Imagine a therapy session — not the modern, virtual variety conducted via phone or Zoom, but rather one where the patient lies back on a couch and the therapist sits behind, listening and engaged. It’s a classic visual made famous in Hollywood films and in TV series like The Sopranos.

While free association and contemporary psychotherapy have evolved past the traditional couch setting, it’s important to acknowledge the origins of psychotherapy — that is, “talk therapy,” belonging to the renowned yet controversial neuroscientist, Sigmund Freud.

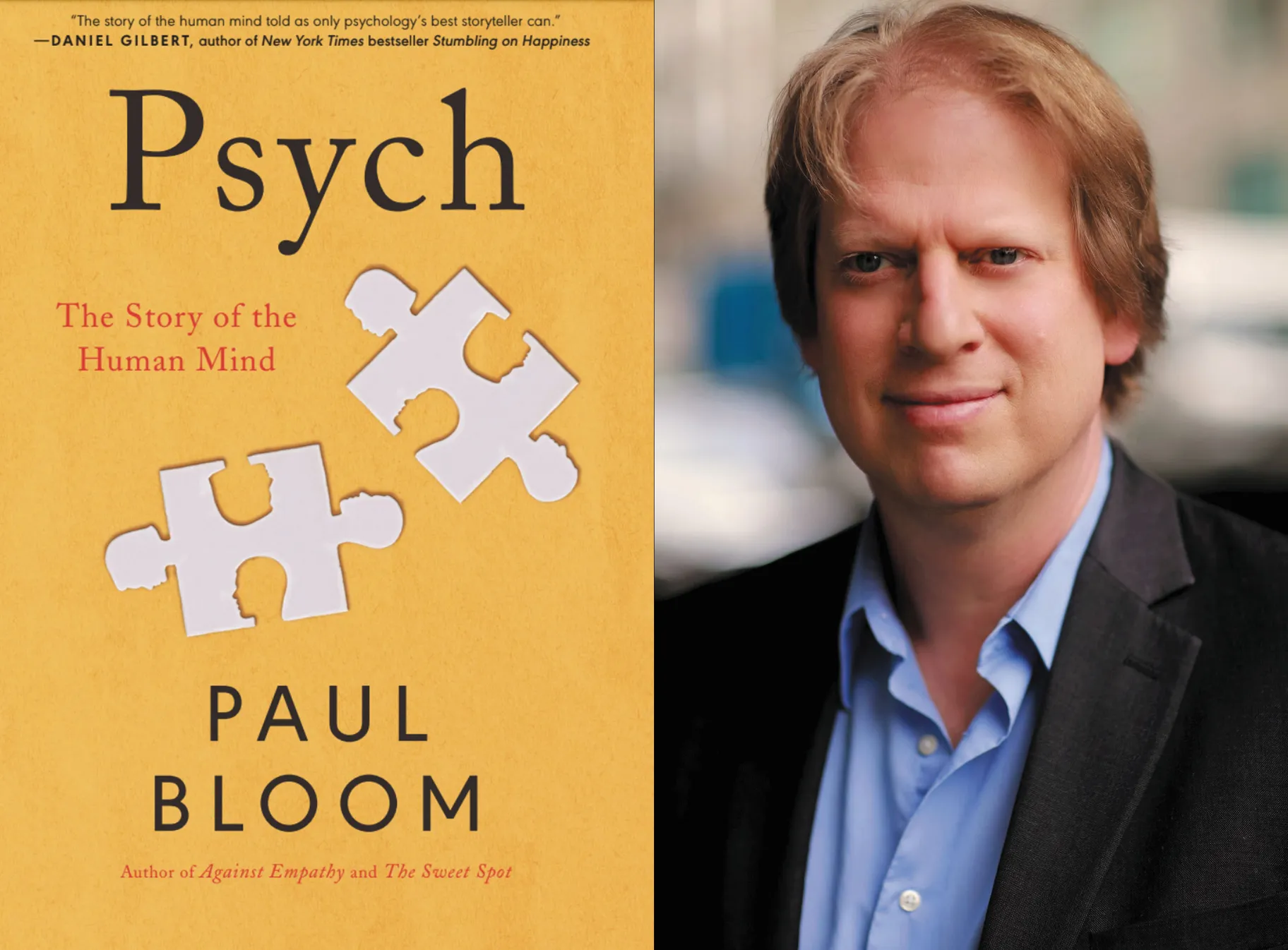

Born in 1856, Freud qualified, practiced, and spent his life in Vienna before moving to London in 1938 after the annexation of Austria by Hitler and the Nazi party. Despite his Jewish heritage, Freud was ardently anti-religious, says Paul Bloom, Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto and the author of Psyche: The Story of the Human Mind.

