Life is driven by flavor. The seductress that is flavor often leads us down the rabbit hole of food studies. If you run a restaurant or you're in the food business, you know that flavor is power and it needs to hit in the first few bites. But what exactly is flavor? And how do we create it in our own heads? We've been following the interests of Arielle Johnson for years. Her new book is Flavorama: A Guide to Unlocking the Art and Science of Flavor.

Evan Kleiman: When I hear the term "flavor scientist," my mind goes to the industrialized food world. I think of someone working for a big company, like Kraft or Kellogg, who's trying to create the next viral snack or food trend. But that is not what you do. How does your work differ from that of most other flavor scientists?

Arielle Johnson: Most food scientists and most flavor scientists are employed by large food companies, largely because that is who hires people like that and pays for the field to exist. I'm at a little bit of a right angle to what they do. [What I do] intersects in the chemistry and in the sensory science but I'm much more interested in understanding flavor as an everyday experience, as an expression of biology, culture and ecology, and as something to use in the kitchen. So I do apply it but in a different way than it is typically applied.

Are you often contacted by chefs who are trying to create something or push something further, and they need science to help them take a leap?

Often, they don't necessarily know what science they need but they know that I am good at solving problems using science. Often, a chef has been working in one direction or another, maybe trying to do a fermentation project or get a flavored ice to behave a certain way. When I can, which is a lot of the time, actually, I like to step in and try to cherry pick what area — is it biology? is it chemistry? is it molecules reacting? is it volatility or something like that? — and set them on the right path to get what they want.

That must be eminently satisfying.

Incredibly. That's my favorite thing.

What intrigues me about flavor is how personal it can be. I sat across from noted restaurant critic Jonathan Gold each week for a couple of decades, listening to him describe flavor. I would always ask myself, is that how I perceive what he's talking about? Often, in my own mind, it was no, I'm perceiving it differently but how interesting it is, what he's perceiving. Could you speak a little bit about that, the personal nature of flavor?

One of the things I find most exciting and attractive about flavor is that it sits at this intersection of the extremely concrete — it's based on molecules, which we can measure, real matter — and the personal. Flavor doesn't happen until you put something in your mouth and the signals get sent to your brain and then from there, all bets are off. But one important piece to the connection between flavor and the personal, is that flavor is not just taste, it is also smell.

Smell is a huge, essential part of flavor. Smell, more than any of our other senses, is deeply tied in a physical, neurological way to our emotions and memories. Once we gather smell molecules and build a smell signal and pass it to the rest of the brain, the first place that it goes is the limbic system in places like the amygdala, places where we keep our most emotional, personal memories and associations. So with smell, and therefore with flavor, we'll often have our personal history, our emotional reaction to it, come up before we can even recognize or articulate what it is that we are smelling and tasting.

Chefs and restaurants around the globe enlist the help of flavor scientist Arielle Johnson to give them a leg up on deliciousness. Photo by Nicholas Coleman.

It's so interesting to me that these days, on social media in particular, where people are constantly giving their takes on whatever they're eating or the latest restaurant thing, it's always within these parameters of better or worse. Yet I think very few of us have spent the time to actually parse what it is we like and why.

I think that's true. I think science really has nothing to say about questions of aesthetics and taste — taste in the philosophical sense, not the physiological sense. What is the ultimate? What is the best? These are subjective questions. Science can enhance that understanding but can't really tell us what it is.

Let's get into the science. What is flavor?

Flavor is a composite sense, combining mostly taste and smell, as well as some information from all the other senses but taste and smell are the two big ones.

Taste, meaning sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami, is something a lot of people know about but let's focus on smell. In the book, you say, "Right now, as you read this, you have brain cells dangling out of the bottom of your skull, exposed to the air inside your nose at all times, and we all walk around like this is totally normal."

I know that is how it works. I know it's a real thing. And still, every time I think about it, it blows my mind that that is how smell works. We have neurons that are attached on one end to a structure called the olfactory bulb in our brain and then those neurons, those brain cells, pass through small holes in the base of our skull and just kind of hang out, waiting to grab on to smell molecules on the inside of our nasal cavity.

