Gelatin seems to be everywhere these days. From TikTokers devotedly sharing midcentury concoctions to culinary artists creating elaborate cakes, it involves all manner of flavors and ingredients, held in suspension. In his latest book, The Great Gelatin Revival, prolific author and food historian Ken Albala looks back at how our embrace of gelatin has waxed and waned over the years, and he explains how he earned the nickname "Jiggle Daddy."

KCRW: So what changed your mind about jellies? Who were you around that made you want to look at gelatin in a different way?

Ken Albala: Honestly, it was a dare. I'm on Facebook far more often than I should be. A friend of mine there said, "Why don't you take a look at this group on Facebook called Show Me Your Aspics?" I thought, no, I can't do that. That looks terrible. I, of course, thought the worst of it. Then I went on and saw that people were making these interesting shapes with flowers in them and very interesting flavors and colors. It wasn't just retro kitsch, either. I thought, well, let me just make one. Let's see what happens.

I literally went into the cabinet, pulled out whatever I had, which happened to have been ouzo, which is wonderful. I was expecting maybe it would turn out cloudy. It didn't, which was really surprising. It turned into this beautiful little sphere of what looked like glass. I thought, this may be fun. Why not use other types of alcohol? Why not put in good ingredients and not use the pre-flavored Jell-O packet. It just turned out to be a lot of fun. I like playing in the kitchen. So one Jell-O became another one and another one.

I posted my findings in that group and they seem to love it, to such an extent that they declared at one point that I would be their "jiggle daddy." I embraced that, for reasons I don't know why. And for about a year, I pretty much [made] a Jell-O or more every single day.

A tower of cantaloupe with roast duck and celeriac salad spritz is a three-course meal in one. Photo by Ken Albala.

You ended up serving that sphere of ouzo gel that you made with feta, kind of like a Greek salad with its own alcohol accompaniment.

That's exactly right. Everything in the book that I created — this is not the history part of the book but the future prognostications of the revival — they're all things that would normally go together anyway, if you were having a cocktail and some interesting snack beside it. It's just that I put it in the Jell-O and made the Jell-O alcoholic.

Let's talk about different types of gelatin and what your preferred type is.

Historically, gelatin can be made out of any kind of collagen, meaning coming from animal or even plants — seaweed mix, agar agar, carrageenan. I don't like them very much because they don't bounce and jiggle the way Jell-O does. But you can make proper Jell-O out of the swim bladder of a sturgeon, which is isinglass. That was really the dominant one in the 17th, 18th and up into the 19th century. I think the disappearance of sturgeon meant that other forms had to be found. You can make it out of hartshorn, which is the antlers of young deer. You grate it directly into hot water and it dissolves. So there's a lot of different ways. It can be made from skin, it can be made from nubbly bits and cartilage.

The most typical and easiest way is, of course, with feet. Calves' feet, pig's feet and sheep feet have tons and tons of collagen in them. All that connective tissue just melts and becomes a Jell-O.

I like the unflavored kind of Jell-O. I have made it from scratch and it does kind of taste like whatever you make it from. For ease of preparation, I use the unflavored gelatin packets. We use the sheets, which are more common in professional baking. Those have no flavor at all. You just dissolve a little bit in cold water. Then you add hot water or you heat up the alcohol or whatever you're mixing and throw it in. It's like five minutes. It's pretty much the easiest dessert that you could possibly make if you're starting with a packet.

A mashup of two classic dishes named after the Roman emperor, the Caesar Caesar combines elements of a salad and a cocktail. Photo by Ken Albala.

Let's talk about aspic, the savory, clear jelly made from meat or fish stock. A lot of people, even chefs, find it disgusting.

Well, think of the generation when we grew up. I'm talking about in the wake of the post-war baby boom, when everyone embraced technology and thought bright colors and flavors and instant Jell-O is exactly what we want for our houses, the Beaver Cleaver generation. The generation that followed was into whole foods and natural and local and sustainable. That list goes on and on. But we really didn't want to eat things that are artificial.

I think everyone in our generation, certainly the tail end of the Baby Boomers, saw Jell-O as the most artificial, the scariest, the worst possible example of industrially made food, even though aspic doesn't have to be that way. There are very elegant aspects. I think it put a bad taste in the mouths of most people. They looked at the abominations of mid 20th century Jell-O, and said, "That's the last thing we want to eat. We want good traditional peasant fare."

We may think that pattern is a weird quirk of the mid-20th Century but it is replicated as far back as historical records go. There are periods in history where people embrace the bright, the new, the technological, the artificial. And there are those that embrace natural and local and traditional. Almost without fail, the ones that love technology are Jell-O lovers. The 1950s, the Victorian era, the late Middle Ages and Renaissance were also really, really into Jell-O. Those are all its heydays, in fact. They're almost always followed by periods when people look at Jell-O with complete revulsion and disgust.

