I get the recording contract." But you also get the previous band's debt. So I'm hearing from the Camper guys indirectly through the grapevine that they're pissed off that I got the contract. But I'm like, "I got the debt! I got the debt!"

Between Cracker and Camper, I ended up calling her a lot, personally calling her up and going, "Hey, this is what's going on. What do you think?" I don't remember if it was before Camper broke up or after Jonathan [Segel] left. Between "Our Revolutionary Sweetheart" and "Key Lime Pie," there were a lot of things I had to think about -- the record label and the business and musically -- and then [I was] going into Cracker. So I'd call her out of the blue every once in a while and we would talk about music or the business, our lives, personal lives, things that were going on. I don't know why. I mean, I have two older sisters. In a way, she always kind of looked like she'd be part of our family. Maybe it was something subconscious like that. I don't know. But she was kind of like a big sister to me.

===

David Lowery is now a Senior Lecturer in the Music Business at the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business. He still performs with both Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven. He released his most recent solo album, “Leaving Key Member Clause,” in 2021.