Everywhere in the world, stories of food and cuisine are also stories of culture and politics. For Taiwan, a verdant island at the far western edge of the Pacific Ocean, politics are threatening to drown out everything else. For years, Taiwanese American freelance journalist Clarissa Wei has been telling Taiwanese stories and introducing the people and the food of the island nation to everyone else. Her book, Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation, is finally here and has been receiving plenty of attention.

KCRW: Congratulations on the book. We've been waiting for it quite eagerly.

Clarissa Wei: Thank you so much. It's exciting to see it come out in the world after years of just thinking about it.

You grew up here in LA, in the San Fernando Valley with apolitical parents. Your schoolmates were from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Did you think very much about your unique identity when you were growing up?

Not very much. Growing up in LA, we really just identified as Asian Americans. When people asked us to clarify what part of Asia we were from, I said Chinese because it was easier to explain to outsiders what that was. A lot of people don't really care to go into the nuances. It wasn't until I became an adult, where I really decided to clarify that.

Did you travel back to Taiwan very much throughout your life? Did your parents take you as a child?

Absolutely. They missed the food of Taiwan, so we would go back every single winter break just to eat food. It was a two-week vacation where my parents would hop back and forth to the stalls that they grew up with. My mom would always go for eel noodles. My dad would always go for braised pork over rice. I loved braised pork over rice or turkey rice. Anything hearty draped over rice was my absolute favorite.

