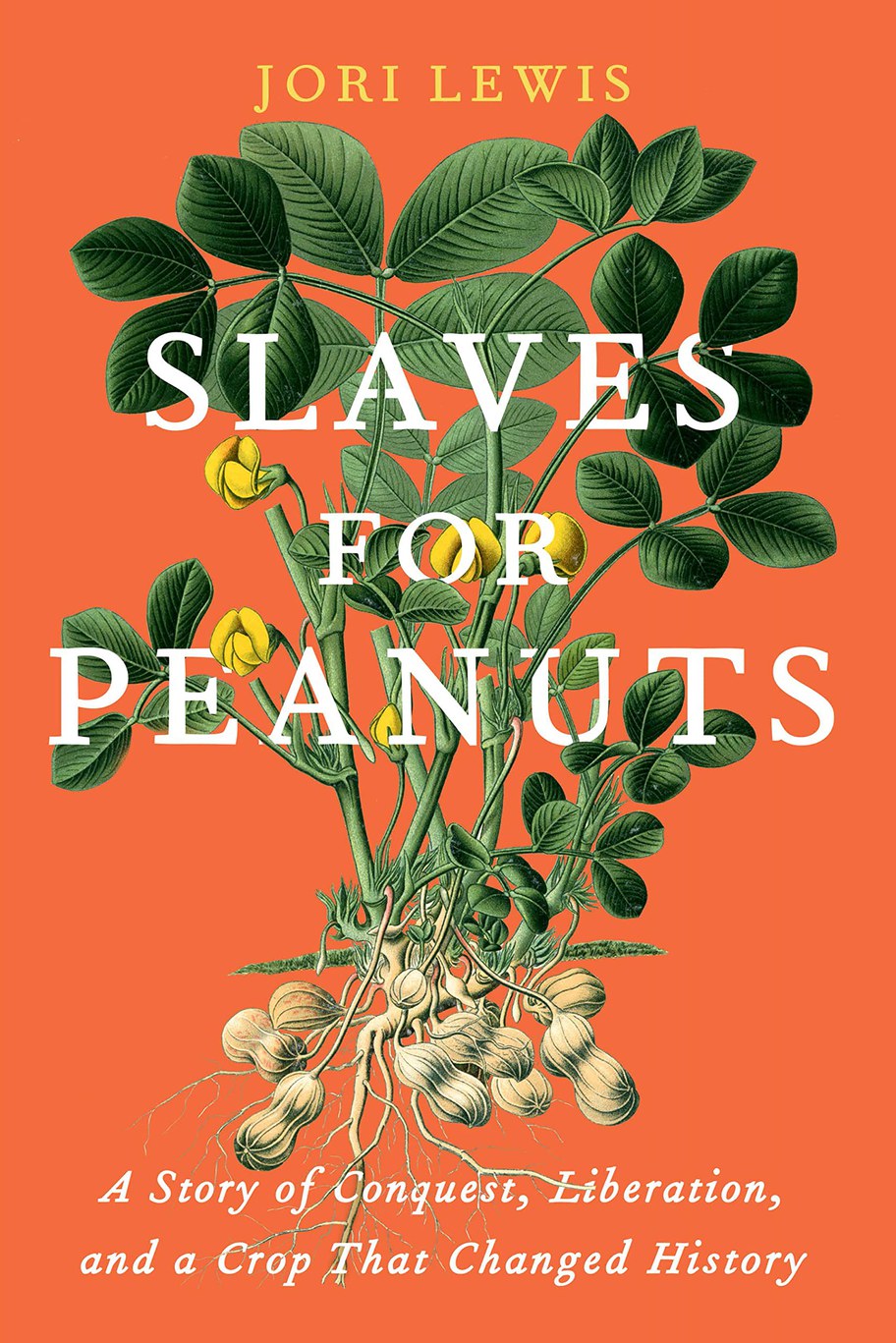

The sandy soil of West Africa was primed to farm peanuts. As the popularity of the legume increased, so did the need for labor. In the book “Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History,” journalist Jori Lewis dives into how peanut cultivation in Senegal supported the rise and fall of slavery.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KCRW: Does your family have a personal experience with farming peanuts?

Jori Lewis: It turns out it was my great-great grandfather who farmed peanuts on their farm in Arkansas. But then they stopped.

This book centers on Senegal. Why did you choose to tell that story from a place that is relatively small?

I have been living [mostly] in Senegal for the past decade. Despite its small size, some say the size of South Dakota, it has managed for over 100 years to be a top 10 peanut grower in the world. I was interested in the outsized impact that the peanut has on Senegal's economy, or had on Senegal's economy traditionally, and also its outsized impact in the world, being a small country producing so many peanuts.

Environment and agriculture journalist Jori Lewis comes from a family of former peanut farmers in Arkansas. She lives part time in Senegal, where the legume is an important export. Photo by Elise Fitte-Duval.

