Margarita Carrillo Arronte has spent the last three decades cooking, studying and teaching traditional Mexican food. Born and raised in Mexico, she's owned multiple restaurants from Don Emiliano in Baja to La Colina in Tokyo. In 2010, she was part of the group that helped get Mexican cuisine added to UNESCO's list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Her 2014 work, “Mexico: The Cookbook” was such a hit. She's back with a new project, “The Mexican Vegetarian Cookbook.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KCRW: Where did your passion for cooking start? And how did you develop it?

Margarita Carrillo Arronte: My passion for cooking started at home. I come from a very traditional Mexican family, foodie-oriented. Since I could reach the stove, my mother allowed me to help her. My grandmother was very much into food. Every summer, she gave cooking classes to all her granddaughters, 11 of us. She taught us that through food through cooking something nice, it's a way to demonstrate love to your family.

You're often described as being an expert in “traditional Mexican food” What is traditional Mexican food by your own definition? And how does it compare to what you feel most Americans think of as Mexican food?

Real, traditional Mexican food is the food we have been cooking and eating for a very long time, for centuries. And cooking with the local ingredients: moles, sauces made with peanuts, almonds, nogada with nuts. Our food is sophisticated and delicate in many regions.

Since she could reach the stove, chef Margarita Carrillo Arronte huddled next to the other ten granddaughters, taking lessons in the kitchen from her grandmother. Photo by Ignacio ‘Nacho’ Urquiza.

What kinds of recipes did you decide to focus on for “The Mexican Vegetarian Cookbook?”

The further back you go into Mexican history, the more vegetarian the food. In Oaxaca, for example, we have a lot of vegetarian food made with herbs. In Michoacán, we cook a lot with pumpkin seeds. We have a series of energizing pastes made mainly with pumpkin seeds, and some of them with chelas seeds, and herbs like spearmint cilantro – it's like an energetic paste. Men take to the countryside to work, and at lunchtime they just heat up the tortillas and spread this paste on the tortillas, and that's what they eat in order to have energy until they come back home and have dinner.

The book is organized into various chapters for around meals. For breakfast, you have a recipe for something called huevos ahogados, or “drowned eggs.” It's very similar in a way to the Middle Eastern dish, shakshuka. Could you talk about the Mexican origin of these huevos and what the tricks are to making it?

You have to have fresh eggs so they won't break too soon. And you make a sauce, either green or red, and cook in a cazuela. When the sauce is ready, when the boiling flavors are correct, you lower the fire and break the eggs in the sauce. Then, add a little bit of fresh cheese at the end. Leave them to cook the white part of the egg. The yolks have to be fresh, and then serve them in a soup bowl.

Could you describe what the green sauce is made from?

It's a tomatillo, onion, garlic, cilantro, green chili serrano or fresh jalapeno. You dry roast them on a comal and then blend them into a sauce. Boil them, and when they're boiling, break the eggs separately, carefully. You have to serve it in a soup bowl.

