Crystal balls, horoscopes, and tea leaves — human nature has long been fascinated by the ability to peer into the future. But in the 1960s, a 42-year-old British psychiatrist, fascinated with precognition, decided to test a theory: Could premonitions be harnessed to help save lives?

On Oct. 21, 1966, a massive pile of coal ash descended on Aberfan, a Welsh mining village, smothering and killing 144 people, including 116 children in a school. In the aftermath of the disaster, Dr. John Barker arrived on the scene convinced that there had been early — and metaphysical — warning signs.

Bereaved families spoke of dreams on the eve of the disaster; a small boy drew figures digging in a hillside under the words “the end.” Kathleen Middleton, a music teacher l near London who experienced various premonitions throughout her life, awoke “choking and gasping and with the sense of the walls caving in.”

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.

Barker was intrigued, in part because Aberfan was so shocking, and in part because the way it occurred was so unusual, and wondered whether the event might offer a kind of singular place in the British consciousness. If some people were reliably able to foresee the future, could this information be communicated to authorities as a plausible early warning system to prevent disasters?

Barker took his hunches to the science editor of London’s Evening Standard newspaper and persuaded him to put out a national call for premonitions of the Aberfan disaster and other catastrophes — that is, to give a Premonitions Bureau a shot.

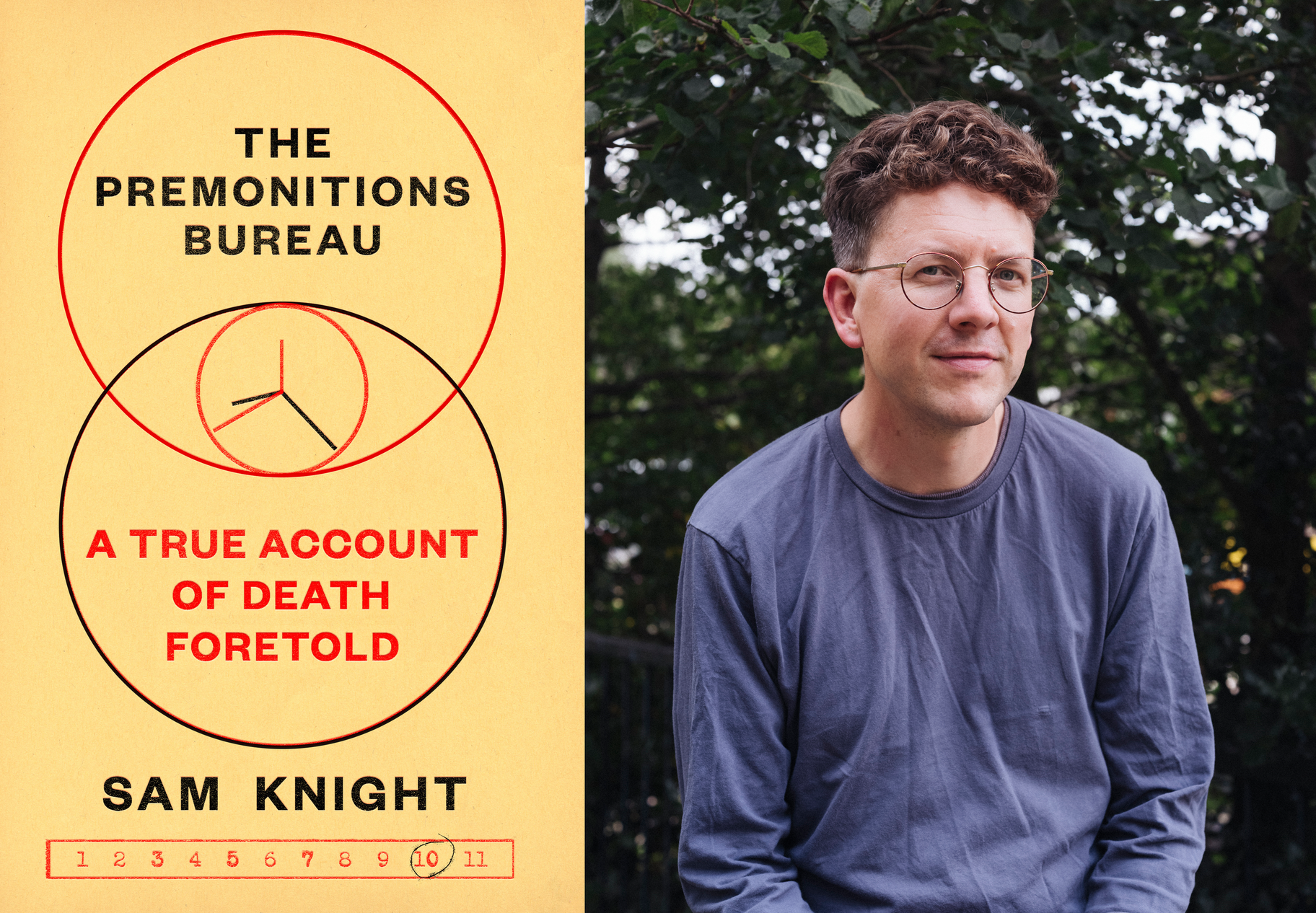

In his latest book, “The Premonitions Bureau: A True Account of Death Foretold,” author and New Yorker writer Sam Knight recounts the British psychiatrist and London science journalist who set up an office for people to call in with their visions.

“[Barker] was fascinating to me, because at the same time as being a modern, progressive doctor, he also had a part of his personality and mind in the occult, fascinated by ghosts. And for his whole career, these two things rubbed alongside each other,” says Sam Knight, pictured here, of Dr. John Barker. Photo by Olivia Arthur and Magnum Photos 2021. Book cover “The Premonitions Bureau: A True Account of Death Foretold.”

Jonathan Bastian talks with Knight about Barker and his collaborative idea to set up a small office to collect and verify premonitions.

“At the end of the first year, they had had about 45 premonitions, of which 18 of them were what he called ‘best buys,’” Knight says. “But ultimately, their success rate was less impressive, only around 3%.”

Knight also explores the human need to predict the future, and the power that those predictions have over the decisions we make. Could knowing the future risk a self-fulfilling prophecy? Is the brain already predisposed to predict the future?

“One of the ways that I think about premonitions is that they're part of the fabric of our thinking and how we make sense of our own experience and our own lives, generally,” Knight says. “We tend to play [down] the role of luck, hazard, and coincidence in our lives because we want there to be meaning and we need there to be meaning.”