Amazing. You compare smell to a QR code. What do you mean by that?

It's probably best understood by comparing it to taste. With taste, we have very distinct matches between specific molecules, specific receptors, and specific perceptions. When you taste something sour, acid molecules will go onto your tongue. They will interact with the sour receptor, which pretty much only interacts with them and with nothing else, and the signal that gets sent to your brain is like pressing a key on a piano. So sour, loud, and clear. Very simple, very one-directional.

With smell, we don't have a finite set of smells the way we do with taste. We have the five basic tastes. With smell, we have about 400 different types of receptors and the way that we collect smell information is rather than having these one-to-one pairings, like acid to sour receptor and sugar to sweet receptor, all volatile smell molecules can interact with several of these 400 receptors. And any receptor might grab on to a few or dozens of molecules in a different way.

You have some rules for flavor that you list in the book. I think the one that is the most useful for home cooks is the fact that flavor follows predictable patterns, and that if people understand the patterns, they can unlock the ability to improvise. Is it possible to train your palate to become attuned to that?

Absolutely. A lot of people when I'm talking to them and they hear that I study flavor, they're like, "Oh, I have such a bad palate. I could never do that." The fact is that most humans are very, very good at distinguishing differences between flavors, we're just very bad at naming them. Fortunately, we can learn how to do that with practice. Most of us are just out of practice. I've actually, in my academic career back in the day, trained a few dozen people to become very precise analytical tasters. What we do in the lab, you can essentially replicate on a simpler level at home. It's really just a process of smelling and tasting things very carefully, paying attention, trying to name any associations that you have, and then basically doing this over and over again. Most people are bad at it at first and it feels very out of our comfort zones and uncomfortable, but eventually, you will get very good at it.

Let's get into specific ingredients. What is meat?

Meat, from the perception of a flavor scientist, is a mostly flavorless but texturally interesting sponge of proteins soaked full of water with a relatively tiny amount of flavor-active molecules in it.

Those flavor molecules are like precursors and they create a meaty flavor once that meat is cooked.

Yeah, so if you smell ground beef or taste beef tartare from a restaurant or a supplier that is reputable enough to give you raw meat, you'll notice it doesn't taste beefy like beef stew, necessarily, or like cooked meat. That beefy flavor really doesn't exist until you start heating up the meat and the different ions and enzymes and things like that interact with things like cell membrane lipids and free amino acids, stuff that's floating around. Once all these components meet and get shaken up in the heat, they'll make these very beefy flavored molecules. That is the flavor of meat that we know and love.

Objectively, do vegetables have more flavor than meat from a molecular standpoint?

Yes. In terms of raw product, vegetables have a lot more flavors than raw meat. Definitely.

Okay, spice. We're here in LA. You had a burrito for breakfast. Why do different versions of chilies hit differently?

In terms of spiciness, chilies have a very, very spicy molecule in them called capsaicin. The range of spicy in chilies is pretty much a one-to-one correspondence with the concentration of this molecule capsaicin that they make. The weird and fun thing about spicy is that it feels like a taste but it is not actually a taste because we do not sense it with our taste buds. We sense it with a pain receptor. Technically, spicy is a part of touch.

Wow, I love that. For some unknown reason, I have about two pounds of cocoa nibs in my pantry.

Nice problem to have.

You gave me the gift, in your book, of cocoa nib lemon butter. How do we make it and what do we do with it?

Cocoa nib lemon butter is a compound butter. It's a recipe I wrote to highlight and showcase how good fat is as a carrier of aromas. Specifically, any compound butter is really about taking some kind of flavorful solid ingredient, folding it together with butter, and letting it hang out for a little while. With cocoa and lemon butter, you get these deep, roasted fruity notes from the cocoa nibs, some bitterness and also this very light, sprightly, heady citrus flavor from lemon zest. The nice thing about compound butter is that it's easy to make. And by giving these aromatic, flavorful ingredients a chance to hang out with the butter for a little while, you'll get something that is infused with the character of the flavors but also has these intense pops of it. It's a dynamic eating experience that I really like.