Cold noodles and gelatin are two ways to cool down and this purple mung bean noodle and mango number has a tropical twist. Photo by Ken Albala.

I love savory aspics when they're beautifully made. It's such an interesting way to consume meaty flavors in a way that is cool and has almost no texture as it melts in your mouth. So convince us with a savory application. What is one of your savory jellies?

Well, there are a few that I like a lot. I think the one that I'm going to be making for the rest of my life, just because it turned out so well, is imagine what your favorite cocktail is. Mine happens to be a Boulevardier, which is bourbon, Campari and vermouth. It's sort of like a Negroni but it's made with bourbon instead [of gin]. Imagine that but instead of in drinkable form, in solid form.

Think of the fall flavors that go with that. Imagine dried fruits and nuts. Put that together as a bar, not as firm as a gummy bear but not loose like a Jell-O, so when you bite down, you actually get some crunch and chew. As you're doing this, the flavor of bourbon and dried fruit is transporting. It's a beautiful flavor and something that I'd be happy to eat anytime. There are a lot of things like that in the book.

Just yesterday, I made us a ceviche with vegetables, raw fish and lime juice. I thought, let's put tequila in this, it makes perfect sense, and solidify it as Jell-O. When it's very hot out, it's really refreshing and acidic and pleasant. And you get a nice little hit of alcohol out of it as well.

A gelatin Fruit Loop negroni makes for a colorful nightcap. Photo by Ken Albala.

The first recipe in the book is for gin and tonic jigglers. You say to serve them in a dark room with the black light. Why?

Most people don't realize that quinine is actually fluorescent. If you shine a black light on it, it lights up in a really interesting way. Imagine the wonder of pulling out a cocktail, and you can do it with a regular gin and tonic. (Use a good tonic that has a lot of quinine in it.) But if it's solid and you turn the lights out and you have an interesting pattern on it… I used a bottle of red palm oil from Africa that had this interesting diamond pattern on the bottom. It kind of looks like HAL, the robot that takes over in 2001: A Space Odyssey. I shone a light down onto it, and I thought this is the coolest thing. Then I ate it.

You've documented some gelatin dishes from other places in the world. Could you talk about the kohakutou?

Kohakutou is a Japanese form of gelatin that's made with agar. It has so much sugar in it that it actually crystallizes and becomes crunchy on the outside and soft on the inside. When it's sold in Japan, it looks like shards of colored glass that's broken and magnificent. What I was trying to do was get some alcohol in there, which I thought might mess with the chemistry of however this works. But I did it using some Sauvignon Blanc. I hung them up outside and let them dry, and they were, indeed, crunchy. It felt like eating icicles or crystalline forms. They were delightful.

This bullshot gelatin with marrowbone shortbread and pickled lemon was inspired by a 1980s cocktail. Photo by Ken Albala.

And they look beautiful. They look like chimes.

Yeah, I hung them in my backyard, my bamboo grove here in Stockton.

You also go so far as to share a recipe for probiotic gummies made with a vegetable brine.

This is actually my favorite drink. It's called Şalgam Suyu. It's from Turkey. They sell it like if you're going over the Galata Bridge into Istanbul. There'll be people with plastic cups selling this. It looks like it's [made of] beets. In fact, the word in Turkish means "turnip" but it's actually a black carrot that they make it out of. Imagine taking black carrots, garlic, peppers and all sorts of vegetables and pouring water and salt over them and starting the fermentation with a little bit of sourdough bread and chickpeas. You put it in the top of the jar, and it begins to ferment in a couple of days. It's actually easier to do than sauerkraut.

What comes out of this is crunchy vegetables. The liquid that comes out of this, if you're an addict of pickle juice, this is pickle juice to the nth degree. It's salty and sour and spicy and sweet from the vegetables. It's magnificent. I was thinking, why not add gelatin to this in such a way that you get nice little chewy gummies that are sour and taste like pickles? That was the experiment and it worked wonderfully.

