excerpt

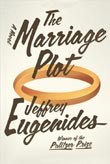

The Marriage Plot

The Marriage Plot

By Jeffrey Eugenides

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Copyright © 2011 Jeffrey EugenidesAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780374203054

Marriage Plot, The

A Madman in Love

To start with, look at all the books. There were her Edith Wharton novels, arranged not by title but date of publication; there was the complete Modern Library set of Henry James, a gift from her father on her twenty-first birthday; there were the dog-eared paperbacks assigned in her college courses, a lot of Dickens, a smidgen of Trollope, along with good helpings of Austen, George Eliot, and the redoubtable Brontë sisters. There were a whole lot of black-and-white New Directions paperbacks, mostly poetry by people like H.D. or Denise Levertov. There were the Colette novels she read on the sly. There was the first edition of Couples, belonging to her mother, which Madeleine had surreptitiously dipped into back in sixth grade and which she was using now to provide textual support in her English honors thesis on the marriage plot. There was, in short, this mid-size but still portable library representing pretty much everything Madeleine had read in college, a collection of texts, seemingly chosen at random, whose focus slowly narrowed, like a personality test, a sophisticated one you couldn't trick by anticipating the implications of its questions and finally got so lost in that your only recourse was to answer the simple truth. And then you waited for the result, hoping for "Artistic," or "Passionate," thinking you could live with "Sensitive," secretly fearing "Narcissistic" and "Domestic," but finally being presented with an outcome that cut both ways and made you feel different depending on the day, the hour, or the guy you happened to be dating: "Incurably Romantic."

These were the books in the room where Madeleine lay, with a pillowover her head, on the morning of her college graduation. She'd read each and every one, often multiple times, frequently underlining passages, but that was no help to her now. Madeleine was trying to ignore the room and everything in it. She was hoping to drift back down into the oblivion where she'd been safely couched for the last three hours. Any higher level of wakefulness would force her to come to grips with certain disagreeable facts: for instance, the amount and variety of the alcohol she'd imbibed last night, and the fact that she'd gone to sleep with her contacts in. Thinking about such specifics would, in turn, call to mind the reasons she'd drunk so much in the first place, which she definitely didn't want to do. And so Madeleine adjusted her pillow, blocking out the early morning light, and tried to fall back to sleep.

But it was useless. Because right then, at the other end of her apartment, the doorbell began to ring.

Early June, Providence, Rhode Island, the sun up for almost two hours already, lighting up the pale bay and the smokestacks of the Narragansett Electric factory, rising like the sun on the Brown University seal emblazoned on all the pennants and banners draped up over campus, a sun with a sagacious face, representing knowledge. But this sun--the one over Providence--was doing the metaphorical sun one better, because the founders of the university, in their Baptist pessimism, had chosen to depict the light of knowledge enshrouded by clouds, indicating that ignorance had not yet been dispelled from the human realm, whereas the actual sun was just now fighting its way through cloud cover, sending down splintered beams of light and giving hope to the squadrons of parents, who'd been soaked and frozen all weekend, that the unseasonable weather might not ruin the day's festivities. All over College Hill, in the geometric gardens of the Georgian mansions, the magnolia-scented front yards of Victorians, along brick sidewalks running past black iron fences like those in a Charles Addams cartoon or a Lovecraft story; outside the art studios at the Rhode Island School of Design, where one painting major, having stayed up all night to work, was blaring Patti Smith; shining off the instruments (tuba and trumpet, respectively) of the two members of the Brown marching band who had arrived early at the meeting point and were nervously looking around, wondering where everyone else was; brightening the cobblestone side streets that led downhill to the polluted river, the sun was shining onevery brass doorknob, insect wing, and blade of grass. And, in concert with the suddenly flooding light, like a starting gun for all the activity, the doorbell in Madeleine's fourth-floor apartment began, clamorously, insistently, to ring.

The pulse reached her less as a sound than as a sensation, an electric shock shooting up her spine. In one motion Madeleine tore the pillow off her head and sat up in bed. She knew who was ringing the buzzer. It was her parents. She'd agreed to meet Alton and Phyllida for breakfast at 7:30. She'd made this plan with them two months ago, in April, and now here they were, at the appointed time, in their eager, dependable way. That Alton and Phyllida had driven up from New Jersey to see her graduate, that what they were here to celebrate today wasn't only her achievement but their own as parents, had nothing wrong or unexpected about it. The problem was that Madeleine, for the first time in her life, wanted no part of it. She wasn't proud of herself. She was in no mood to celebrate. She'd lost faith in the significance of the day and what the day represented.

She considered not answering. But she knew that if she didn't answer, one of her roommates would, and then she'd have to explain where she'd disappeared to last night, and with whom. Therefore, Madeleine slid out of the bed and reluctantly stood up.

This seemed to go well for a moment, standing up. Her head felt curiously light, as if hollowed out. But then the blood, draining from her skull like sand from an hourglass, hit a bottleneck, and the back of her head exploded in pain.

In the midst of this barrage, like the furious core from which it emanated, the buzzer erupted again.

She came out of her bedroom and stumbled in bare feet to the intercom in the hall, slapping the SPEAK button to silence the buzzer.

"Hello?"

"What's the matter? Didn't you hear the bell?" It was Alton's voice, as deep and commanding as ever, despite the fact that it was issuing from a tiny speaker.

"Sorry," Madeleine said. "I was in the shower."

"Likely story. Will you let us in, please?"

Madeleine didn't want to. She needed to wash up first.

"I'm coming down," she said.

This time, she held down the SPEAK button too long, cutting off Alton's response. She pressed it again and said, "Daddy?" but while she was speaking, Alton must have been speaking, too, because when she pressed LISTEN all that came through was static.

Madeleine took this pause in communications to lean her forehead against the door frame. The wood felt nice and cool. The thought struck her that, if she could keep her face pressed against the soothing wood, she might be able to cure her headache, and if she could keep her forehead pressed against the door frame for the rest of the day, while somehow still being able to leave the apartment, she might make it through breakfast with her parents, march in the commencement procession, get a diploma, and graduate.

She lifted her face and pressed SPEAK again.

"Daddy?"

But it was Phyllida's voice that answered. "Maddy? What's the matter? Let us in."

"My roommates are still asleep. I'm coming down. Don't ring the bell anymore."

"We want to see your apartment!"

"Not now. I'm coming down. Don't ring."

She took her hand from the buttons and stood back, glaring at the intercom as if daring it to make a sound. When it didn't, she started back down the hall. She was halfway to the bathroom when her roommate Abby emerged, blocking the way. She yawned, running a hand through her big hair, and then, noticing Madeleine, smiled knowingly.

"So," Abby said, "where did you sneak off to last night?"

"My parents are here," Madeleine said. "I have to go to breakfast."

"Come on. Tell me."

"There's nothing to tell. I'm late."

"How come you're wearing the same clothes, then?"

Instead of replying, Madeleine looked down at herself. Ten hours earlier, when she'd borrowed the black Betsey Johnson dress from Olivia, Madeleine had thought it looked good on her. But now the dress felt hot and sticky, the fat leather belt looked like an S&M restraint, and there was a stain near the hem that she didn't want to identify.

Abby, meanwhile, had knocked on Olivia's door and entered. "So much for Maddy's broken heart," she said. "Wake up! You've got to see this."

The path to the bathroom was clear. Madeleine's need for a shower was extreme, almost medical. At a minimum, she had to brush her teeth. But Olivia's voice was audible now. Soon Madeleine would have two roommates interrogating her. Her parents were liable to start ringing again any minute. As quietly as possible, she inched back down the hall. She stepped into a pair of loafers left by the front door, crushing the heels flat as she caught her balance, and escaped into the outer corridor.

The elevator was waiting at the end of the floral runner. Waiting, Madeleine realized, because she'd failed to close the sliding gate when she'd staggered out of the thing a few hours earlier. Now she shut the gate securely and pressed the button for the lobby, and with a jolt the antique contraption began to descend through the building's interior gloom.

