Of the many ways to learn about culinary history, using a quilt to tell the story of the African American food and drink producers foundational to American cuisine is particularly powerful.

Harlem Needle Arts is an arts and cultural organization at the forefront of revolutionizing, preserving, and expanding the narrative of fiber textile design and needle arts in the African diaspora. They took the lead on creating the Legacy Quilt, a narrative work pieced together from period fabrics, now on exhibit as part of the Museum of Food and Drink’s exhibit “African/American: Making the Nation’s Table” in New York City.

The massive quilt, which measures 14 feet tall and nearly 30 feet wide, includes 466 quilt blocks. Each quilt block stands for an icon in the history of agriculture, commerce, and invention who represents the African/American experience in food and culinary arts, dating from 1619 onward.

“The concept was to honor the first enslaved Africans who were documented to have been brought to the United States to Jamestown, Virginia,” says Harlem Needle Arts Executive Director Michelle Bishop. “So it was initially to start to commemorate that particular anniversary, if you want to call it [that].”

Bishop joins us to discuss the project’s inceptions and the stories and legacy woven into its fabric.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KCRW: Who commissioned the project, and how did Harlem Needle Arts get involved?

Michelle Bishop: We were initially commissioned by the Museum of Food and Drink. The vision of the project was from the lead curator Dr. Jessica B. Harris, who conceived the entire concept of the exhibition [and] that this part of the story should be told in quilt. They have sort of an advisory board who selected who should be involved and featured in the quilt. And then one of the administrators, Catherine Piccoli, reached out to us in July or August of 2019. And it had a few evolutions at the point when we came in.

How many quilters worked on the piece?

The core quilters were Laura Gadson and Sylvia Hernandez, and then Ife Felix helped occasionally.

As the chef-owner of Dooky Chase’s in New Orleans, Louisiana, Chase turned a sandwich shop into an upscale restaurant for Creole cuisine, immortalizing dishes like her gumbo z’herbes. Over seven decades, diners included leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, celebrities, and U.S. presidents. Photo courtesy of Museum of Food and Drink.

Can you elaborate on the period-appropriate fabrics used in the design?

Starting from 1619 forward, the sashing that's around each quilt block or the backing of the appliquéd icon that's featured on the block had to be appropriate to that time period in history. And of that time period, let's say it's 1600, 1700, African Americans were not allowed to wear the same fabrics as the people who were enslaving them. Basically, they were left to wear things that were like a burlap, crocker, [or] muslin kind of fabric. And then as time progressed, ginghams, flannels, so on and so forth.

What was the process of the research that went into determining how large the quilt would be and who got placement on it?

The size of the quill, they basically told us how they wanted it to be. We worked out the math and then gave them the actual definitive size.

Who vetted the icons that made it onto the blocks?

Dr. Jessica Harris … Catherine [Piccoli], Peter [J. Kim] who was the Executive Director of MOFAD [at the time], they convened a board of advisors. So they did the research and selected who should be included in the quilt. It includes inventions, so you may see objects that are part of the quilt block, like the ice cream scoop. What you're looking at in those cases are the original designs from the patent for that particular object.

People from West Africa, where Oryza glaberrima (African red rice) is a native crop, established rice cultivation in the U.S. Lowcountry. These farmers and their descendants created complex agricultural systems including dams and field irrigation. Photo courtesy of Museum of Food and Drink.

Alexander P. Ashbourne and Alfred L. Cralle are represented on the quilt. How are their contributions depicted?

Mr. Cralle is the person with the ice cream scoop. There were about three iterations of the ice cream scoop. Initially, one was in a cone shape, and then one was circular. And then there's a woman who developed the piece in the ice cream scoop that actually allowed for the shift of the ice cream out of the scoop. So there are about three different people involved.

Mr. Ashbourne did the spring-loaded biscuit cutter, and he received the patent for it on November 30, 1875. In some cases, there were people who were enslaved or worked in environments where they said, “We can do this differently. How can we create an apparatus to make our lives easier?” So a lot of this came out of a necessity that they saw.

Can you describe a couple blocks that have special resonance for you?

There is a block which features two women sitting down with shopping bags in front of them. And they are part of the category considered the Movement. In 1969, the Black Panther Party was the first to institute or enact the free food programs in schools, or in their schools. And out of that movement, later — I believe it was in the 1970s — the United States government put into place a meal program within the school system. So that actually came out of the Black Panther movement.

The other is Shirley Sherrod, who worked with the Department of Agriculture, who had helped many farmers across this country gain access to funding, materials, things of that nature. She's an advocate for farmers, and is still working with farmers across the country. [And] Reginald Lewis. In the ‘80s, Reginald Lewis was the person who purchased Beatrice Foods. At that time in history, he was with us, all that he had done, not only with the business of food, but for the community at large. So those are some that ring out to me.

Historian Dr. Jessica B. Harris was lead curator of the exhibit “African/American: Making the Nation’s Table,” on view at the Museum of Food and Drink through Juneteenth. Photo by Angie Mosier.

Can you talk about the art form of the quilt in the Black community and why you feel it was chosen as such a moving way to communicate?