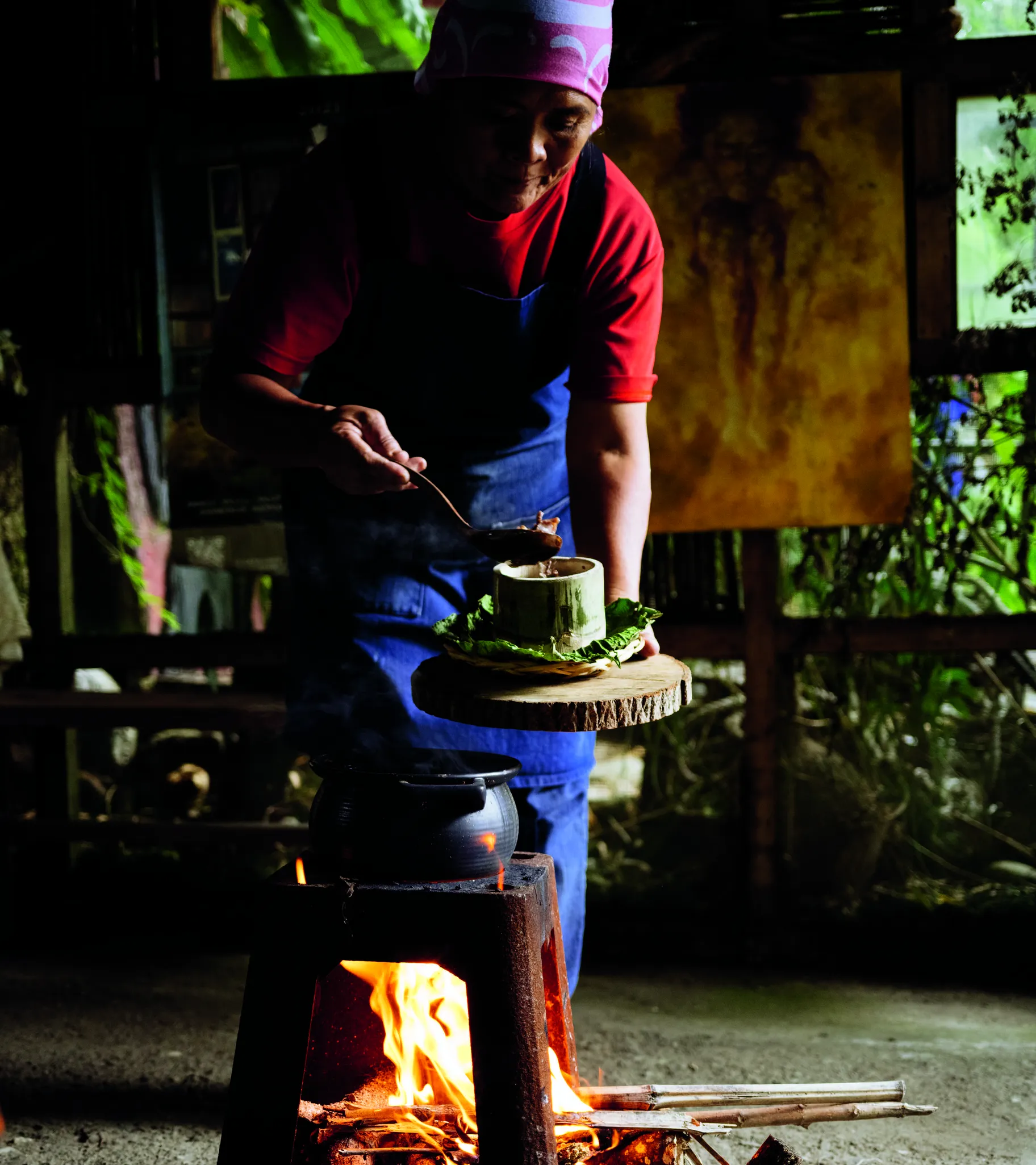

While its roots in China have shaped Taiwanese cuisine, the food ultimately revolves around ingredients that thrive on the island nation. Photo by Yen Wei and Ryan Chen.

How is Taiwanese food culture being redefined now, in the face of tensions with China?

This idea of a distinct Taiwanese food culture started in the 1980s and '90s, when Taiwan transitioned to a democracy. When a place becomes a democracy, people begin to think about what makes them unique. But obviously, as a lot of people are aware, tensions have been at an all-time high. Since 2020, we've had regular incursions by the Chinese Air Force into our air defense zones. We get 15,000 cyber attacks every second. It's like being in a pressure cooker. The more tensions there are, the more aggressive China becomes and, naturally, the more aggravated people here [in Taiwan] are.

One of the ways people look to set themselves apart is through identity. So if you look at recent surveys, 62.8% of people [in Taiwan] identify as solely Taiwanese. Only 2.5% identify as solely Chinese. The numbers in between are people who identify as Taiwanese and Chinese or who didn't respond. But 30 years ago, in 1992, the numbers were completely flipped. Only 17.6% of people identified as solely Taiwanese.

Food is a natural part of a place's identity. So you're seeing restaurants and chefs, and in particular, fine dining restaurants where storytelling is a natural part of the marketing, focusing on ingredients and dishes that are endemic or native to Taiwan. It's very subtle. People are pointing out, "This is pineapple from the south of Taiwan," or, "This is milkfish from this city." Before this democratic transition, before this awareness that Taiwan is its own self-ruled Island, dishes were very Chinese in origin.

What are some of the influences that have come together to create Taiwanese food culture?

There are two major ones that I usually point out — Chinese, obviously (the majority of people here in Taiwan have Chinese ancestry) and Japanese.

So with Chinese, there are two major waves that have had a big impact on our food culture. As everyone knows, China isn't a monolith. You have to look at immigration patterns here in Taiwan. There are the Chinese who came over 200 years ago. That's when my family came to Taiwan. Then there are the Chinese who came post-1949. Those two waves have very different food cultures. The first wave, they came from southeastern China. It's a lot of seafood, lightly seasoned food and minimal food. The second wave, they came from all over. That's where you get the dumplings, the rich bean paste from Sichuan, the noodles and much more diversity.

Then we had the Japanese. Taiwan was a Japanese colony for about half a century, and they monopolized all of our key industries. So the way that Taiwanese soy sauce, rice wine vinegar, and all of our main pantry items are made today, they are made in the Japanese fashion.

I would say those are the major influences. Then we have American because during the Cold War, America gave Taiwan billions of dollars of economic aid and flooded the island with wheat and soybeans. There was this love for American culture, which you can see in a lot of the restaurants today. We have hamburgers for breakfast.

For the last three centuries, and at the expense of the indigenous population, Taiwan has been a land of immigrants influenced by people from around the world. Photo by Yen Wei and Ryan Chen.

Tell us about this distinct, wheat-based culture that grew out of US donations to the island.

In 1954, the Eisenhower administration started this program called Food for Peace. This wasn't just directed to Taiwan, it was directed to a lot of countries around the world. It was said to be far better than a bomber in competing with communist influence in the developing world. What that meant was that they would give food to places like Taiwan to convince them that it was better to be pro-American, pro-democracy than pro-communism. And it really worked.

They sent chefs here to America to learn how to bake. There were these slightly problematic ad campaigns where people in Taiwan were told that eating wheat would lead to better health, better frames, they would be taller and healthier, like the Americans. For the first time ever, people here got a bunch of wheat.