Madeleine's building, a Neo-Romanesque castle called the Narragansett that wrapped around the plunging corner of Benefit Street and Church Street, had been built at the turn of the century. Among its surviving period details--the stained-glass skylight, the brass wall sconces, the marble lobby--was the elevator. Made of curving metal bars like a giant birdcage, the elevator miraculously still functioned, but it moved slowly, and as the car dropped, Madeleine took the opportunity to make herself more presentable. She ran her hands through her hair, finger-combing it. She polished her front teeth with her index finger. She rubbed mascara crumbs from her eyes and moistened her lips with her tongue. Finally, passing the balustrade on the second floor, she checked her reflection in the small mirror attached to the rear panel.

One of the nice things about being twenty-two, or about being Madeleine Hanna, was that three weeks of romantic anguish, followed by a night of epic drinking, didn't do much visible damage. Except for puffiness around her eyes, Madeleine looked like the same pretty, dark-haired person as usual. The symmetries of her face--the straight nose, the Katharine Hepburn-ish cheekbones and jawline--were almost mathematical in their precision. Only the slight furrow in her brow gave evidence of the slightly anxious person that Madeleine felt herself, intrinsically, to be.

She could see her parents waiting below. They were trapped between the lobby door and the door to the street, Alton in a seersucker jacket, Phyllida in a navy suit and matching gold-buckled purse. For a second, Madeleine had an impulse to stop the elevator and leave her parentsstuck in the foyer amid all the college-town clutter--the posters for New Wave bands with names like Wretched Misery or the Clits, the pornographic Egon Schiele drawings by the RISD kid on the second floor, all the clamorous Xeroxes whose subtext conveyed the message that the wholesome, patriotic values of her parents' generation were now on the ash heap of history, replaced by a nihilistic, post-punk sensibility that Madeleine herself didn't understand but was perfectly happy to scandalize her parents by pretending that she did--before the elevator stopped in the lobby and she slid open the gate and stepped out to meet them.

Alton was first through the door. "Here she is!" he said avidly. "The college graduate!" In his net-charging way, he surged forward to seize her in a hug. Madeleine stiffened, worried that she smelled of alcohol or, worse, of sex.

"I don't know why you wouldn't let us see your apartment," Phyllida said, coming up next. "I was looking forward to meeting Abby and Olivia. We'd love to treat them to dinner later."

"We're not staying for dinner," Alton reminded her.

"Well, we might. That depends on Maddy's schedule."

"No, that's not the plan. The plan is to see Maddy for breakfast and then leave after the ceremony."

"Your father and his plans," Phyllida said to Madeleine. "Are you wearing that dress to the ceremony?"

"I don't know," Madeleine said.

"I can't get used to these shoulder pads all the young women are wearing. They're so mannish."

"It's Olivia's."

"You look pretty whacked out, Mad," Alton said. "Big party last night?"

"Not really."

"Don't you have anything of your own to wear?" Phyllida said.

"I'll have my robe on, Mummy," Madeleine said, and, to forestall further inspection, headed past them through the foyer. Outside, the sun had lost its battle with the clouds and vanished. The weather looked not much better than it had all weekend. Campus Dance, on Friday night, had been more or less rained out. The Baccalaureate service on Sunday had proceeded under a steady drizzle. Now, on Monday, the rainhad stopped, but the temperature felt closer to St. Patrick's than to Memorial Day.

As she waited for her parents to join her on the sidewalk, it occurred to Madeleine that she hadn't had sex, not really. This was some consolation.

"Your sister sends her regrets," Phyllida said, coming out. "She has to take Richard the Lionhearted for an ultrasound today."

Richard the Lionhearted was Madeleine's nine-week-old nephew. Everyone else called him Richard.

"What's the matter with him?" Madeleine asked.

"One of his kidneys is petite, apparently. The doctors want to keep an eye on it. If you ask me, all these ultrasounds do is find things to worry about."

"Speaking of ultrasounds," Alton said, "I need to get one on my knee."

Phyllida paid no attention. "Anyway, Allie's devastated not to see you graduate. As is Blake. But they're hoping you and your new beau might visit them this summer, on your way to the Cape."

You had to stay alert around Phyllida. Here she was, ostensibly talking about Richard the Lionhearted's petite kidney, and already she'd managed to move the subject to Madeleine's new boyfriend, Leonard (whom Phyllida and Alton hadn't met), and to Cape Cod (where Madeleine had announced plans to cohabitate with him). On a normal day, when her brain was working, Madeleine would have been able to keep one step ahead of Phyllida, but this morning the best she could manage was to let the words float past her.

Fortunately, Alton changed the subject. "So, where do you recommend for breakfast?"

Madeleine turned and looked vaguely down Benefit Street. "There's a place this way."

She started shuffling along the sidewalk. Walking--moving--seemed like a good idea. She led them past a line of quaint, nicely maintained houses bearing historical placards, and a big apartment building with a gable roof. Providence was a corrupt town, crime-ridden and mob-controlled, but up on College Hill this was hard to see. The sketchy downtown and dying or dead textile mills lay below, in the grim distance.Here the narrow streets, many of them cobblestone, climbed past mansions or snaked around Puritan graveyards full of headstones as narrow as heaven's door, streets with names like Prospect, Benevolent, Hope, and Meeting, all of them feeding into the arboreous campus at the top. The sheer physical elevation suggested an intellectual one.

"Aren't these slate sidewalks lovely," Phyllida said as she followed along. "We used to have slate sidewalks on our street. They're much more attractive. But then the borough replaced them with concrete."

"Assessed us for the bill, too," Alton said. He was limping slightly, bringing up the rear. The right leg of his charcoal trousers was swelled from the knee brace he wore on and off the tennis court. Alton had been club champion in his age group for twelve years running, one of those older guys with a sweatband ringing a balding crown, a choppy forehand, and absolute murder in his eyes. Madeleine had been trying to beat Alton her entire life without success. This was even more infuriating because she was better than he was, at this point. But whenever she took a set from Alton he started intimidating her, acting mean, disputing calls, and her game fell apart. Madeleine was worried that there was something paradigmatic in this, that she was destined to go through life being cowed by less capable men. As a result, Madeleine's tennis matches against Alton had assumed such outsize personal significance for her that she got tight whenever she played him, with predictable results. And Alton still gloated when he won, still got all rosy and jiggly, as if he'd bested her by sheer talent.

At the corner of Benefit and Waterman, they crossed behind the white steeple of First Baptist Church. In preparation for the ceremony, loudspeakers had been set up on the lawn. A man wearing a bow tie, a dean-of-students-looking person, was tensely smoking a cigarette and inspecting a raft of balloons tied to the churchyard fence.

By now Phyllida had caught up to Madeleine, taking her arm to negotiate the uneven slate, which was pushed up by the roots of gnarled plane trees that lined the curb. As a little girl, Madeleine had thought her mother pretty, but that was a long time ago. Phyllida's face had gotten heavier over the years; her cheeks were beginning to sag like those of a camel. The conservative clothes she wore--the clothes of a philanthropist or lady ambassador--had a tendency to conceal her figure. Phyllida'shair was where her power resided. It was expensively set into a smooth dome, like a band shell for the presentation of that long-running act, her face. For as long as Madeleine could remember, Phyllida had never been at a loss for words or shy about a point of etiquette. Among her friends Madeleine liked to make fun of her mother's formality, but she often found herself comparing other people's manners unfavorably with Phyllida's.

And right now Phyllida was looking at Madeleine with the proper expression for this moment: thrilled by the pomp and ceremony, eager to put intelligent questions to any of Madeleine's professors she happened to meet, or to trade pleasantries with fellow parents of graduating seniors. In short, she was available to everyone and everything and in step with the social and academic pageantry, all of which exacerbated Madeleine's feeling of being out of step, for this day and the rest of her life.

She plunged on, however, across Waterman Street, and up the steps of Carr House, seeking refuge and coffee.

The café had just opened. The guy behind the counter, who was wearing Elvis Costello glasses, was rinsing out the espresso machine. At a table against the wall, a girl with stiff pink hair was smoking a clove cigarette and reading Invisible Cities. "Tainted Love" played from the stereo on top of the refrigerator.

Phyllida, holding her handbag protectively against her chest, had paused to peruse the student art on the walls: six paintings of small, skin-diseased dogs wearing bleach-bottle collars.

"Isn't this fun?" she said tolerantly.

"La Bohème," Alton said.

Madeleine installed her parents at a table near the bay window, as far away from the pink-haired girl as possible, and went up to the counter. The guy took his time coming over. She ordered three coffees--a large for her--and bagels. While the bagels were being toasted, she brought the coffees over to her parents.

