When it comes to making those big decisions in life, we’re often racked with uncertainty. Algorithms and apps analyze data and tell you how to beat traffic, which books to buy, what music to listen to, and even who to date. But if you’re single, for example, and thinking about getting married or having children, the decision can be daunting. And when it comes to a career path, it can feel like the job or assignment we take can define who we are and what we’ll become.

Making a list can help clarify the pros and cons, but how can we evaluate something for which we have no real first hand experience? Who we aspire to be may change over time, and a meaningful life may not always follow the conventional road map.

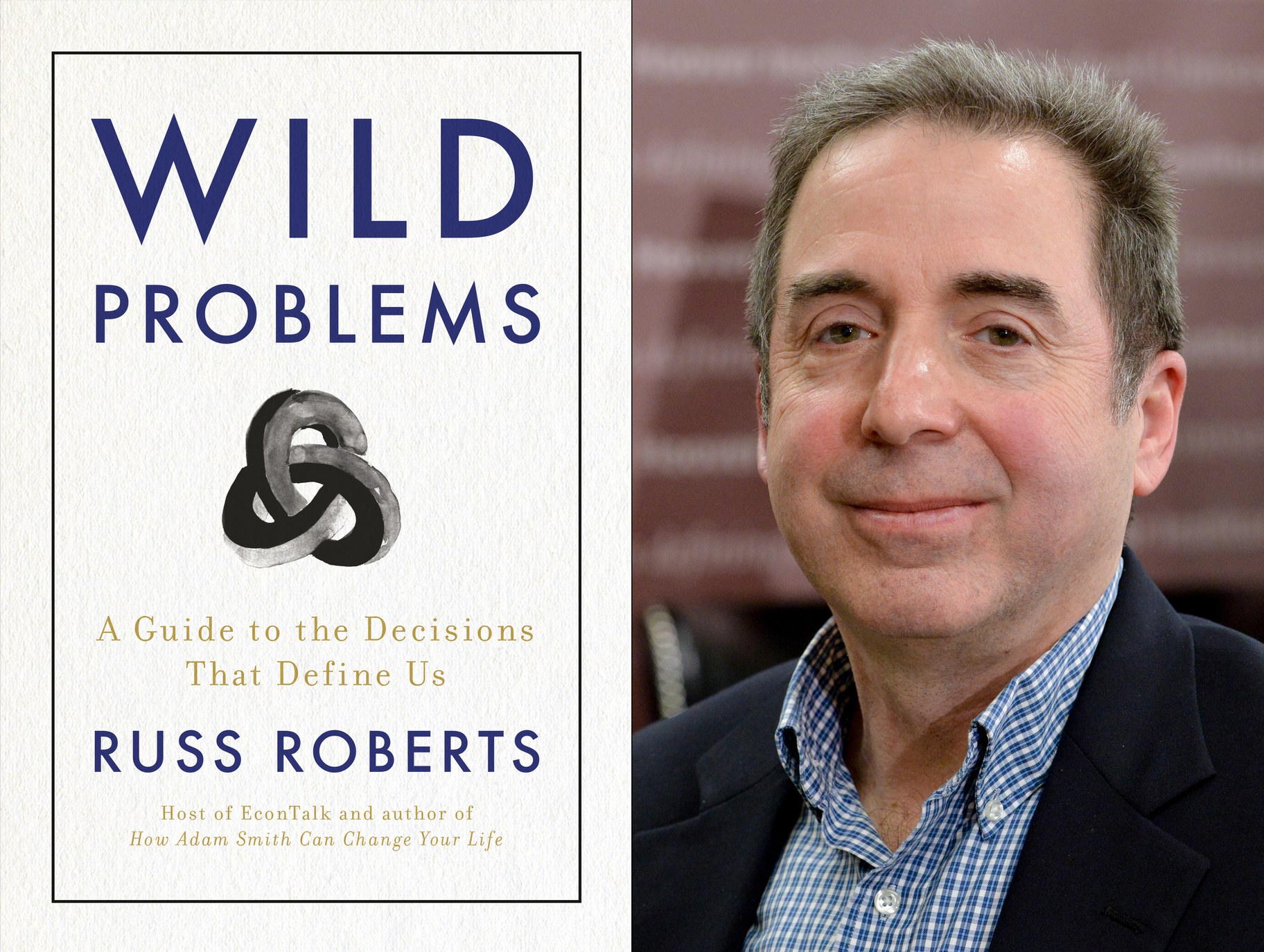

In his latest book “Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us,” economist and author Russ Roberts navigates the decision making process when it’s hard to crunch the numbers. He draws on the experience of great artists, writers, and scientists of the past. For example, at the age of 29, Charles Darwin thought marriage for him was a bad idea; the negatives far outweighed the positives in his eyes, but he eventually talked himself into marrying despite his own cost benefit-analysis to the contrary.

“How could a great scientist make what appears to be an irrational decision in the calm, sober, somber light of contemplation?” asks Roberts. “He looks ahead to marriage and thinks ‘bad deal.’ He does it anyway. Was he irrational? I suggest he wasn't irrational. He realized, presumably, that his pro-con list did not capture everything there was to know about marriage.”

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.

Roberts suggests that for many of life’s big problems today, there are no easy answers, while for much of human history, “your choices were extremely limited,” he says. “Life was much more constrained. Your choices were circumscribed in all kinds of ways, by culture, by law, through religion and other forces that acted on people. … We live in a time now where things are not decided the way they once were, they were up for grabs.”

Book cover for “Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us.” “What's important to you is going to change, and you should leave yourself open to that change. You should look at it, you should observe it, you should experience it, you should taste it,” says economist Russ Roberts. Photo by Jay Mallin

Roberts addresses the challenge that many of us fear — that of regret: “What if we make a choice and it's the wrong one? We will end up down a path that we can't recover from.”

He suggests a different perspective on viewing big decisions and overcoming uncertainty.

“Think of your life more as a work of art and less as a problem to be solved, an equation to be maximized,” he says. “It kinda takes some of the pressure off.”

Jonathan Bastian talks with Roberts about writing his book and Roberts' own recent life decision to move to Israel to become president of Shalem College in Jerusalem, which he describes as “on the surface a crazy career change for me … toward the end of my career.”

“You don't have to be so afraid of making what you might fear is a mistake,” he says. “It's okay, you'll learn from it, you'll see some territory you didn't expect to see, you'll have some adventures you didn't expect to have.

“I use the metaphor of being a tourist: Some tourists make an intense itinerary of the hour — where they're going to be, how long you're going to spend in this museum — they want to make sure to see everything. A different attitude is to be … a flaneur: I'm an explorer, I'm going to walk around, I'm going to find what speaks to me, I'm going to taste before I decide in advance what's best for me”