It's really interesting. The reason I have so many cocoa nibs is that I really love making biscotti with cocoa nibs. I think I'm going to make that butter and then use the butter in the recipe.

That sounds delicious. That's exactly the kind of thinking I hope people take away from reading about flavor. Basically, any time you're cooking and bringing ingredients together, you have an opportunity to bring them together in a more flavorful, more delicious way. Any time you're adding fat to a recipe, whether it's butter or oil or anything like that, if you combine it with the flavorful ingredients early on, you'll get a much more intense, round, well-infused flavor. Making this compound butter and then using the butter to make the biscotti, I think you'll probably get quite a different taste experience.

Cacao Nib–Lemon Butter

Makes about 1 cup

This is a salty-sweet dessert on some rich brioche or challah. It’s also great on squashes, summer or winter.

Ingredients

- 2 sticks (about 225 g) softened, best-quality unsalted butter (grass-fed and cultured, if you can find it!)

- 2 tablespoons (20 g) lightly toasted, crushed cocoa nibs

- a scant ½ teaspoon (2.5 g) fine sea salt

- 3 g lemon zest (just short of 1 medium lemon, zested)

Instructions

-

In a medium to large bowl, combine all the ingredients.

- Mix together well, then pile on a piece of plastic wrap and roll into a log. Chill, well wrapped, in the fridge until use. Consume within 3 weeks.

Tell me about your Peanut Russian.

The Peanut Russian is my take on a White Russian, which is coffee liqueur and half-and-half. Watch The Big Lebowski. I don't know if people still drink them regularly. I like them a lot. It's this idea of an alcoholic beverage that's got this deep coffee, bitter brown goodness and a lot of creaminess. But in this case, instead of a dairy product, you use peanut milk, which is like making soy milk but with peanuts instead of soy beans. It's extracting all the flavor of the peanut into this creamy "milk" and then using a coffee-infused rum in the place of a Kahlúa to make a really creamy, nutty, also vegan cocktail experience.

It sounds so good to me. Why are you a fond evangelist, someone who goes so far as to cook giant trays of chicken that you're then going to dispose of because you have stabbed it so many times to let the juices flow out and caramelize on the pan?

The fond is, as you say, when you're cooking a piece of meat and the juices leak out, they make this brown layer that sticks to the pan. This, to me, is the perfect concentrated essence of meatiness. Whenever I brown a piece of meat or I'm trying to make gravy or roasting a piece of meat, I always, always, always deglaze the pan and find a way to incorporate the fond, the brown meaty parts into either the meat itself or into a sauce.

During previous Thanksgivings, when we've grilled our turkey and we're not roasting it in a pan, so we did not have a fond, I did not want terrible gravy (I think fond is essential for good gravy) so we roasted sheet pans of chicken drumsticks that I stabbed all over while they were cooking, which you're not supposed to do. You're not supposed to stick your knife too many times into a piece of meat to check because it'll let the juices run out. In this case, I wanted the juices to run out because I wanted them to collect on the pan and make an extra, extra large fond to use wherever I wanted. In this case, [it was] for delicious gravy. In my defense, I didn't actually throw the drumsticks away. I did use them to make a light stock. But in this case, you're really taking that flavorless sponge and separating it from the meat juice, which you get to experience as its own concentrated essence.

Does texture have anything to do with flavor or is it just a bonus?

No, texture is a huge part of flavor. The texture of salt grains, for example, can have a really significant impact on how salty you perceive a salt to be. Things like astringency in red wine. If you drink a young red wine and it makes the inside of your mouth feel like sandpaper, you'll have a bit of a different flavor experience overall than if you were just drinking it without tannin.

Is that because the tannins are actually having a physical effect on the surface of your tongue?

Not on the surface of your tongue. Your entire mouth is lubricated with saliva. (Sorry for saying "lubricated" and "saliva." I know those are gross words.) What makes saliva a good lubricant, in this case, is because it has different types of proteins, sometimes what are called glycoproteins, floating around in it. Tannins, which are groupings of polyphenols that make red wine red and other fruits and flowers the colors that they are, react with the proteins and pull them out of solutions. It'll actually make your saliva a much less efficient lubricant. Astringency is the unmediated feeling of your tongue touching the inside of your mouth.

