In a recent New Yorker article, “Europe’s Other Migration Crisis,” writer Alexis Okeowo asks whether “the war in Ukraine will mean anything for Europe’s other refugee crisis — for the refugees who are not white, possibly not Christian, but who are also in need?”

Jonathan Bastian talks with Okeowo about the disparity when it comes to Black and brown refugees who flee conflict zones in fear for their lives — and the thousands of lives left to languish in the wastelands of refugee camps. Okeowo, a staff writer at The New Yorker, has traveled extensively across Africa as well as Mexico, reporting on conflict, human rights, and culture. She is also author of “A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa.” Okeowo describes what it’s like living in a refugee camp, without hope of being resettled, explaining that “the refugee camp, which was destined to be a temporary thing, has become a permanent living place … children are born there, go to school there, and grow up there.”

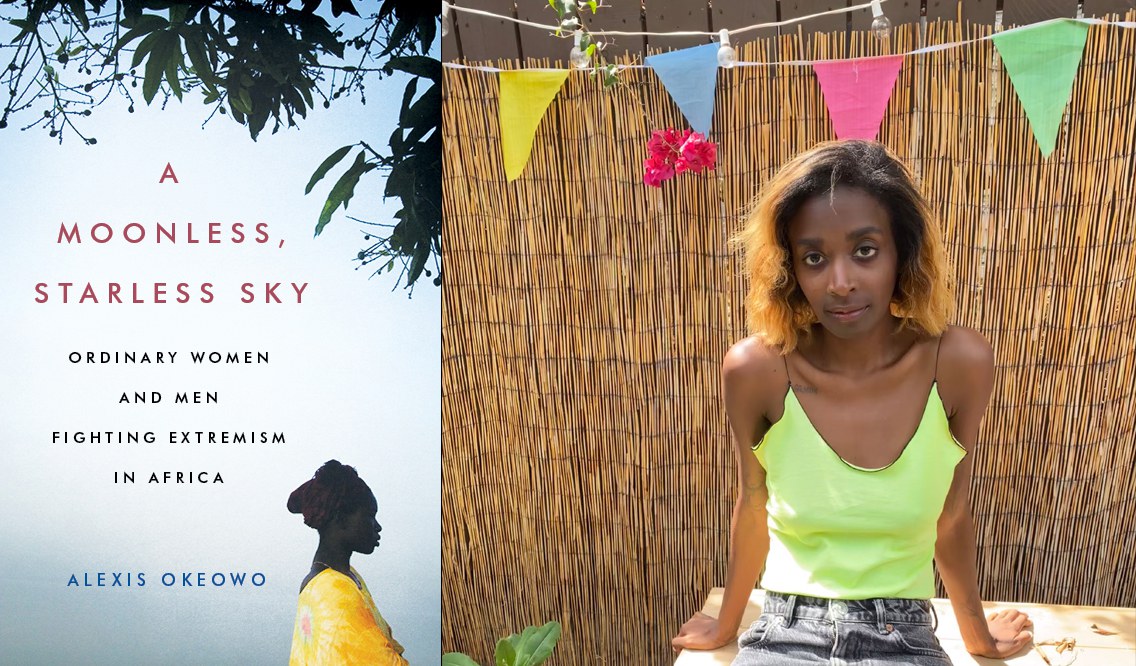

Book cover “A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa,” Alexis Okeowo. Photo courtesy of Alexis Okeowo

As we grapple with war fuelled tragedy and injustice, how do children manage in these conditions? Are they immune to fear? And what gives them hope and resilience? The conversation continues with Simon Lereng Wilmont, a Danish documentary filmmaker and director of two documentaries filmed in Eastern Ukraine: “The Distant Barking of Dogs” and “A House Made of Splinters.”

Wilmont follows the lives of children impacted by the ongoing conflict and documents what happens to them when society is torn apart by war. In “The Distant Barking of Dogs,” Wilmont describes the life of a young boy, Oleg, living near the frontline of the war with his grandmother. The documentary focuses on everyday survival of the war — how Oleg endures it with his grandmother, and the loss of innocence that comes with war. Kids, Wilmont says, have “natural resilience and a remarkable ability to adapt and to survive, and even to find the magic in life despite tragic circumstances.”

Photos still from "The Distant Barking of Dogs.” Photo courtesy of Simon Lereng Wilmont.