Where did the peanut originate?

Peanuts originated in South America and they evolved in a part of Bolivia. Then [peanuts] moved throughout the continent. There have been reports of peanuts in Incan graves, in the Caribbean, and the Brazilian coast. The peanuts would have spread far and wide – all the way to Mexico. The peanuts would have spread through South America, Central America, and to the Caribbean.

Do we know how and when the peanut made it to Africa?

The leading assumption is that it was brought over by early conquistadores and so-called explorers. I talk about in the book that on Columbus' first voyage, he talks about all these agricultural crops he’s eyeing to possibly take back to Europe, or to other places where Europeans, especially from the Iberian Peninsula, already had trade relationships. Africa must have been one of those places. The Portuguese especially had already established pretty good trading relationships in the 15th century, before the so-called discovery of the New World.

You ask the question, “How do we tell stories of people that history forgets and the present avoids?” How did you approach your research to determine what you call, “lost stories?”

I approached it with just dogged research. I'd been doing historical research, and especially with something so far away in time, where you don't really have any living descendants of that period, you have to rely on the archival materials. I just tried to triage all the materials that I could find.

Between the actual archival administrative materials, court documents, and register lists, I got a lot of the names of the enslaved from a regular publication in the colony’s newspaper that listed the people who had been freed in the past month. And there are fables, oral history, and missionary archives. I have a different perspective – [the materials] are kind of propaganda. At the same time, their mission is to uplift certain voices.

In some cases, I did try to do some oral history [research] – trying to understand how people pass on the stories about their lives, even if the details aren't exactly accurate. It's the feeling of the story that matters.

Who was Walter Samuel Taylor, and how did you land on him to use as a throughline to tell the history of the peanut in Senegal?

I stumbled upon a reference to Walter Taylor in another book – that there had been a Sierra Leonean Protestant missionary in the capital of colonial Senegal. It's unusual for a number of reasons. The Senegal was then, and still is now, a wild majority Muslim – it's between 90% or 95% Muslim. I always like to say the north of Senegal was Islam a thousand years ago. So Islam is old in the region. Also, it's a French colony. Catholicism had been the religion of the colony for many years.

Walter Taylor was a man of liberated-African origin, which means liberated Africans were a class of people who were resettled from slave ships and resettled in Sierra Leone, in the hills around Freetown. These were people who had been enslaved, had been put on slave ships, and then the British Royal Navy intercepted them and brought them to Freetown. They didn't take them back to their own countries, because in a way, it was a difficult proposition to do.

Taylor’s parents were liberated-African. Walter Taylor himself was born just outside of Freetown. Eventually he came to the region of Senegal, he says, to work for the British Navy. Then, he starts working for Boston shipmaster, who's exporting peanuts from the West Coast of Africa to the United States – to Boston, New Haven, and New York. From there, Walter Taylor has some kind of religious awakening and joins the French Protestant Mission as an evangelist and eventually creates the signature program of French Protestant Mission, which is a refuge for runaway slaves.

“Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Cropy That Changes History” highlights how how peanut cultivation in Senegal supported the rise and fall of slavery. Photo courtesy of The New Press.

Can you talk about how the growth of peanut farming and how the peanut industry supported the slave trade in Africa?

It's not a direct relationship. The demand for the peanut grew in Europe in the mid 19th century for a lot of reasons – mostly for making soap, but also for other reasons related to the industrial revolution in general, and there’s a large demand for oil.

From their colonial outpost, which are on small islands and peninsulas on the coast, the French asked the people in the interior of the continent to grow more peanuts. The French merchants are kind of like peanut boosters, but there's not enough labor to put more land into production. In order to put more land into production, people need bodies to grow peanuts.

Slavery always existed in Africa. The trans-Atlantic slave trade expanded and accelerated a kind of enslavement in the process by which free people were made enslaved – namely by war. Just because of the slave trade itself ended, it didn't stop the processes that were already happening. There are still a number of captives of war who have been enslaved – these people are still being created in the interior. And they find a willing market in the peanut lands of Senegal, parts of Guinea, and Gambia, at this time when trade is having an uptick.

When did peanut oil replace the slave trade as a “legitimate commodity?” And how does urbanization in the Industrial Revolution factor into that scenario?

“Legitimate commerce” is a term that many abolitionists were using as they're trying to outlaw the trade. They say that instead of trading in slaves, there are any number of other items they might trade within the so-called “legitimate commerce.” Peanuts are one of many things that are proposed as a legitimate trade – there's coffee, ivory, honey, hides for leather, palm oil, and peanut oil. There's a run on oil in Europe for greasing the new machines of the Industrial Revolution, but also for lamps for cooking, and especially in France for soap. The peanut has a chemical makeup that's very close to olive oil in some ways, and it was used in the recipe for the classic French soap, savon de Marseille. That's why there’s an uptick in demand for peanuts.