Alton, who couldn't sit at the breakfast table without reading, had taken a discarded Village Voice from a nearby table and was perusing it. Phyllida was staring overtly at the girl with pink hair.

"Do you think that's comfortable?" she inquired in a low voice.

Madeleine turned to see that the girl's ragged black jeans were held together by a few hundred safety pins.

"I don't know, Mummy. Why don't you go ask her?"

"I'm afraid of getting poked."

"According to this article," Alton said, reading the Voice, "homosexuality didn't exist until the nineteenth century. It was invented. In Germany."

The coffee was hot, and lifesavingly good. Sipping it, Madeleine began to feel slightly less awful.

After a few minutes, she went up to get the bagels. They were a little burned, but she didn't want to wait for new ones, and so brought them back to the table. After examining his with a sour expression, Alton began scraping it punitively with a plastic knife.

Phyllida asked, "So, are we going to meet Leonard today?"

"I'm not sure," Madeleine said.

"Anything you want us to know about?"

"No."

"Are you two still planning to live together this summer?"

By this time Madeleine had taken a bite of her bagel. And since the answer to her mother's question was complicated--strictly speaking, Madeleine and Leonard weren't planning on living together, because they'd broken up three weeks ago; despite this fact, however, Madeleine hadn't given up hope of a reconciliation, and seeing as she'd spent so much effort getting her parents used to the idea of her living with a guy, and didn't want to jeopardize that by admitting that the plan was off--she was relieved to be able to point at her full mouth, which prevented her from replying.

"Well, you're an adult now," Phyllida said. "You can do what you like. Though, for the record, I have to say that I don't approve."

"You've already gone on record about that," Alton broke in.

"Because it's still a bad idea!" Phyllida cried. "I don't mean the propriety of it. I'm talking about the practical problems. If you move in with Leonard--or any young man--and he's the one with the job, then you begin at a disadvantage. What happens if you two don't get along? Where are you then? You won't have any place to live. Or anything to do."

That her mother was correct in her analysis, that the predicamentPhyllida warned Madeleine about was exactly the predicament she was already in, didn't motivate Madeleine to register agreement.

"You quit your job when you met me," Alton said to Phyllida.

"That's why I know what I'm talking about."

"Can we change the subject?" Madeleine said at last, having swallowed her food.

"Of course we can, sweetheart. That's the last I'll say about it. If your plans change, you can always come home. Your father and I would love to have you."

"Not me," Alton said. "I don't want her. Moving back home is always a bad idea. Stay away."

"Don't worry," Madeleine said. "I will."

"The choice is yours," Phyllida said. "But if you do come home, you could have the loft. That way you can come and go as you like."

To her surprise, Madeleine found herself contemplating this proposal. Why not tell her parents everything, curl up in the backseat of the car, and let them take her home? She could move into her old bedroom, with the sleigh bed and the Madeline wallpaper. She could become a spinster, like Emily Dickinson, writing poems full of dashes and brilliance, and never gaining weight.

Phyllida brought her out of this reverie.

"Maddy?" she said. "Isn't that your friend Mitchell?"

Madeleine wheeled in her seat. "Where?"

"I think that's Mitchell. Across the street."

In the churchyard, sitting Indian-style in the freshly mown grass, Madeleine's "friend" Mitchell Grammaticus was indeed there. His lips were moving, as if he was talking to himself.

"Why don't you invite him to join us?" Phyllida said.

"Now?"

"Why not? I'd love to see Mitchell."

"He's probably waiting for his parents," Madeleine said.

Phyllida waved, despite the fact that Mitchell was too far away to notice.

"What's he doing sitting on the ground?" Alton asked.

The three Hannas stared across the street at Mitchell in his half-lotus.

"Well, if you're not going to ask him, I will," Phyllida finally said.

"O.K.," Madeleine said. "Fine. I'll go ask him."

The day was getting warmer, but not by much. Black clouds were massing in the distance as Madeleine came down the steps of Carr House and crossed the street into the churchyard. Someone inside the church was testing the loudspeakers, fussily repeating, "Sussex, Essex, and Kent. Sussex, Essex, and Kent." A banner draped over the church entrance read "Class of 1982." Beneath the banner, in the grass, was Mitchell. His lips were still moving silently, but when he noticed Madeleine approaching they abruptly stopped.

Madeleine remained a few feet away.

"My parents are here," she informed him.

"It's graduation," Mitchell replied evenly. "Everyone's parents are here."

"They want to say hello to you."

At this Mitchell smiled faintly. "They probably don't realize you're not speaking to me."

"No, they don't," Madeleine said. "And, anyway, I am. Now. Speaking to you."

"Under duress or as a change of policy?"

Madeleine shifted her weight, wrinkling her face unhappily. "Look. I'm really hungover. I barely slept last night. My parents have been here about ten minutes and they're already driving me crazy. So if you could just come over and say hello, that would be great."

Mitchell's large emotional eyes blinked twice. He was wearing a vintage gabardine shirt, dark wool pants, and beat-up wingtips. Madeleine had never seen him in shorts or tennis shoes.

"I'm sorry," he said. "About what happened."

"Fine," Madeleine said, looking away. "It doesn't matter."

"I was just being my usual vile self."

"So was I."

They were quiet a moment. Madeleine felt Mitchell's eyes on her, and she crossed her arms over her chest.

What had happened was this: one night the previous December, in a state of anxiety about her romantic life, Madeleine had run into Mitchell on campus and brought him back to her apartment. She'd needed male attention and had flirted with him, without entirely admitting it to herself.In her bedroom, Mitchell had picked up a jar of deep-heating gel on her desk, asking what it was for. Madeleine had explained that people who were athletic sometimes got sore muscles. She understood that Mitchell might not have experienced this phenomenon, seeing as all he did was sit in the library, but he should take her word for it. At that point, Mitchell had come up behind her and wiped a gob of heating gel behind her ear. Madeleine jumped up, shouting at Mitchell, and wiped the gunk off with a T-shirt. Though she was within her rights to be angry, Madeleine also knew (even at the time) that she was using the incident as a pretext for getting Mitchell out of her bedroom and for covering up the fact that she'd been flirting with him in the first place. The worst part of the incident was how stricken Mitchell had looked, as if he'd been about to cry. He kept saying he was sorry, he was just joking around, but she ordered him to leave. In the following days, replaying the incident in her mind, Madeleine had felt worse and worse about it. She'd been on the verge of calling Mitchell to apologize when she'd received a letter from him, a highly detailed, cogently argued, psychologically astute, quietly hostile four-page letter, in which he called her a "cocktease" and claimed that her behavior that night had been "the erotic equivalent of bread and circus, with just the circus." The next time they'd run into each other, Madeleine had acted as if she didn't know him, and they hadn't spoken since.

Now, in the churchyard of First Baptist, Mitchell looked up at her and said, "O.K. Let's go say hello to your parents."

Phyllida was waving as they came up the steps. In the flirtatious voice she reserved for her favorite of Madeleine's friends, she called out, "I thought that was you on the ground. You looked like a swami!"

"Congratulations, Mitchell!" Alton said, heartily shaking Mitchell's hand. "Big day today. One of the milestones. A new generation takes the reins."

They invited Mitchell to sit down and asked him if he wanted anything to eat. Madeleine went back to the counter to get more coffee, glad to have Mitchell keeping her parents occupied. As she watched him, in his old man's clothes, engaging Alton and Phyllida in conversation, Madeleine thought to herself, as she'd thought many times before, that Mitchell was the kind of smart, sane, parent-pleasing boy she should fall in love with and marry. That she would never fall in love with Mitchelland marry him, precisely because of this eligibility, was yet another indication, in a morning teeming with them, of just how screwed up she was in matters of the heart.

When she returned to the table, no one acknowledged her.

"So, Mitchell," Phyllida was asking, "what are your plans after graduation?"

"My father's been asking me the same question," Mitchell answered. "For some reason he thinks Religious Studies isn't a marketable degree."

Madeleine smiled for the first time all day. "See? Mitchell doesn't have a job lined up, either."

"Well, I sort of do," Mitchell said.

"You do not," Madeleine challenged him.