In Taiwan, we are a rice-producing country. Most people did not know how to work with wheat. It was really the refugees who had just come from China, who had just come from all over in the 1950s. Those who came from the north of China where they grow wheat, started making noodles and dumplings. Then you started seeing bread come out because of this program where they sent bakers over to America. Today, wheat is a very big part of our culinary repertoire even though the majority of wheat that we get here in Taiwan is still imported from the United States.

I love how in the book, you create a list of dishes that exemplify certain historical eras in Taiwan. Can you give us a couple of examples?

In the book, I break down the different waves of colonization and governance. One of the main ones is an oyster omelet. That came when a Chinese pirate landed in Taiwan and took over influence from the Dutch. He used oysters (which grow really well in the brackish waters off the coast of the island) and sweet potato flour (sweet potato is a tuber that grows like a weed here in Taiwan) and combined them with a little bit of egg. I love the story of this dish because it really represents the type of humble ingredients that were around at that time.

Then, we can go to beef noodle soup. That happens in post-1949, when a surge of Chinese refugees came to Taiwan. They came with a nationalist government during the Chinese Civil War. A lot of people, if you ask them about the history of beef noodle soup, might say, "Oh, it came from China." But when I was doing my research and interviewing people, I realized that it's actually a dish that is made in Taiwan and combines the influences of different Chinese refugees.

People from the north are really good at making noodles. That's where the noodles come from. People from Sichuan province in China are really good at making spicy fried bean paste. That's where the foundation of the broth comes from. The beef comes from people who did not eat pork, who were halal. That comes from northwestern China. Keep in mind, beef was taboo in Taiwan for centuries before these people came. The art of making broth and braising, that's an influence that came from southeastern China. So you have all of these refugees coming from all of these different parts of China. They combined their techniques and out came this dish that they made in Taiwan, beef noodle soup.

Last but not least, I love talking about the American influence because I think that's something that a lot of people overlook. They think it's some tacky fusion but it's been around in Taiwan for a while. In the 1960s and up to the '90s, there was this love for American culture. That's where Taiwanese popcorn chicken came from, it was inspired by American fried chicken. We have steak with spaghetti at the night markets. That's a very Taiwanese night market dish. That was inspired by American-style steak houses. So we have three very different dishes but all very Taiwanese.

When asked her nationality growing up in the San Fernando Valley, Clarissa Wei often said she was Chinese rather than explaining the nuances of her Taiwanese heritage. Photo by Ryan Chen.

What is the category of rechao?

Rechao is what I call "beer food." Rechao means hot stir fry. Think short tables, big walks on the street, and plates of greasy, delicious food like fried rice and clams with basil. This is a genre that really took off in the 1990s, during the height of Taiwan's economic prosperity. It's a genre that's quite unique to Taiwan. It's a combination of a lot of things. It's a combination of Chinese food, it's a combination of Japanese food. There are a lot of dishes in there that you can't find anywhere in the world.

My favorite one is shrimp with pineapples and sprinkles on top. They take deep-fried shrimp, coat it in a sweet mayo similar to Kewpie mayo, serve it with pineapples on the side and add sprinkles on top. It probably sounds a little bit weird to anyone who hasn't had it, but it's a very classic dish. I think it embodies the diversity of ingredients. We have seafood and people here love sweet flavors because Taiwan was a sugar-producing colony of Japan. We're a tropical country and pineapples are a huge influence. So rechao is sort of where my friends and I go to decompress. Instead of walking through a night market, which can be really miserable when it's hot, especially when there are a lot of tourists around, we'll just sit down and have plates of fast stir-fries and food and a lot of beer.

That sounds wonderful. Here in LA, many eaters are probably unaware of how much Taiwanese food they're eating. Do you want to name check a couple of places that you love?

Pine & Crane. A lot of people in LA know about it. I think that's a really good place to dip your toes in Taiwanese cuisine. They have dishes that are quite unique. They have a fried egg with preserved turnip. Preserved turnip is very traditional to Taiwan. They also have braised pork over rice and beef noodle soup.

Another place that has been around since I was a kid is in Arcadia. It's called SinBala. This place has quite esoteric dishes. You really have to look through the menu to find them. They have an oyster omelet, which is very rare in America. They also make a fantastic Taiwanese sausage. Taiwanese sausage is sweeter, a little bit heavier on the five spice and it's usually served with raw garlic, which is confusing for a lot of people. For me, that's a comfort pairing. Every time I go back to LA, even though I live in Taiwan, I'll still order SinBala because I grew up with it and it reminds me of being American Taiwanese.