I love that. It's such a nerd fest. Do you think that one reason why a lot of good restaurant food happens is because chefs take advantage of opportunities to create layered flavor, they take the time to do that, whereas at home, we just want to feed ourselves?

Absolutely. In a restaurant, since you are doing all of your prep in advance and then executing many dishes over the course of a night, the structure is really set up that allows you to pre-make or pre-prep a lot of different components then bring them together on the final plate. I'd say yeah, the biggest difference between really complex-tasting restaurant food and home cooking is this singular focus on making each component as flavorful as possible, often regardless of how inefficient and time-consuming that is.

This is where all of the infusions, extractions, dehydrated situations come into play.

Fermentation, things like that, if you want to start your prep months before you're going to eat a dish.

Like at Noma.

Exactly.

We have to talk about pie because we're kind of pie-obsessed. And specifically apple pie. We have a big contest coming up in a few weeks and there are two apple categories this year. How is the flavor of an apple transformed by heat?

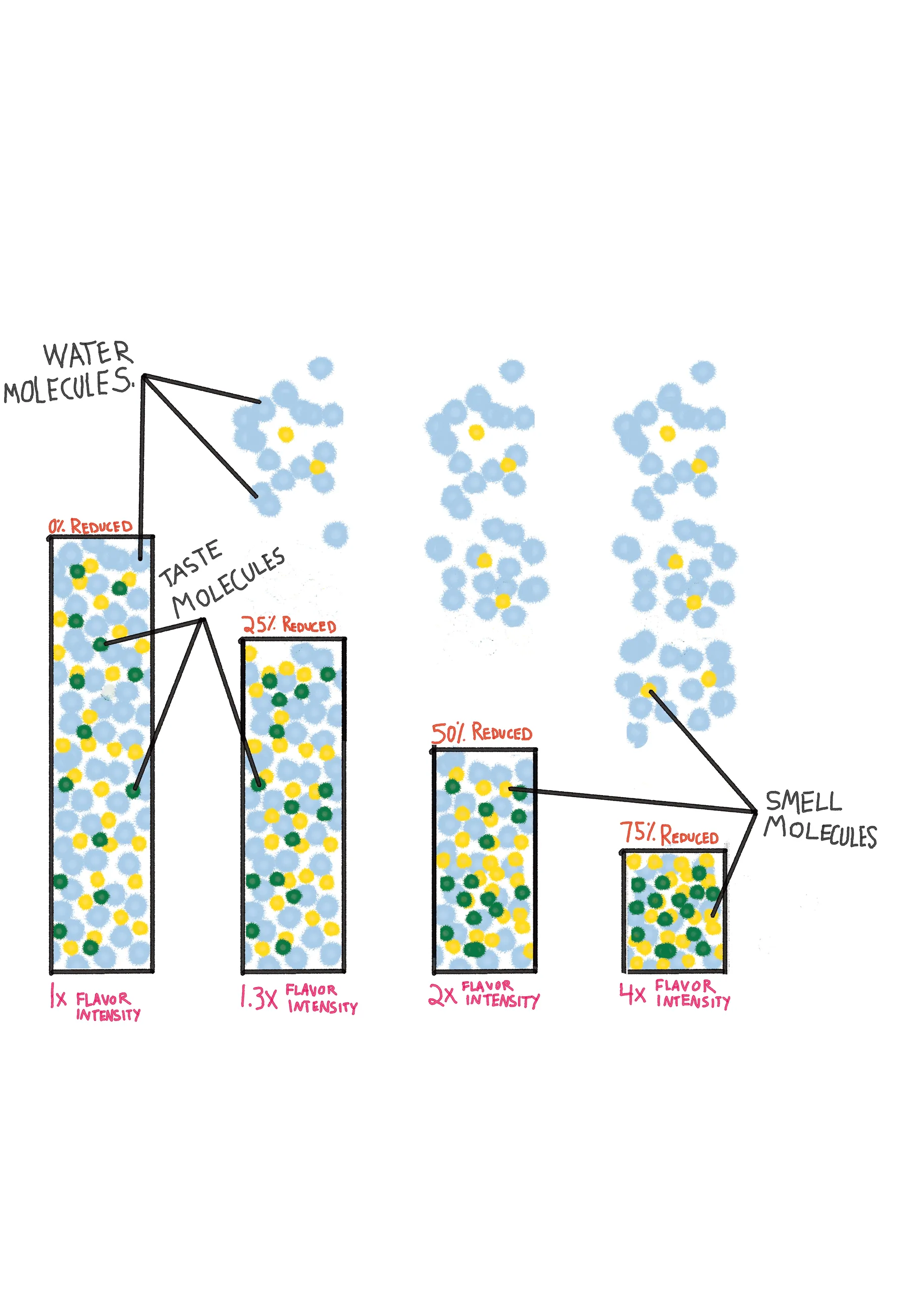

When you heat up smell molecules, since those molecules are volatile, they are able to basically spend time as a gas and float through the air. Once you heat them up, they will start to essentially boil off and dissipate. This is how a reed diffuser or one of those candle rings that you put essential oils into works. You heat up small molecules and they'll go up into the air more. They won't all do it at the same rate and to the same degree.

When you cook apples, or heat up pieces of fruit but specifically apples, you'll tend to boil off some of the lighter, tutti fruity and green top notes. What you're left with are a lot of what a perfumer might call the base notes, the physically and chemically heavier smell molecules that, in the case of apples, have this really decadent, plush, rose petal, cooked fruit, caramel, tobacco character. That's one of my favorite flavors.

My favorite apple molecule is called beta-Damascenone. It is a norisoprenoid. It's one of these apple base notes.

Do you have any advice on how to enhance the flavor of an apple pie?

Yes. One is to enhance the flavor of the apples themselves by trying to induce chemical reactions that will create more flavors than the apples already have. So if you were to roast or caramelize the apples a little bit, or if not all of the apples, some of the apples beforehand, you'll be introducing more flavor molecules into the pie, literally. If you include any fats or butter in the cream, in the filling itself, let the apples and the spices mingle together with any fat for maybe a day in the fridge before you put them all together and you'll get a much more permeated, infused flavor expression of all of those things.