"I'm serious. I do." He explained that he and his roommate, Larry Pleshette, had come up with a plan to fight the recession. As liberal-arts degree holders matriculating into the job market at a time when unemployment was at 9.5 percent, they had decided, after much consideration, to leave the country and stay away as long as possible. At the end of the summer, after they'd saved up enough money, they were going to backpack through Europe. After they'd seen everything in Europe there was to see, they were going to fly to India and stay there as long as their money held out. The whole trip would take eight or nine months, maybe as long as a year.

"You're going to India?" Madeleine said. "That's not a job."

"We're going to be research assistants," Mitchell said. "For Prof. Hughes."

"Prof. Hughes in the theater department?"

"I saw a program about India recently," Phyllida said. "It was terribly depressing. The poverty!"

"That's a plus for me, Mrs. Hanna," Mitchell said. "I thrive in squalor."

Phyllida, who couldn't resist this sort of mischief, gave up her solemnity, rippling with amusement. "Then you're going to the right place!"

"Maybe I'll take a trip, too," Madeleine said in a threatening tone.

No one reacted. Instead Alton asked Mitchell, "What sort of immunizations do you need for India?"

"Cholera and typhus. Gamma globulin's optional."

Phyllida shook her head. "Your mother must be worried sick."

"When I was in the service," Alton said, "they shot us up with a million things. Didn't even tell us what the shots were for."

"I think I'll move to Paris," Madeleine said in a louder voice. "Instead of getting a job."

"Mitchell," Phyllida continued, "with your interest in religious studies, I'd think India would be a perfect fit. They've got everything. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Zoroastrians, Jains, Buddhists. It's like Baskin and Robbins! I've always been fascinated by religion. Unlike my doubting-Thomas husband."

Alton winked. "I doubt that doubting Thomas existed."

"Do you know Paul Moore, Bishop Moore, at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine?" Phyllida said, keeping Mitchell's attention. "He's a great friend. You might find it interesting to meet him. We'd be happy to introduce you. When we're in the city, I always go to services at the cathedral. Have you ever been there? Oh. Well. How can I describe it? It's simply--well, simply divine!"

Phyllida held a hand to her throat with the pleasure of this bon mot, while Mitchell obligingly, even convincingly, laughed.

"Speaking of religious dignitaries," Alton cut in, "did I ever tell you about the time we met the Dalai Lama? It was at this fund-raiser at the Waldorf. We were in the receiving line. Must have been three hundred people at least. Anyway, when we finally got up to the Dalai Lama, I asked him, 'Are you any relation to Dolly Parton?'"

"I was mortified!" Phyllida cried. "Absolutely mortified."

"Daddy," Madeleine said, "you're going to be late."

"What?"

"You should get going if you want to get a good spot."

Alton looked at his watch. "We've still got an hour."

"It gets really crowded," Madeleine emphasized. "You should go now."

Alton and Phyllida looked at Mitchell, as if they trusted him to advise them. Under the table, Madeleine kicked him, and he alertly responded, "It does get pretty crowded."

"Where's the best place to stand?" Alton asked, again addressing Mitchell.

"By the Van Wickle Gates. At the top of College Street. That's where we'll come through."

Alton stood up from the table. After shaking Mitchell's hand, hebent to kiss Madeleine on the cheek. "We'll see you later. Miss Baccalaureate, 1982."

"Congratulations, Mitchell," Phyllida said. "So nice to see you. And remember, when you're on your Grand Tour, be sure to send your mother loads of letters. Otherwise, she'll be frantic."

To Madeleine, she said, "You might change that dress before the march. It has a visible stain."

With that, Alton and Phyllida, in their glaring parental actuality, all seersucker and handbag, cuff links and pearls, crossed the beige-and-brick space of Carr House and went out the door.

As though to signal their departure, a new song came on: Joe Jackson's high-pitched voice swooping above a synthesized drumbeat. The guy behind the counter cranked up the volume.

Madeleine laid her head on the table, her hair covering her face.

"I'm never drinking again," she said.

"Famous last words."

"You have no idea what's been going on with me."

"How could I? You haven't been speaking to me."

Without lifting her cheek from the table, Madeleine said in a pitiful voice, "I'm homeless. I'm graduating from college and I'm a homeless person."

"Yeah, sure."

"I am!" Madeleine insisted. "First I was supposed to move to New York with Abby and Olivia. Then it looked like I was moving to the Cape, though, so I told them to get another roommate. And now I'm not moving to the Cape and I have nowhere to go. My mother wants me to move back home but I'd rather kill myself."

"I'm moving back home for the summer," Mitchell said. "To Detroit. At least you're near New York."

"I haven't heard back from grad school yet and it's June," Madeleine continued. "I was supposed to find out over a month ago! I could call the admissions department, but I don't because I'm scared to find out that I've been rejected. As long as I don't know, I still have hope."

There was a moment before Mitchell spoke again. "You can come to India with me," he said.

Madeleine opened one eye to see, through a whorl in her hair, that Mitchell wasn't entirely joking.

"It's not even about grad school," she said. Taking a deep breath, she confessed, "Leonard and I broke up."

It felt deeply pleasurable to say this, to name her sadness, and so Madeleine was surprised by the coldness of Mitchell's reply.

"Why are you telling me this?" he said.

She lifted her head, brushing her hair out of her face. "I don't know. You wanted to know what was the matter."

"I didn't, actually. I didn't even ask."

"I thought you might care," Madeleine said. "Since you're my friend."

"Right," Mitchell said, his voice suddenly sarcastic. "Our wonderful friendship! Our 'friendship' isn't a real friendship because it only works on your terms. You set the rules, Madeleine. If you decide you don't want to talk to me for three months, we don't talk. Then you decide you do want to talk to me because you need me to entertain your parents--and now we're talking again. We're friends when you want to be friends, and we're never more than friends because you don't want to be. And I have to go along with that."

"I'm sorry," Madeleine said, feeling put-upon and blindsided. "I just don't like you that way."

"Exactly!" Mitchell cried. "You're not attracted to me physically. O.K., fine. But who says I was ever attracted to you mentally?"

Madeleine reacted as if she'd been slapped. She was outraged, hurt, and defiant all at once.

"You're such a"--she tried to think of the worst thing to say--"you're such a jerk!" She was hoping to remain imperious, but her chest was stinging, and, to her dismay, she burst into tears.

Mitchell reached out to touch her arm, but Madeleine shook him off. Getting to her feet, trying not to look like someone angrily weeping, she went out the door and down the steps onto Waterman Street. Confronted by the festive churchyard, she turned downhill toward the river. She wanted to get away from campus. Her headache had returned, her temples were throbbing, and as she looked up at the storm clouds massing over downtown like more bad things to come, she asked herself why everyone was being so mean to her.

Madeleine's love troubles had begun at a time when the French theory she was reading deconstructed the very notion of love. Semiotics 211was an upper-level seminar taught by a former English department renegade. Michael Zipperstein had come to Brown thirty-two years earlier as a New Critic. He'd inculcated the habits of close reading and biography-free interpretation into three generations of students before taking a Road to Damascus sabbatical, in Paris, in 1975, where he'd met Roland Barthes at a dinner party and been converted, over cassoulet, to the new faith. Now Zipperstein taught two courses in the newly created Program in Semiotics Studies: Introduction to Semiotic Theory in the fall and, in the spring, Semiotics 211. Hygienically bald, with a seaman's mustache-less white beard, Zipperstein favored French fisherman's sweaters and wide-wale corduroys. He buried people with his reading lists: in addition to all the semiotic big hitters--Derrida, Eco, Barthes--the students in Semiotics 211 had to contend with a magpie nest of reserve reading that included everything from Balzac's Sarrasine to issues of Semiotext(e) to photocopied selections from E. M. Cioran, Robert Walser, Claude Levi-Strauss, Peter Handke, and Carl Van Vechten. To get into the seminar, you had to submit to a one-on-one interview with Zipperstein during which he asked bland personal questions, such as what your favorite food or dog breed was, and made enigmatic Warholian remarks in response. This esoteric probing, along with Zipperstein's guru's dome and beard, gave his students a sense that they'd been spiritually vetted and were now--for two hours on Thursday afternoons, at least--part of a campus lit-crit elite.