In Made in Taiwan, Clarissa Wei breaks down recipes into different waves of colonization and their culinary influence. Photo courtesy of Simon Element.

Beef Noodle Soup

紅燒牛肉麵

Hóng Shāo Niú Ròu Miàn

Serves 4

This recipe is my adaptation of the one that chef Hung gives to his students. He prefers a pure beef bone broth base, but notes that the variations are endless because every restaurant has their own secret recipe. Hung says the key is procuring a really high-quality cut of beef, making a flavorful broth, and everything else is just an accessory. “When you’re making beef noodle soup, the only competition is yourself, not other chefs,” he stresses.

Ingredients

- 2 teaspoons coarse salt

- 2 pounds (900 g) whole boneless beef shank

- 1 tablespoon canola or soybean oil

- 1 1-inch piece fresh ginger (10 g), unpeeled and sliced

- 4 scallions, white and green parts separated

- 3 garlic cloves, smashed and peeled

- 2 tablespoons coarse raw sugar, such as demerara

- 1 1⁄2 tablespoons dried fermented black beans (dòu chˇı 豆豉)

- 1 1⁄2 tablespoons fermented broad bean paste (dòu bàn jiàng 豆 瓣醬)

- 8 cups (2 L) Bone Broth (page 357, but use beef bones instead of pork) or low-sodium chicken broth

- 1⁄4 cup plus 1 tablespoon (75 ml) soy sauce

- 1 Spice Bag (recipe follows)

- 1⁄2 pound (225 g) daikon, peeled and chopped (optional)

- 1⁄2 large carrot (50g), peeled and chopped (optional)

- 1 large tomato, quartered

- 1 yellow onion, peeled and halved

- 1⁄2 pound (225 g) Taiwanese bok choy or regular bok choy, chopped into 1-inch (2.5-cm) segments

- 1 pound (450 g) fresh wheat noodles or 7 ounces (200 g) dried wheat noodles

- Fresh cilantro sprigs (for garnish)

Instructions

-

Rub salt evenly all over the beef shank. Cover the beef and let it rest for at least 2 hours or overnight in the refrigerator. This will tenderize and draw out flavor from the meat.

-

In a large pot, combine the beef shank with enough water to cover. Bring the water to a rolling boil over high heat. Reduce the heat to medium, and simmer for 5 minutes. Turn off the heat. Drain and transfer the beef to a colander in the sink. Rinse the beef under cool running water to get rid of any scum. When the beef is cool enough to handle, chop into bite-size 2-inch- (5-cm-) thick chunks.

-

Set a large pot over medium-high heat and swirl in the oil. When the oil is hot, add the ginger, the white parts of the scallions, and the garlic, and cook, stirring often, until aromatic, about 20 seconds. Add the sugar, fermented black beans, and fermented broad bean paste, and cook, stirring, until the sugar begins to melt, another 30 seconds. Immediately add in the beef shank, mixing continuously with a wooden spoon to make sure the shank is coated evenly with sauce, about 1 minute.Pour in the bone broth and soy sauce, then add the spice bag, daikon, carrots, tomato, and onion. Cover the pot and bring the soup to a rolling boil. Reduce the heat to low, and slowly simmer with the lid slightly ajar

until the beef is fork-tender, 11⁄2 to 2 hours. -

Fill a medium pot with water and bring it to a rolling boil over high heat. Quickly blanch the bok choy for 30 seconds. Ladle it out with a spider strainer and set aside for later.

- In the same pot of boiling water, cook the fresh wheat noodles until al dente, about 3 minutes. If using dried noodles, cook according to package instructions. Turn off the heat and drain in a colander. Rinse immediately under running water and shake to dry.

- Check the meat; the beef is done when a knife can pierce through the meat with little to no resistance. Turn the heat off. With tongs, pick out only the beef chunks and set aside. Strain the broth through a fine-mesh sieve into a clean pot, discarding the spice bag, the aromatics, and vegetables.

- Mince the scallion greens. Divide the noodles among serving bowls. Arrange a handful of beef and the bok choy on top of the noodles and ladle the hot broth over. Garnish with the green parts of the scallions and cilantro.