On the road to self-discovery, there are many ways to parse and understand the tension between family ties and individuality. For Eric Kim, a writer for the New York Times who contributes to the Food section, New York Times Cooking, and the magazine, food has been at the center of this journey.

Kim returned to his hometown of Atlanta during the pandemic, where he worked on his first cookbook “Korean American” and unlocked the tricks to his mother’s kimchi.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KCRW: The first time you ran away from home, where did you go? And what did you begin to discover?

Eric Kim: I ran away to my cousin Jaime's house in Nashville. And she was there cooking on the line. She lived in this adorable house with a tiny, tiny stove. I remember it so clearly, it was white and very small, narrow, and she had a Dutch oven. And so I got to cook in a Dutch oven for the first time. And I remember making coq au vin and just feeling so exhilarated at this idea that we were cooking as adults. I was only 17 at the time. But I realized that's really where this book started. Because it was so important to me in discovering the Korean part of my journey and the American parts as well.

How did you discover that you could use food to play with the space between your Koreanness and Americanness to achieve a personal harmony?

I think it took maybe two years of not just writing the book, but also editing it. And it was a very painful but joyful process. I always talk about this book as a thing that really changed my family's life. When you get to see your story on the page made into a story that narrates the past, the way things actually happen aren't that neat. And it takes the referring back to organize it into a story that makes sense. And that's a really healing process.

It really started for me when I started writing about food. I wrote an essay about coming out to my mom, and she made us kimchi fried rice. That was this nexus point, and it kind of anchored the piece. And that was my first time trying memoir. I felt after that first essay about kimchi fried rice [that] I wasn't able to get it all out of my system yet. So this book was sort of my way of vomiting all over the page.

While interviewing his mother about food for his cookbook, Eric Kim describes tapping into her memories that she had forgotten. “I learned so much about my mother as a person, [it’s] one of the biggest journeys I’ve had,” he says. Photo by Jenny Huang.

You moved back home to Atlanta from New York to cook with your mom for this book. And you've named a chapter in your book “The Tiger in the Hand.” Can you speak about the experience of absorbing lessons, not all of them culinary?

I always describe my mom as a tiger. She's a tiger zodiac. She is a feisty person. She's kind of the voice of our family, very much a pack leader. I think I was able to tell these stories about the kitchen because of the food that she was teaching me about. It was through the conversations I had with my mom sitting across from her at the kitchen island. She would cook in this way that was so open.

She taught me that in order to cook well, you have to be in the mood for it. I realized that she would just cook throughout the day, as she had time and as she wanted to. And she would never cook when she didn't have to. That worked out because there was all this food in the fridge that she had made previously. And while sitting across from her in that kitchen, I heard stories she would tell me about when she was little in Korea, when she was a teenager, when she was in college — these stories that just never came out … for years.

What food does is it helps you tap into old memories. Not just any memories, but memories that you had forgotten you even had. And so I learned so much about my mother as a person, and that was one of the biggest journeys of this book, and one reason why I really recommend people to stand by their parents and watch them cook and learn a recipe and interview them.

One of my favorite things about that chapter was how you managed to capture the language that she used to transmit what to look for in a dish.

One really important thing that I had to get across was the cultural nuances of this cuisine. There's this word called “sohnmat,” [which] translates to hand taste. It's just the perfect way to explain this kind of cooking. And this kind of cooking exists across all cultures, but especially in Korean food, where you're kind of using your hands to balance the taste and the flavors. You're not really using measuring cups or spoons.

I think there's a lot of experience in the hands that is really hard to translate. And that was my job as a recipe developer, to try to approximate at least that flavor, which is mom taste, mom food, and the way she seasons her food — everything from that to the little bottles of syrups and vinegars that she reaches for. And it took a lot of just watching her cook in an everyday kind of way for me to recognize that there's some magic here.

Can you speak a bit about the role of sweetness in Korean food?

Sweetness is really important in Korean cuisine, and it's usually to do two things: balance all the salty, spicy flavors, and create this [word] which means sweet, salty. And that flavor is just so tongue-latchingly good. I think there was a point in my mom’s life where she just stopped using sugar for that, because sugar would normally be in these soy sauce braises and these sweetened gochujang chicken dishes, but she reaches for a maesil cheong, which is a green plum syrup.