Which was exactly what Madeleine wanted. She'd become an English major for the purest and dullest of reasons: because she loved to read. The university's "British and American Literature Course Catalog" was, for Madeleine, what its Bergdorf equivalent was for her roommates. A course listing like "English 274: Lyly's Euphues" excited Madeleine the way a pair of Fiorucci cowboy boots did Abby. "English 450A: Hawthorne and James" filled Madeleine with an expectation of sinful hours in bed not unlike what Olivia got from wearing a Lycra skirt and leather blazer to Danceteria. Even as a girl in their house in Prettybrook, Madeleine wandered into the library, with its shelves of books rising higher than she could reach--newly purchased volumes such as Love Story or Myra Breckinridge that exuded a faintly forbidden air, as well as venerable leather-bound editions of Fielding, Thackeray, and Dickens--and the magisterial presence of all those potentially readable wordsstopped her in her tracks. She could scan book spines for as long as an hour. Her cataloging of the family's holdings rivaled the Dewey decimal system in its comprehensiveness. Madeleine knew right where everything was. The shelves near the fireplace held Alton's favorites, biographies of American presidents and British prime ministers, memoirs by warmongering secretaries of state, novels about sailing or espionage by William F. Buckley, Jr. Phyllida's books filled the left side of the bookcases leading up to the parlor, NYRB-reviewed novels and essay collections, as well as coffee-table volumes about English gardens or chinoiserie. Even now, at bed-and-breakfasts or seaside hotels, a shelf full of forlorn books always cried out to Madeleine. She ran her fingers over their salt-spotted covers. She peeled apart pages made tacky by ocean air. She had no sympathy for paperback thrillers and detective stories. It was the abandoned hardback, the jacketless 1931 Dial Press edition ringed with many a coffee cup, that pierced Madeleine's heart. Her friends might be calling her name on the beach, the clambake already under way, but Madeleine would sit down on the bed and read for a little while to make the sad old book feel better. She had read Longfellow's "Hiawatha" that way. She'd read James Fenimore Cooper. She'd read H. M. Pulham, Esquire by John P. Marquand.

And yet sometimes she worried about what those musty old books were doing to her. Some people majored in English to prepare for law school. Others became journalists. The smartest guy in the honors program, Adam Vogel, a child of academics, was planning on getting a Ph.D. and becoming an academic himself. That left a large contingent of people majoring in English by default. Because they weren't left-brained enough for science, because history was too dry, philosophy too difficult, geology too petroleum-oriented, and math too mathematical--because they weren't musical, artistic, financially motivated, or really all that smart, these people were pursuing university degrees doing something no different from what they'd done in first grade: reading stories. English was what people who didn't know what to major in majored in.

Her junior year, Madeleine had taken an honors seminar called The Marriage Plot: Selected Novels of Austen, Eliot, and James. The class was taught by K. McCall Saunders. Saunders was a seventy-nine-year-old New Englander. He had a long, horsey face and a moist laugh that exposed his gaudy dental work. His pedagogical method consisted of hisreading aloud lectures he'd written twenty or thirty years earlier. Madeleine stayed in the class because she felt sorry for Professor Saunders and because the reading list was so good. In Saunders's opinion, the novel had reached its apogee with the marriage plot and had never recovered from its disappearance. In the days when success in life had depended on marriage, and marriage had depended on money, novelists had had a subject to write about. The great epics sang of war, the novel of marriage. Sexual equality, good for women, had been bad for the novel. And divorce had undone it completely. What would it matter whom Emma married if she could file for separation later? How would Isabel Archer's marriage to Gilbert Osmond have been affected by the existence of a prenup? As far as Saunders was concerned, marriage didn't mean much anymore, and neither did the novel. Where could you find the marriage plot nowadays? You couldn't. You had to read historical fiction. You had to read non-Western novels involving traditional societies. Afghani novels, Indian novels. You had to go, literarily speaking, back in time.

Madeleine's final paper for the seminar was titled "The Interrogative Mood: Marriage Proposals and the (Strictly Limited) Sphere of the Feminine." It had impressed Saunders so much that he'd asked Madeleine to come see him. In his office, which had a grandparental smell, he expressed his opinion that Madeleine might expand her paper into a senior honors thesis, along with his willingness to serve as her advisor. Madeleine smiled politely. Professor Saunders specialized in the periods she was interested in, the Regency leading into the Victorian era. He was sweet, and learned, and it was clear from his unsubscribed office hours that no one else wanted him as an advisor, and so Madeleine had said yes, she would love to work with him on her senior thesis.

She used a line from Trollope's Barchester Towers as an epigraph: "There is no happiness in love, except at the end of an English novel." Her plan was to begin with Jane Austen. After a brief examination of Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, and Sense and Sensibility, all comedies, essentially, that ended with weddings, Madeleine was going to move on to the Victorian novel, where things got more complicated and considerably darker. Middlemarch and The Portrait of a Lady didn't end with weddings. They began with the traditional moves of the marriage plot--the suitors, the proposals, the misunderstandings--but after the weddingceremony they kept on going. These novels followed their spirited, intelligent heroines, Dorothea Brooke and Isabel Archer, into their disappointing married lives, and it was here that the marriage plot reached its greatest artistic expression.

By 1900 the marriage plot was no more. Madeleine planned to end with a brief discussion of its demise. In Sister Carrie, Dreiser had Carrie live adulterously with Drouet, marry Hurstwood in an invalid ceremony, and then run off to become an actress--and this was only in 1900! For a conclusion, Madeleine thought she might cite the wife-swapping in Updike. That was the last vestige of the marriage plot: the persistence in calling it "wife-swapping" instead of "husband-swapping." As if the woman were still a piece of property to be passed around.

Professor Saunders suggested that Madeleine look at historical sources. She'd obediently boned up on the rise of industrialism and the nuclear family, the formation of the middle class, and the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857. But it wasn't long before she'd become bored with the thesis. Doubts about the originality of her work nagged at her. She felt as if she was regurgitating the arguments Saunders had made in his marriage plot seminar. Her meetings with the old professor were dispiriting, consisting of Saunders shuffling the pages she'd given him, pointing out various red marks he'd made in the margins.

Then one Sunday morning, before winter break, Abby's boyfriend, Whitney, materialized at their kitchen table, reading something called Of Grammatology. When Madeleine asked what the book was about, she was given to understand by Whitney that the idea of a book being "about" something was exactly what this book was against, and that, if it was "about" anything, then it was about the need to stop thinking of books as being about things. Madeleine said she was going to make coffee. Whitney asked if she would make him some, too.

College wasn't like the real world. In the real world people dropped names based on their renown. In college, people dropped names based on their obscurity. Thus, in the weeks after this exchange with Whitney, Madeleine began hearing people saying "Derrida." She heard them saying "Lyotard" and "Foucault" and "Deleuze" and "Baudrillard." That most of these people were those she instinctually disapproved of--upper-middle-class kids who wore Doc Martens and anarchist symbols--made Madeleine dubious about the value of their enthusiasm. But soon shenoticed David Koppel, a smart and talented poet, also reading Derrida. And Pookie Ames, who read slush for The Paris Review and whom Madeleine liked, was taking a course with Professor Zipperstein. Madeleine had always been partial to grandiose professors, people like Sears Jayne who hammed it up in the classroom, reciting Hart Crane or Anne Sexton in a gag voice. Whitney acted as though Professor Jayne was a joke. Madeleine didn't agree. But after three solid years of taking literature courses, Madeleine had nothing like a firm critical methodology to apply to what she read. Instead she had a fuzzy, unsystematic way of talking about books. It embarrassed her to hear the things people said in class. And the things she said. I felt that. It was interesting the way Proust. I liked the way Faulkner.

And when Olivia, who was tall and slim, with a long, aristocratic nose like a saluki, came in one day carrying Of Grammatology, Madeleine knew that what had been marginal was now mainstream.

"What's that book like?"

"You haven't read it?"

"Would I be asking if I had?"

Olivia sniffed. "Aren't we a little bitchy today?"

"Sorry."

"Just kidding. It's great. Derrida is my absolute god!"