If you wanted to go crazy, you could enhance the apple flavor of the apple filling by using a bit of apple molasses, which is really just reduced apple juice or apple cider. If you juice some of the apples and simmer [the juice] very gently until you make a syrup, you'll get a super concentrated essence of apple that you can then really beef up the apple pie with.

As water reduces, flavor gets a boost, giving apple pie a concentrated taste when the fruit bakes. Illustration by Arielle Johnson.

That's what I do.

Great minds think alike, I guess.

There are a couple apple farms that make an exceptional cider extract — boiled cider. It's so delicious.

I think that's a great example of how thinking about the science of flavor doesn't have to feel like an organic chemistry class. It can be a little enhancement to your existing culinary intuition. I'm glad you already figured that one out.

If you can exhort us to take on board one technique at home to create more flavor, what would it be?

I think one of the easiest ways to embrace this is to embrace the Maillard reaction. The Maillard reaction is a reaction between amino acids to the building blocks of proteins and sugars. Chemistry aside, it is the source of all of the browned, toasted, roasted flavors in things like chocolate, coffee, roasted meat, chicken skin, toast, brown butter. It's a reaction that has many different faces. Chocolate doesn't taste the same as coffee although they're both sort of brown-tasting.

The easiest way to use this to add extra layers of flavor to whatever you're cooking is to heat up any ingredients that you have, whether that's butter or a piece of meat, so that these things have a chance to react with each other and to, as much as possible, do things like dab the outside of meat before you sear it so that there isn't as much water. [That way], the water doesn't absorb all of the heat, the heat can go into the meat and then create this delicious browning reaction. A lot of the precursors, the building blocks for this stuff, are just hanging out in the ingredients that we're using all of the time. All you have to do is be a little bit clever about how you're applying heat to them and you'll reap all of these flavor rewards.

"Flavorama: A Guide to Unlocking the Art and Science of Flavor" explores the building blocks of yumminess. Photo courtesy of Harvest.