The horrendous news of the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas this week has once again left a hole in our hearts. Nineteen elementary school children and two teachers were gunned down in their classrooms.

At times like this, many of us feel a collective loss; we relate to the mothers and fathers, despair at the slaughtered innocence, and mourn the needless loss of lives. How do we navigate those feelings of grief? What possible words could give solace to a parent who has lost a child?

Steve Leder, the Senior Rabbi of Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles and author of several book including “The Beauty of What Remains: How our Greatest Fear Becomes our Greatest Gift,” shares his thoughts and experiences on negotiating grief and loss. He says that when we are struck down with grief, it’s like an eclipse: “While in the midst of an eclipse, it is very easy to believe that the sun's light and energy has forever been extinguished, that darkness is more powerful than light, but eventually the eclipse recedes and our faith in the light and power of the sun is restored.”

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.

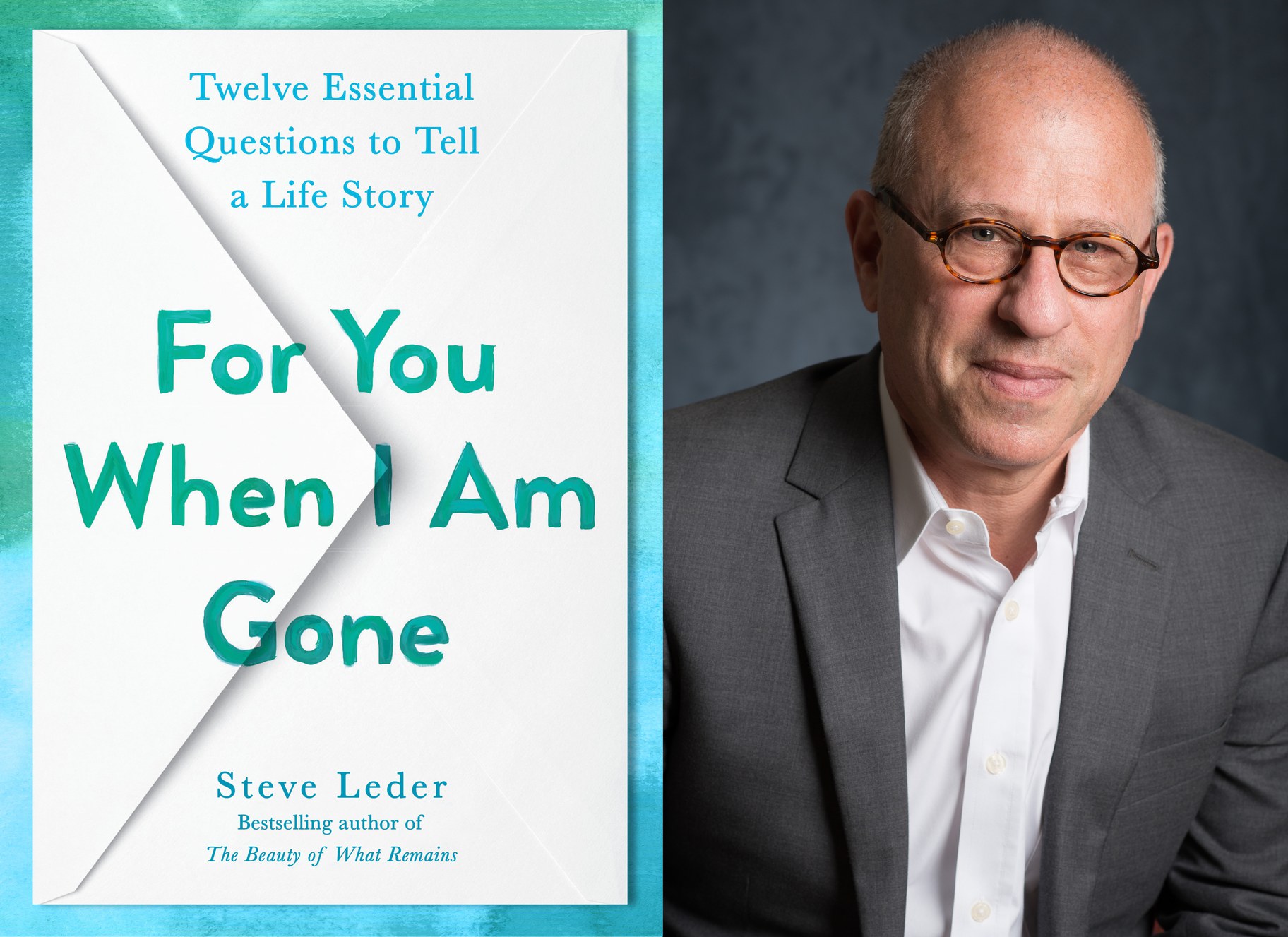

Later, Rabbi Leder discusses his new book “For You When I Am Gone: Twelve Essential Questions to Tell a Life Story” and the significance of writing an ethical will. Leder describes his book as the legacy we want to live and leave to the ones we love.

“It’s not stuff that's going to carry them through without us, it's our life lessons, it's our values, it's our blessings, it's our guidance, it's our words,” he says. “Our words will be cherished far more than any material item.”

Rabbi Leder leader suggests that a tragedy like the one in Uvalde serves as an opportunity and time for introspection, especially when there is something in your life that you regret not doing, such as seeking help when you needed to.

“The opportunity they regret is that they did not get help for their mental health challenges until they had suffered for far too long and done too much damage to themselves and too much collateral damage to others,” Leder says.

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.

He explains that ethical wills are ancient traditions. Jews have been creating ethical wills in Italy and France since the 11th century. They come in the form of a letter and often include stories, joys, and regrets, serving as a way to remember a loved one who is gone and their legacy of how to live a better, happier life.

Book cover “For You When I Am Gone: Twelve Essential Questions to Tell a Life Story.” Rabbi Steve Leder. “There is absolutely no one who suffers pain better alone,” says Rabbi Steve Leder. “We need each other. The rabbis of the Talmud said the prisoner cannot free himself, we have to reach out.” Photo by Lesley Pedraza.

Leder has helped thousands of people write their own ethical wills, and has led workshops around the country that begin with a series of questions: “When was a time you led with your heart instead of your head?” and “What did you learn from your biggest failure?” Each letter is different, and, Leder says, “the most poignant are the ones where the author is honest about their flaws and their regrets, and vulnerable enough to share it.”

Leder recommends not putting this off. “Don't wait to ask yourself these questions to examine your life, to change your life, to make it more beautiful and more meaningful, and to bequeath all of that meaning and beauty to the people you love.”

He also shares excerpts from his own ethical will to his children Aaron and Hannah: “I used to love to dance, but when I became a more public person, I stopped dancing at weddings and parties. I allowed my fear of what others might think of me, fear of being a spectacle, to keep me from dancing. I regret that now. It was a bad example to you and robbed me of joy. Don't let fear of what others might think keep you from dancing or singing or loving.”