Almost overnight it became laughable to read writers like Cheever or Updike, who wrote about the suburbia Madeleine and most of her friends had grown up in, in favor of reading the Marquis de Sade, who wrote about anally deflowering virgins in eighteenth-century France. The reason de Sade was preferable was that his shocking sex scenes weren't about sex but politics. They were therefore anti-imperialist, anti-bourgeois, anti-patriarchal, and anti-everything a smart young feminist should be against. Right up through her third year at college, Madeleine kept wholesomely taking courses like Victorian Fantasy: From Phantastes to The Water-Babies, but by senior year she could no longer ignore the contrast between the hard-up, blinky people in her Beowulf seminar and the hipsters down the hall reading Maurice Blanchot. Going to college in the moneymaking eighties lacked a certain radicalism. Semiotics was the first thing that smacked of revolution. It drew a line; it created an elect; it was sophisticated and Continental; it dealt with provocative subjects, with torture, sadism, hermaphroditism--with sex and power.Madeleine had always been popular at school. Years of being popular had left her with the reflexive ability to separate the cool from the uncool, even within subgroups, like the English department, where the concept of cool didn't appear to obtain.

If Restoration drama was getting you down, if scanning Wordsworth was making you feel dowdy and ink-stained, there was another option. You could flee K. McCall Saunders and the old New Criticism. You could defect to the new imperium of Derrida and Eco. You could sign up for Semiotics 211 and find out what everyone else was talking about.

Semiotics 211 was limited to ten students. Of the ten, eight had taken Introduction to Semiotic Theory. This was visually apparent at the first class meeting. Lounging around the seminar table, when Madeleine came into the room from the wintry weather outside, were eight people in black T-shirts and ripped black jeans. A few had razored off the necks or sleeves of their T-shirts. There was something creepy about one guy's face--it was like a baby's face that had grown whiskers--and it took Madeleine a full minute to realize that he'd shaved off his eyebrows. Everyone in the room was so spectral-looking that Madeleine's natural healthiness seemed suspect, like a vote for Reagan. She was relieved, therefore, when a big guy in a down jacket and snowmobile boots showed up and took the empty seat next to her. He had a cup of take-out coffee.

Zipperstein asked the students to introduce themselves and explain why they were taking the seminar.

The boy without eyebrows spoke up first. "Um, let's see. I'm finding it hard to introduce myself, actually, because the whole idea of social introductions is so problematized. Like, if I tell you that my name is Thurston Meems and that I grew up in Stamford, Connecticut, will you know who I am? O.K. My name's Thurston and I'm from Stamford, Connecticut. I'm taking this course because I read Of Grammatology last summer and it blew my mind." When it was the turn of the boy next to Madeleine, he said in a quiet voice that he was a double major (biology and philosophy) and had never taken a semiotics course before, that his parents had named him Leonard, that it had always seemed pretty handy to have a name, especially when you were being called to dinner, and that if anyone wanted to call him Leonard he would answer to it.

Leonard didn't make another comment. During the rest of the class,he leaned back in his chair, stretching out his long legs. After he finished his coffee, he dug into his right snowmobile boot and, to Madeleine's surprise, pulled out a tin of chewing tobacco. With two stained fingers, he placed a wad of tobacco in his cheek. For the next two hours, every minute or so, he spat, discreetly but audibly, into the cup.

Every week Zipperstein assigned one daunting book of theory and one literary selection. The pairings were eccentric if not downright arbitrary. (What did Saussure's Writings in General Linguistics, for instance, have to do with Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49?) As for Zipperstein himself, he didn't run the class so much as observe it from behind the one-way mirror of his opaque personality. He hardly said a word. He asked questions now and then to stimulate discussion, and often went to the window to gaze in the direction of Narragansett Bay, as if thinking about his wooden sloop in dry dock.

Three weeks into the course, on a February day of flurries and gray skies, they read Zipperstein's own book, The Making of Signs, along with Peter Handke's A Sorrow Beyond Dreams.

It was always embarrassing when professors assigned their own books. Even Madeleine, who found all the reading hard going, could tell that Zipperstein's contribution to the field was reformulative and second-tier.

Everyone seemed a little hesitant when talking about The Making of Signs, so it was a relief when, after the break, they turned to the literary selection.

"So," Zipperstein asked, blinking behind his round wire-rims. "What did you make of the Handke?"

After a short silence, Thurston spoke up. "The Handke was totally dank and depressing," he said. "I loved it."

Thurston was a sly-looking boy with short, gelled hair. His eyebrow-lessness, along with his pale complexion, gave his face a superintelligent quality, like a floating, disembodied brain.

"Care to elaborate?" Zipperstein said.

"Well, Professor, here's a subject dear to my heart--offing yourself." The other students tittered as Thurston warmed to his topic. "It's purportedly autobiographical, this book. But I'd contend, with Barthes, that the act of writing is itself a fictionalization, even if you're treating actual events."

Bart. So that was how you pronounced it. Madeleine made a note, grateful to be spared humiliation.

Meanwhile Thurston was saying, "So Handke's mother commits suicide and Handke sits down to write about it. He wants to be as objective as possible, to be totally--remorseless!" Thurston stifled a smile. He aspired to be a person who would react to his own mother's suicide with high-literary remorselessness, and his soft, young face lit up with pleasure. "Suicide is a trope," he announced. "Especially in German literature. You've got The Sorrows of Young Werther. You've got Kleist. Hey, I just thought of something." He held up a finger. "The Sorrows of Young Werther." He held up another finger. "A Sorrow Beyond Dreams. My theory is that Handke felt the weight of all that tradition and this book was his attempt to break free."

"How do you mean 'free'?" Zipperstein said.

"From the whole Teutonic, Sturm-und-Drang, suicidal thing."

The flurries swirling outside the windows looked like either flakes of soap or flash of ash, like something either very clean or very dirty.

"The Sorrows of Young Werther is an apt reference," Zipperstein said. "But I think that's more the translator's doing than Handke's. In German the book's called Wunschloses Unglück."

Thurston smiled, either because he was pleased to be receiving Zipperstein's full attention or because he thought German sounded funny.

"It's a play on a German saying, wunschlos glücklich, which means being happier than you could ever wish for. Only here Handke makes a nice reversal. It's a serious and strangely wonderful title."

"So it means being unhappier than you could ever wish for," Madeleine said.

Zipperstein looked at her for the first time.

"In a sense. As I said, something is lost in translation. What was your take?"

"On the book?" Madeleine asked, and immediately realized how stupid this sounded. She fell silent, the blood beating in her ears.

People blushed in nineteenth-century English novels but never in contemporary Austrian ones.

Before the silence became uncomfortable, Leonard came to her rescue. "I have a comment," he said. "If I was going to write about my mother's suicide, I don't think I'd be too concerned about being experimental." Heleaned forward, putting his elbows on the table. "I mean, wasn't anybody put off by Handke's so-called remorselessness? Didn't this book strike anyone as a tad cold?"

"Better cold than sentimental," Thurston said.

"Do you think? Why?"

"Because we've read the sentimental, filial account of a cherished dead parent before. We've read it a million times. It doesn't have any power anymore."

"I'm doing a little thought experiment here," Leonard said. "Say my mother killed herself. And say I wrote a book about it. Why would I want to do something like that?" He closed his eyes and leaned his head back. "First, I'd do it to cope with my grief. Second, maybe to paint a portrait of my mother. To keep her alive in my memory."

"And you think your reaction is universal," Thurston said. "That because you'd respond to the death of a parent a certain way, that obligates Handke to do the same."

"I'm saying that if your mother kills herself it's not a literary trope."

Madeleine's heart had quieted now. She was listening to the discussion with interest.

Thurston was nodding his head in a way that somehow didn't suggest agreement. "Yeah, O.K.," he said. "Handke's real mother killed herself. She died in a real world and Handke felt real grief or whatever. But that's not what this book's about. Books aren't about 'real life.' Books are about other books." He raised his mouth like a wind instrument and blew out bright notes. "My theory is that the problem Handke was trying to solve here, from a literary standpoint, was how do you write about something, even something real and painful--like suicide--when all of the writing that's been done on that subject has robbed you of any originality of expression?"

What Thurston was saying seemed to Madeleine both insightful and horribly wrong. It was maybe true, what he said, but it shouldn't have been.

"'Popular literature,'" Zipperstein quipped, proposing an essay title. "'Or, How to Beat a Dead Horse.'"

A spasm of mirth traveled through the class. Madeleine looked over to see that Leonard was staring at her. When the class ended, he gathered up his books and left.

She started seeing Leonard around after that. She saw him crossing the green one afternoon, hatless in winter drizzle. She saw him at Mutt & Geoff's, eating a messy Buddy Cianci sandwich. She saw him, one morning, waiting for a bus on South Main. Each time, Leonard was alone, looking forlorn and uncombed like a great big motherless boy. At the same time, he appeared somehow older than most guys at school.