The African American experience, and beyond, in quilting… the history, on one hand, it was very utilitarian. It was a means of staying warm. It was a means of saying, “Well, let's piece together what we have.” We deal with what's called three layer quilting. So there's a top, there's a middle, and there's a backing. So in times where they didn't have the modern amenities that we have right now, they would use newspaper to stuff quilts. They would use old clothing, anything that they could use to create a covering. And as times evolved, of course, you had gatherings of people making quilts. And not only women. There were men that were a part of the construction of making quilts to tell stories.

The story in the quilt is … you’re the griot, carrying on the message. As we carry on quilts from one generation, pass them on from one to the next, to the next, you continue to tell the story of what is happening in the quilt. If you're using old clothing, well, that may have belonged to someone who passed away.

So as we tell this historical story, there are 406 blocks, of which 400 of them have an icon. There are countless stories that haven't even been included. This formation of a quilt carries on generations of storytelling, generations of us being griots, generations of us exploring who we were in the cultural landscape of the country, and in this case, of course, of food.

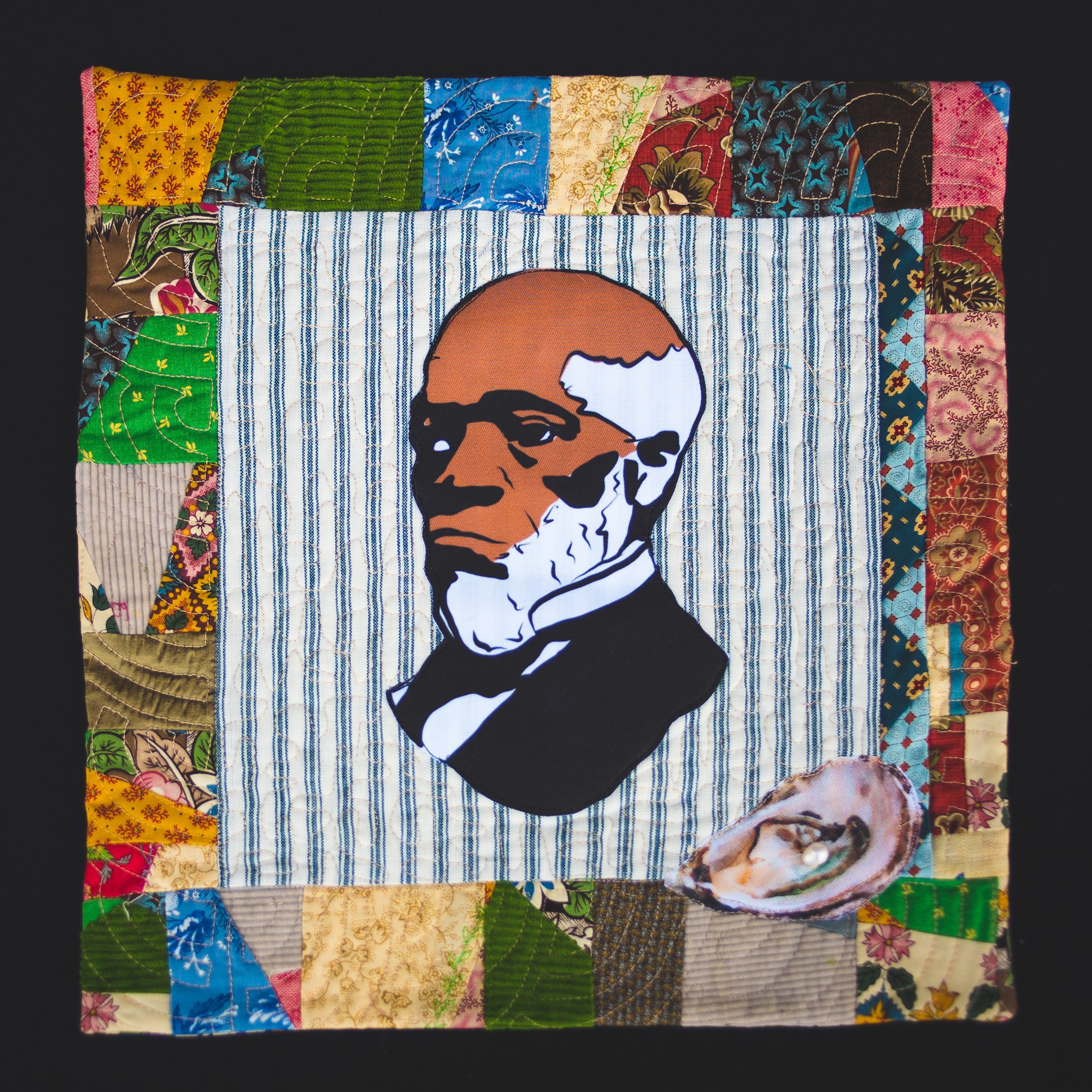

Raised on Virginia’s eastern shore by free, land-owning parents, Downing was known as the “Black Oyster King of New York.” His popular Broad Street oyster house catered to affluent diners and was world-renowned. The cellars of his restaurant were a stop on the Underground Railroad. Photo courtesy of Museum of Food and Drink.