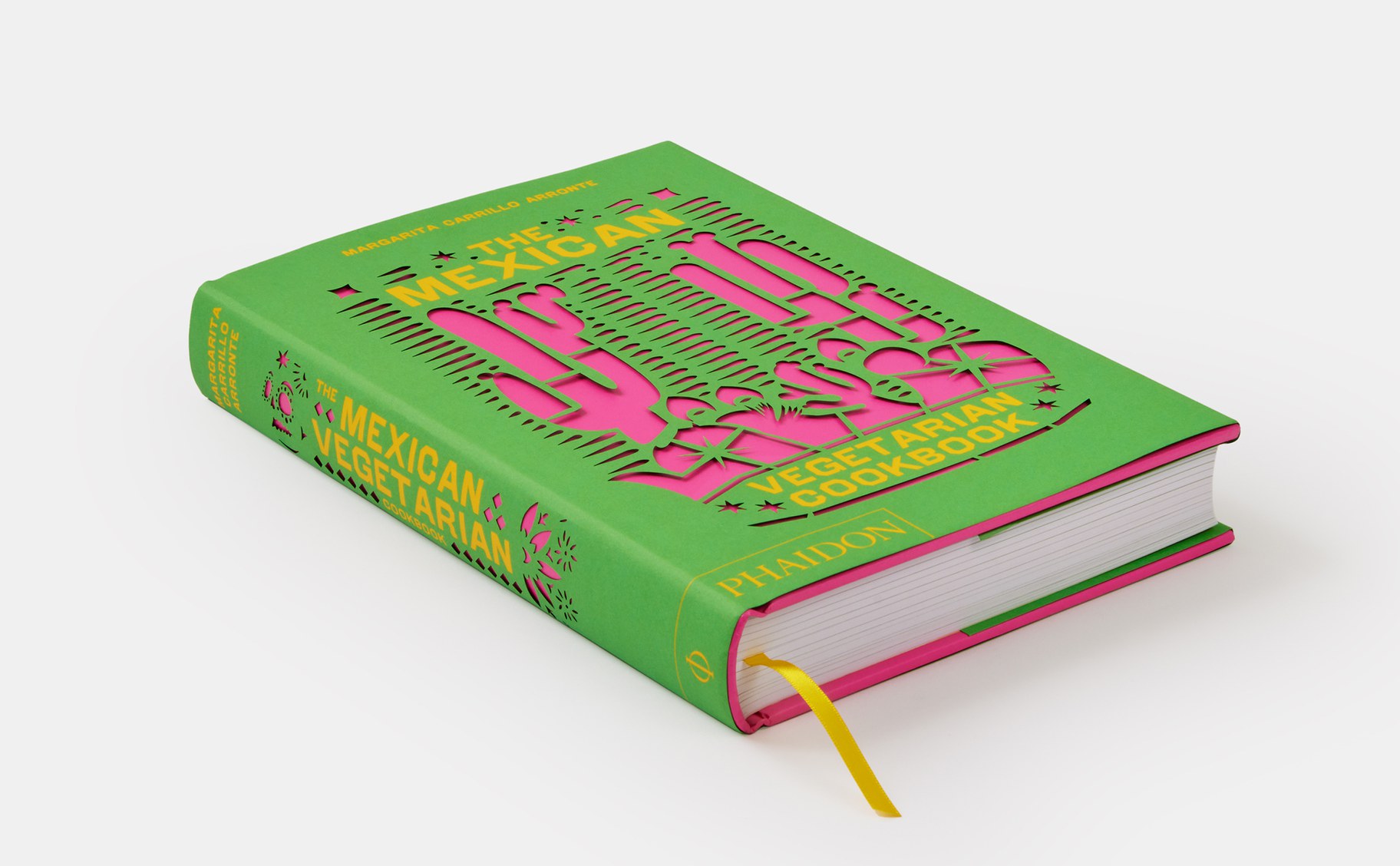

“The Mexican Vegetarian Cookbook” is organized by meals throughout the day. Photo courtesy of Phaidon.

Tell us about your huaraches – a dish that relies on masa harina.

Huaraches is one of my favorite dishes because you have to make a little golf-ball sized ball with your fingers. You shape it like a little glass, and you can stuff it with roasted pumpkin seeds mixed with dried chilies, and then close it. Then, you cook the huaraches in the black bean broth. And when they're cooked, they float up to the surface. Serve them in a soup bowl. I like to serve them wild edible herbs. The huaraches in the black bean broth makes it like a soup – thicker than soup. I add a little bit of cheese or a little bit of cream on top. In Yucatan, they make it with fish.

So they’re kind of like stuffed dumplings.

Yes, but with masa. They're delicious, especially with wild greens around it. You make a nest and inside the nest, you put the huaraches standing up, and add the boiling bean broth, and they're delicious.

I’d love to talk to you about huitlacoche. You have a crepe recipe that looks delicious. In the US, a lot of people may not have had or cooked with huitlacoche. What do they need to know about using this ingredient?

Huitlacoche is an accident from nature. When corn is growing, they are looking up to the sun. It rains a lot in Mexico, especially in central Mexico where huitlacoche is very common, and in the rainy season, the water gets into the leaves of the corn husks, and into the core. With the humidity from the sun, it becomes like the fungus of a mushroom. It’s been a delicacy since the Aztecs, and we use it for crabs, for soups, even for bread, like cinnamon rolls. When you add the huitlacoche, they're delicious.

For dinner, what would be a really stunning vegetarian centerpiece dish?

I would go for crepes of zucchini flour with goat cheese and mushrooms. And then you make a sauce of poblano and you help it with a little bit of cream. If you want to make them individually, you take each crepe and cover them completely with a huitlacoche with poblano sauce, and then add cheese on top of it, a little bit of cream and put them in the oven. And they're delicious.

HuItlacoche Crêpes

Ingredients

- 1 large poblano chile, dry-roasted and peeled

- 1 tablespoon butter, plus extra for greasing

- 15–18 Savory Crepes

- 3 cups (2. lb/1 kg) cooked huitlacoche

- 3 oz. /100 g fresh cheese, crumbled

For the sauce

- 1 tablespoon butter

- 1 cup (9 fl oz/250 ml) sour cream

- ⅔ cup (3. oz/100 g) cooked corn kernels

- pinch of ground nutmeg

- sea salt and black pepper

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 350F (180C/Gas Mark 4).

- Melt the butter for the sauce in a saucepan over low heat.

- Add the sour cream and whisk continuously until hot, then add the poblano chile and season with ground nutmeg, and salt and pepper to taste. Blend all the ingredients until you get a smooth sauce. Add the corn kernels and set aside.

- Fill the crepes with the huitlacoche and roll them up. Pour the sauce into a large, buttered ovenproof dish (or several smaller ones) and arrange the crepes over the sauce. Cover the dish with foil and bake for 10–15 minutes.

- Garnish with crumbled cheese, then serve immediately.

Basic Sweet Crêpes

Ingredients

- 1 cup (4. oz/130 g) all-purpose (plain) flour

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 cup (9 fl oz/250 ml) milk

- 2 tablespoons soda water

- 3 large eggs

- 3 tablespoons (2 oz/50 g) butter, melted, plus extra for frying

Instructions

- Sift the flour into a large bowl and add the sugar and salt.

- Add the milk and soda water, and whisk to combine. Add the eggs and keep whisking until smooth, then add the melted butter and whisk until combined and smooth. Let it rest for 1–2 hours.

- Heat a little butter in a non-stick frying pan, crepe pan or skillet over medium heat, add a small ladleful of the batter and swirl the pan to cover the base. Cook for 20 seconds, flip the crepe and cook for a further 20 seconds, then remove from the pan. Repeat with the remaining batter.

- Fill the crepes with sweet ingredients of your choice— fruit, chocolate, ice cream, creme patisserie, whipped cream, toasted nuts, hazelnut cream, etc.

- For savory crepes, omit the sugar, and fill with zucchini (courgette) flowers, huitlacoche, mushrooms, cheese, etc.

Chef’s tip: The crepes can be stored in the freezer for up to 2 months, stacked one on top of the other, with waxed paper between them, inside a well-sealed plastic food bag.