It was Madeleine's last semester of senior year, a time when she was supposed to have some fun, and she wasn't having any. She'd never thought of herself as hard up. She preferred to think of her current boy-friendless state as salutary and head-clearing. But when she found herself wondering what it would be like to kiss a guy who chewed tobacco, she began to worry that she was fooling herself.

Looking back, Madeleine realized that her college love life had fallen short of expectations. Her freshman roommate, Jennifer Boomgaard, had rushed off to Health Services the first week of school to be fitted for a diaphragm. Unaccustomed to sharing a room with anybody, much less a stranger, Madeleine felt that Jenny was a little too quick with her intimacies. She didn't want to be shown Jennifer's diaphragm, which reminded her of an uncooked ravioli, and she certainly didn't want to feel the spermicidal jelly that Jenny offered to squirt into her palm. Madeleine was shocked when Jennifer started going to parties with the diaphragm already in place, when she wore it to the Harvard-Brown game, and when she left it one morning on top of their miniature fridge. That winter, when the Rev. Desmond Tutu came to campus for an anti-apartheid rally, Madeleine asked Jennifer on their way to see the great cleric, "Did you put your diaphragm in?" They lived the next four months in an eighteen-by-fifteen room without speaking to each other.

Though Madeleine hadn't arrived at college sexually inexperienced, her freshman learning curve resembled a flat line. Aside from one make-out session with a Uruguayan named Carlos, a sandal-wearing engineering student who in low light looked like Che Guevara, the only boy she'd fooled around with was a high school senior visiting campus for Early Action weekend. She found Tim standing in line at the Ratty, pushing his cafeteria tray along the metal track, and visibly quivering. His blue blazer was too big for him. He'd spent the entire day wandering around campus with no one speaking to him. Now he was starving and wasn't sure if he was allowed to eat in the cafeteria or not. Tim seemedto be the only person at Brown more lost than Madeleine. She helped him negotiate the Ratty and, afterward, took him on a tour of the university. Finally, around ten-thirty that night, they ended up back in Madeleine's dorm room. Tim had the long-lashed eyes and pretty features of an expensive Bavarian doll, a little prince or yodeling shepherd boy. His blue blazer was on the floor and Madeleine's shirt unbuttoned when Jennifer Boomgaard came through the door. "Oh," she said, "sorry," and proceeded to stand there, smiling at the floor as if already relishing how this juicy bit of gossip would play along the hall. When she finally did leave, Madeleine sat up and readjusted her clothes, and Tim picked up his blazer and went back to high school.

At Christmas, when Madeleine went home for vacation, she thought the scale in her parents' bathroom was broken. She got off to recalibrate the dial and got back on, whereupon the scale again registered the same weight. Stepping in front of the mirror, Madeleine encountered a worried chipmunk staring back. "Am I not getting asked out because I'm fat," the chipmunk said, "or am I fat because I'm not getting asked out?"

"I never got the freshman fifteen," her sister gloated when Madeleine came down to breakfast. "But I didn't pig out like all my friends did." Accustomed to Alwyn's teasing, Madeleine paid no attention, quietly slicing and eating the first of the fifty-seven grapefruits she subsisted on until New Year's.

Dieting fooled you into thinking you could control your life. By January, Madeleine was down five pounds, and by the time squash season ended she was back in great shape, and still she didn't meet anyone she liked. The boys at college seemed either incredibly immature or prematurely middle-aged, bearded like therapists, warming brandy snifters over candles while listening to Coltrane's A Love Supreme. It wasn't until her junior year that Madeleine had a serious boyfriend. Billy Bainbridge was the son of Dorothy Bainbridge, whose uncle owned a third of the newspapers in the United States. Billy had flushed cheeks, blond curls, and a scar on his right temple that made him even more adorable than he already was. He was soft-spoken and nice-smelling, like Ivory soap. Naked, his body was nearly hairless.

Billy didn't like to talk about his family. Madeleine took this as a sign of good breeding. Billy was a legacy at Brown and sometimes worried that he wouldn't have gotten in on his own. Sex with Billy was cozy, itwas snuggly, it was perfectly fine. He wanted to be a filmmaker. The one film he made for Advanced Filmmaking, however, was a violent, unbroken twelve minutes of Billy throwing fecal-looking brownie mix at the camera. Madeleine began to wonder if there was a reason he never talked about his family.

One thing he did talk about, however, with increasing intensity, was circumcision. Billy had read an article in an alternative health magazine that argued against the practice, and it made a big impression on him. "If you think about it, it's a pretty weird thing to do to a baby," he said. "Cut off part of its dick? What's so different about a tribe in, like, Papua New Guinea putting bones through their noses and cutting off a baby's foreskin? A bone through the nose is a lot less invasive." Madeleine listened, trying to look sympathetic, and hoped Billy would drop the subject. But as the weeks passed he kept returning to it. "The doctors just do it automatically in this country," he said. "They didn't ask my parents. It's not like I'm Jewish or anything." He derided justifications on the basis of health or hygiene. "Maybe that made sense three thousand years ago, out in the desert, when you couldn't take a shower. But now?"

One night, as they were lying in bed, naked, Madeleine noticed Billy examining his penis, stretching it.

"What are you doing?" she asked.

"I'm looking for the scar," he said somberly.

He interrogated his European friends, Henrik the Intact, Olivier the Foreskinned, asking, "But does it feel supersensitive?" Billy was convinced that he'd been deprived of sensation. Madeleine tried not to take this personally. Plus there were other problems with their relationship by then. Billy had a habit of staring deeply into Madeleine's eyes in a way that was somehow controlling. His roommate situation was odd. He lived off campus with an attractive, muscular girl named Kyle who was sleeping with at least three people, including Fatima Shirazi, a niece of the shah of Iran. On the wall of his living room Billy had painted the words Kill the Father. Killing the father was what, in Billy's opinion, college was all about.

"Who's your father?" he asked Madeleine. "Is it Virginia Woolf? Is it Sontag?"

"In my case," Madeleine said, "my father really is my father."

"Then you have to kill him."

"Who's your father?"

"Godard," he said.

Billy talked about renting a house in Guanajuato with Madeleine over the summer. He said she could write a novel while he made a film. His faith in her, in her writing (even though she hardly wrote any fiction), made Madeleine feel so good that she started going along with the idea. And then one day she came up onto Billy's front porch and was about to rap on his window when something told her to look in the window instead. In the storm-tossed bed, Billy lay curled, John Lennon-style, against the spread-eagled Kyle. Both were naked. A second later, in a puff of smoke, Fatima materialized, also naked, shaking baby powder over her gleaming Persian skin. She smiled at her bedmates, her teeth seed-like in purple, royal gums.

Maddy's next boyfriend wasn't strictly her fault. She would never have met Dabney Carlisle if she hadn't taken an acting class, and she would never have taken an acting class if it hadn't been for her mother. As a young woman, Phyllida had wanted to be an actress. Her parents had been opposed, however. "Acting wasn't what people in our family, especially the ladies, did," was the way Phyllida put it. Every so often, in reflective moods, she told her daughters the story of her one great disobedience. After graduating from college, Phyllida had "run away" to Hollywood. Without telling her parents, she'd flown out to Los Angeles, staying with a friend from Smith. She'd found a job as a secretary in an insurance company. She and the friend, a girl named Sally Peyton, moved into a bungalow in Santa Monica. In six months Phyllida had three auditions, one screen test, and "loads of invitations." She'd once seen Jackie Gleason carrying a chihuahua into a restaurant. She'd developed a lustrous suntan she described as "Egyptian." Whenever Phyllida spoke about this period in her life, it seemed as if she was talking about another person. As for Alton, he became quiet, fully aware that Phyllida's loss had been his gain. It was on the train back to New York, the next Christmas, that she'd met the straight-backed lieutenant colonel, recently returned from Berlin. Phyllida never went back to L.A. She got married instead. "And had you two," she told her daughters.