“He was controversial in Germany at the time [in part] because of his Jewishness,” says Bloom. “His views were seen as deeply subversive, designed to sort of destroy the Christian edifice of morality. … Taking away the anti-Semitism, it's not a bad summary of Freud — he wanted to shock us. He told us things we'd rather not hear.”

Despite Freud’s revolutionary impact in his era, his contemporary influence has diminished and many students are unfamiliar with his work.

“To some extent, modern psychologists see him as if we're sort of a pharmaceutical company that got its start by selling meth,” Bloom explains “Freud is an embarrassment, with his florid claims about penis envy and the Oedipal complex, his bizarre personal interactions, [and] his cult-like following, and now we're a science, so we want none of him.”

It is unfortunate, perhaps, that Freud remains best known as a sex-obsessed psychoanalyst, whose theories on dream interpretation, oral fixations, and phallic symbols have long been debunked, as it detracts from his significant impact on psychology today. Bloom explains that “we get some glimmers of truth in Freud” as he had “the view that we live a life at war with ourselves, where we have all of these psychological systems designed to keep forbidding stuff from rising into consciousness.”

Bloom argues that what Freud established was the very “bread and butter” of modern psychology, namely the idea of a “dynamic unconscious.” Freud recognized that “we're not rational computers making our way through the world by making the best decisions in our own interest. Rather, there's this inner turmoil, a lot of which goes beneath the surface.” At the time, Freud’s claim that “we don't know why we feel what we feel” was considered radical and shocking.

While we may think we have a story for why we do the things we do, Bloom explains that Freud would counter, “Why should we believe your story? Your story is a story, but there's true forces that guided you to do what you do, to love who you love, that you were just unaware of.” According to Bloom, the pivotal concept of “unconscious processes rules us, is important and significant.”

Bloom, who shares some of Freud’s legacy in the field of psychotherapy in his book Psyche; The Story of the Human Mind, compares Freud’s view of humans as “unique” and “complicated” to that of another famous psychologist, B.F. Skinner. Skinner was the founder of “behaviorism” and saw humans as “just rats in a more complicated environment.” Bloom explains Skinner’s view that “there’s no coherent sense of talking about the complexity of the mind, because there is no mind.” Skinner’s theories that “the same psychological processes that could explain the behavior of rats and pigeons could explain the behavior of humans,” ultimately turned out to be a disaster, but very much like Freud, Skinner demonstrated “enthusiasm” and “willingness to take an idea and push for it.”

What surprises Bloom the most is how “stagnant” advances in psychology have been over the last 30 years. Not much has changed with regards to treatment for even severe conditions like schizophrenia, he notes. “We don't know what to do about it, we can't cure it,” Bloom says. “You would have thought that we would have made more progress, but we haven't.”

Despite the relative lack of progress, Bloom is optimistic. “It's fun being part of young science,” he says. “Our field is so wide open that a smart undergraduate could make a discovery, they could transform everything, and I just find that so exhilarating.”

Freud “was a clinician spending so many of his hours working with patients and trying to figure out what was going on with them. This tremendous and brilliant polymath, who started his field of psychoanalysis, developed pretty much what you'd call a cult following and had complicated and often immoral relationships with the people he dealt with. There's no figure now there's anything close to Freud, either in influence or in scope,” says professor of psychology Paul Bloom. Photo by Greg Martin. In Psyche: The Story of the Human Mind, author Paul Bloom provides a comprehensive overview of the field of psychology and explains that Freud’s “obsession with sex is bizarre and inappropriate…but at the same time, there's something sort of socially positive about his obsession with sex, because he argued that everybody is in some sense, a pervert and if everybody's a pervert, nobody's a pervert. His obsession with sex, I think, made the world a little bit better for people whose sexual desires were themselves not typical.”

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.