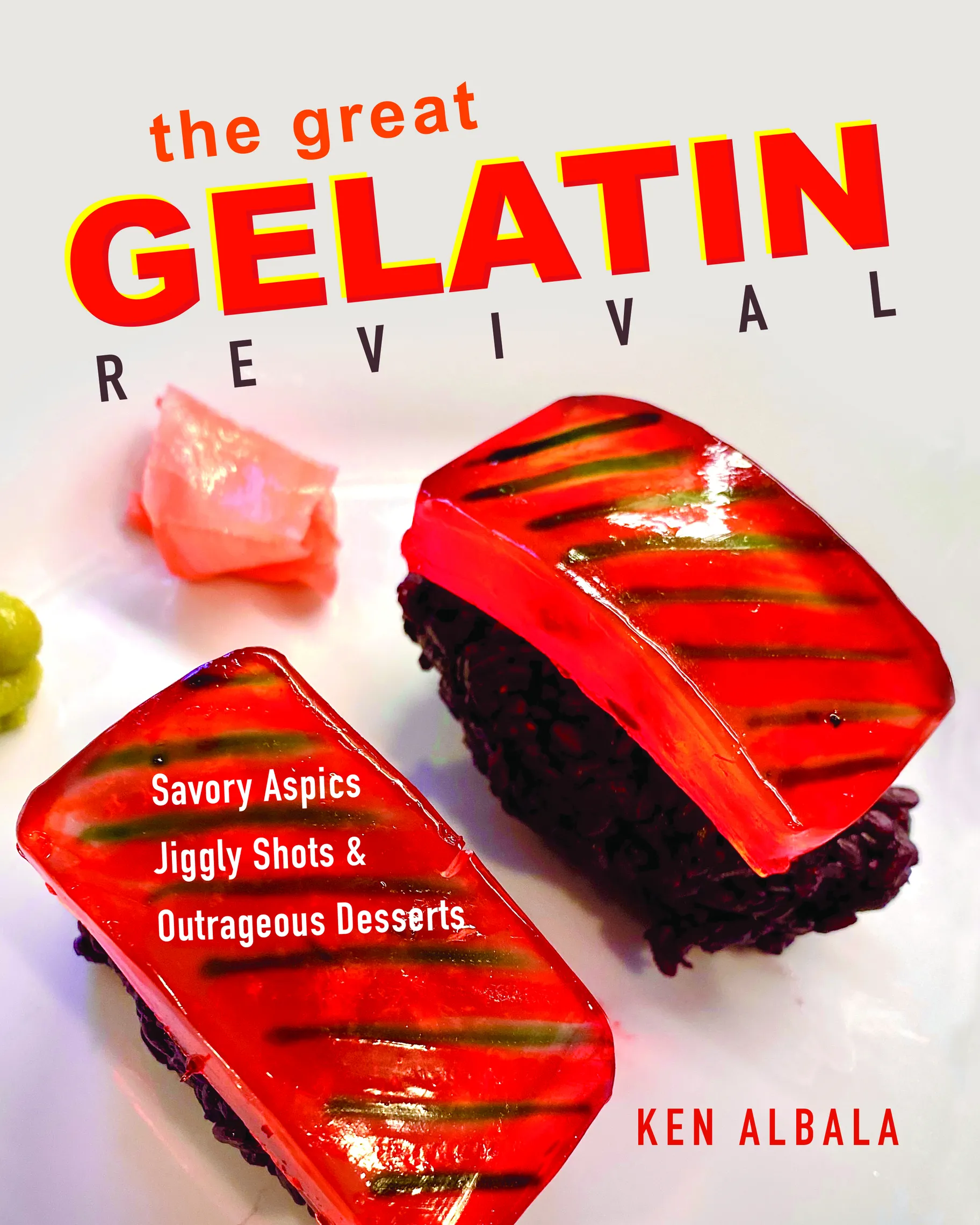

The irresistible jiggle has found its way back into vogue in The Great Gelatin Revival. Photo courtesy of University of Illinois Press.

Gin and Tonic Jigglers

Ingredients

- neutral oil such as canola, grapeseed, or vegetable

- grated zest of one lime

- 1 tsp sugar

- 2 packets unflavored gelatin

- ½ cup gin

- 1 ½ cup tonic water (choose a luxury brand with real quinine such as Fever Tree or Q)

- juice of one lime

Instructions

-

If you can find fun silicone molds in the shape of palm trees, or anything kitschy, all the better, but an ice cube tray works well too.

-

Prepare molds by moistening a paper towel with a few drops of oil and rubbing around mold. Sprinkle in a little of the grated lime zest and a fine dusting of sugar. In a large bowl, dissolve the gelatin in the gin and stir well.

-

Heat the tonic water to boiling. Add immediately to the gelatin mixture and stir well until no longer hot. Place your molds in the refrigerator and then carefully pour the gelatin into the molds. There’s nothing harder than moving a filled mold into the fridge. Let set a few hours until firm.

-

Unmold and arrange on a platter with other hors d’oeuvres. Then shut all the lights off and shine a black light on the jigglers; they’re fluorescent. This jello was set in the bottom of a plastic palm oil bottle, giving it this incredible pattern.