Phyllida's inability to realize her dreams had given Madeleine her own. Her mother's life was the great counterexample. It represented the injustice Madeleine's life would rectify. To come of age simultaneously with a great social movement, to grow up in the age of Betty Friedan andERA marches and Bella Abzug's indomitable hats, to define your identity when it was being redefined, this was a freedom as great as any of the American freedoms Madeleine had read about in school. She could remember the night, in 1973, when her family gathered before the television in the den to watch the tennis match between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs. How she, Alwyn, and Phyllida had rooted for Billie Jean, while Alton had pulled for Bobby Riggs. How, as King ran Riggs back and forth across the court, outserving him, hitting winners he was too slow to return, Alton began to grumble. "It's not a fair fight! Riggs is too old. If they want a real test, she should play Smith or Newcombe." But it didn't matter what Alton said. It didn't matter that Bobby Riggs was fifty-five and King twenty-nine, or that Riggs hadn't been an especially great player even in his prime. What mattered was that this tennis match was on national television, during prime time, billed for weeks as "The Battle of the Sexes," and that the woman was winning. If any single moment defined Madeleine's generation of girls, dramatized their aspirations, put into clear focus what they expected from themselves and from life, it was those two hours and fifteen minutes when the country watched a man in white shorts get thrashed by a woman, pummeled repeatedly until all he could do, after match point, was to jump feebly over the net. And even that was telling: you were supposed to jump the net when you won, not lost. So how male was that, to act like a winner when you'd just been creamed?

At the first meeting of Acting Workshop, Professor Churchill, a bald bullfrog of a man, asked the students to say something about themselves. Half the people in the class were theater majors, serious about acting or directing. Madeleine mumbled something about loving Shakespeare and Eugene O'Neill.

Dabney Carlisle stood up and said, "I've done a little modeling work, down in New York. My agent suggested I should take some acting lessons. So here I am."

The modeling he'd done consisted of a single magazine ad, showing a group of Leni Riefenstahl-ish athletes in boxer briefs, standing in a receding line on a beach whose black volcanic sand steamed around their marble feet. Madeleine didn't see the photograph until she and Dabney were already going out, when Dabney gingerly took it out of the bartending manual where he kept it safely pressed. She was inclined tomake fun of it but something reverential in Dabney's expression stopped her. And so she asked where the beach had been (Montauk) and why it was so black (it wasn't) and how much he'd gotten paid ("four figures") and what the other guys were like ("total a-holes") and if he was wearing the underpants right now. It was sometimes difficult, with boys, to take an interest in the things that interested them. But with Dabney she wished it had been curling, she longed for it to be the model UN, anything but male modeling. This, anyway, was the authentic emotion she now identified herself as having felt. At the time--Dabney cautioned her against touching the ad before he got it laminated--Madeleine had rehearsed in her mind the standard arguments: that though objectification was de facto bad, the emergence of the idealized male form in the mass media scored a point for equality; that if men started getting objectified and started worrying about their looks and their bodies, they might begin to understand the burden women had been living with since forever, and might therefore be sensitized to these issues of the body. She even went so far as to admire Dabney for his courage in allowing himself to be photographed in snug little gray underpants.

Looking the way Madeleine and Dabney did, it was inevitable that they would be cast as romantic leads in the scenes the workshop performed. Madeleine was Rosalind to Dabney's wooden Orlando, Maggie to his brick-like Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. To rehearse the first time, they met at Dabney's fraternity house. Merely stepping through the front door reinforced Madeleine's aversion to places like Sigma Chi. It was around ten on a Sunday morning. The vestiges of the previous evening's "Hawaiian Night" were still there to see--the lei hanging from the antlers of the moose head on the wall, the plastic "grass" skirt trampled on the beer-sodden floor, a skirt that, should Madeleine succumb to the outrageous good looks of Dabney Carlisle, she might, at a minimum, have to watch some drunken slut hula in to the baying of the brothers, or, at a maximum (for mai tais made you do crazy things), might even don herself, up in Dabney's room, for his pleasure alone. On the low-slung couch two Sigma Chi members were watching TV. At Madeleine's appearance, they stirred, rising out of the gloom like openmouthed carp. She hurried to the back stairs, thinking the things she always thought when it came to frats and frat guys: that their appeal stemmed from a primitive need for protection (one thought of Neanderthal clansbanding together against other Neanderthal clans); that the hazing the pledges underwent (being stripped and blindfolded and left in the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel with bus fare taped to their genitals) enacted the very fears of male rape and emasculation that membership in the fraternity promised protection against; that any guy who longed to join a frat suffered from insecurities that poisoned his relationships with women; that there was something seriously wrong with homophobic guys who centered their lives around a homoerotic bond; that the stately mansions maintained by generations of dues-paying fraternity members were in reality sites for date rape and problem drinking; that frats always smelled bad; that you didn't ever want to shower in one; that only freshman girls were stupid enough to go to frat parties; that Kelly Traub had slept with a Sigma Delt guy who kept saying, "Now you see it, now you don't, now you see it, now you don't"; that such a thing wasn't going to happen to her, to Madeleine, ever.

What she hadn't expected when it came to a fraternity was a sunny-haired silent type like Dabney, learning his lines in a folding chair, in parachute pants, shoeless. Looking back on their relationship, Madeleine figured she'd had no choice. Dabney and she had been selected for each other in a Royal Wedding kind of way. She was Prince Charles to his Princess Di. She knew he couldn't act. Dabney had the artistic soul of a third-string tight end. In life Dabney moved and said little. Onstage he moved not at all but had to say a lot. His best dramatic moments came when the strain on his face from remembering his lines resembled the emotion he was trying to simulate.

Acting opposite Dabney made Madeleine more stiff and nervous than she already was. She wanted to do scenes with the talented kids in the workshop. She suggested interesting bits from The Vietnamization of New Jersey and Mamet's Sexual Perversity in Chicago, but got no takers. Nobody wanted to lower his or her average by acting with her.

Dabney didn't let it bother him. "Bunch of little shits in that class," he said. "They'll never get any print work, much less movies."

He was more laconic than she liked her boyfriends to be. He had the wit of a store mannequin. But Dabney's physical perfection pushed these realities out of her mind. She'd never been in a relationship where she wasn't the more attractive partner. It was slightly intimidating. But she could handle it. At three a.m., while Dabney lay sleeping beside her,Madeleine found she was up to the task of inventorying each abdominal cord, every hard lump of muscle. She enjoyed applying calipers to Dabney's waist to measure his body fat. Underwear modeling was all about the abs, Dabney said, and the abs were all about sit-ups and diet. The pleasure Madeleine got from looking at Dabney was reminiscent of the pleasure she'd gotten as a girl from looking at sleek hunting dogs. Underneath this pleasure, like the coals that fed it, was a fierce need to enfold Dabney and siphon off his strength and beauty. It was all very primitive and evolutionary and felt fantastic. The problem was that she hadn't been able to allow herself to enjoy Dabney or even to exploit him a little, but had had to go and be a total girl about it and convince herself that she was in love with him. Madeleine required emotion, apparently. She disapproved of the idea of meaningless, extremely satisfying sex.

And so she began to tell herself that Dabney's acting was "restrained" or "economical." She appreciated that Dabney was "secure about himself" and "didn't need to prove anything" and wasn't a "showoff." Instead of worrying that he was dull, Madeleine decided he was gentle. Instead of thinking he was poorly read, she called him intuitive. She exaggerated Dabney's mental abilities in order not to feel shallow for wanting his body. To this end she helped Dabney write--O.K., she wrote--English and anthro papers for him and, when he got A's, felt confirmed of his intelligence. She sent him off to modeling auditions in New York with good-luck kisses and listened to him complain bitterly about the "faggots" who hadn't hired his services. It turned out that Dabney wasn't so beautiful. Among the truly beautiful he was only so-so. He couldn't even smile right.

At the end of the semester, the acting students met separately with the professor for a critical review. Churchill welcomed Madeleine with a wolfish yellow grin, then sat back jowly and deliberate in his chair.

"I've enjoyed having you in the class, Madeleine," he said. "But you can't act."

"Don't hold back," Madeleine said, chastened but laughing. "Give it to me straight."

"You have a good feel for language, for Shakespeare especially. But your voice is reedy and you look worried onstage. Your forehead has a perpetual crease. A vocal coach could go a long way toward helping yourinstrument. But I worry about your worrying. You've got it right now. The crease."

"It's called thinking."

"Which is fine. If you're playing Eleanor Roosevelt. Or Golda Meir. But those parts don't come around very often."