At first I was trying to get her to stop using that because I wanted the recipes to be accessible. But as I wrote this book, I realized how political it actually all was to decide which ingredients to use in a pantry. What I realized was, accessible to whom? So what I wanted to show is that if this amazing green plum syrup, which has such a fruity nuance, is so important to her cooking, then it has to be in the book.

Tell us about a dish that is uniquely Southern and uniquely you, the gochugaru shrimp and roasted seaweed grits.

It was one of the first recipes I developed when I moved back home, and my mom kept asking for it. What I loved about that dish was that it wasn't just shrimp and grits with Korean influences. Each part of it is a reference to another Korean thing. The shrimp are marinated in lots of garlic, fish sauce, and gochugaru, which is this amazing Korean red pepper powder.

Those are the flavorings used for a fish stew called maeun-tang. And then the grits are flavored in the way that I love my juk — rice porridge, other cultures call it congee. It's that sesame oil, that gosohan, that nuttiness that's really hard to replicate. I like to crush in a whole packet of roasted seaweed snack, gim. Gim is just the flavor of my family. I realized while cooking that, wow, gim is something that we put in everything. And it makes sense. It has so much umami.

Tell us about your mother’s kimchi fridge.

My mom has about two or three kimchi fridges. She has a fridge in the basement and another fridge in the garage. The second fridge, for a lot of people, is a place to create a pantry of your own, and my mom's “pantry” involves all kinds of kimchi. The book only covers her napa cabbage kimchi, and she has a lot of radish kimchis, burdock root kimchi, and mustard green kimchi that’s really incredible. A lot of these more nuanced, bitter kimchis that just make my mouth water because they are so wonderful.

Which dish most represents you right now?

I'm in this weird nostalgia beat. The dish that really means a lot to me in terms of that is the maple milk bread. That milk bread sort of stops time for me, because it takes so long for the bread to proof. I like that, because you have decided to spend this time on that milk bread. I really encourage people to make it, because there isn't more of a Korean American story, in my mind. It's a replication of the loaves that we would find on Buford Highway. And this woman named Seong Hee Kim started this chain of Korean bakeries in Atlanta called White Windmill. Whenever I make that bread, I'm taken back to Atlanta, taken back to the past. There's a lot of stories in the past. But they become real resonances once you tie them to the present, and that's what I'm doing right now with my work.

Gochugaru Shrimp and Roasted-Seaweed Grits

Serves 2

If shrimp and grits were born and raised in the American South by Korean immigrant parents in the early 1990s, then this is what it would taste like. In my version of the Southern classic, the shrimp is first tossed in gochugaru, fish sauce, and so much garlic (these ingredients, my mom reminds me, are the start of most recipes for maeuntang, a spicy fish stew, like the one on page 169). The grits are, on the other hand, flavored in the way that a classic Korean jook, or rice porridge, would be flavored: with crushed gim and toasted sesame oil. And when the two combine, it’s a beautiful marriage of seaside flavors.

Ingredients

- 1 cup whole milk

- ½ cup quick-cooking grits (not instant)

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

- 1 tablespoon unsalted butter

- 2 (5-gram) packets gim, crushed with your hands

- 2 teaspoons toasted sesame oil for the shrimp

- 4 large garlic cloves, finely grated

- 1 tablespoon gochugaru

- ½ teaspoon celery seed

- 1 tablespoon toasted sesame oil

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

- ½ pound jumbo shrimp, peeled and deveined

- 2 tablespoons unsalted butter

- 2 teaspoons fish sauce

- 1 teaspoon fresh lemon juice

- Pinch of sugar

- Fresh cilantro leaves plus tender stems, for garnish

Instructions

- Cook the grits: In a medium pot, combine 1¼ cups water, the milk, and grits and season with salt and pepper. Bring to a simmer over high heat, then reduce the heat to low. Whisk occasionally and cook until soft and tender, about 10 minutes. The grits should be thick but still loose, meaning they’ll coat the back of a spoon and very slowly drip off. (If they’re too tight and don’t drip in this way, then just add a little more milk.) Add the butter, gim, and sesame oil and stir to combine. Adjust the seasoning with salt and pepper as needed. Keep warm while you prepare the shrimp.

- Cook the shrimp: In a medium bowl, whisk together the garlic, gochugaru, celery seed, sesame oil, and salt and pepper to taste. Add the shrimp and toss to coat.

- Set a large skillet over high heat. Melt 1 tablespoon of the butter in the pan. When the butter is hot and the foam begins to subside, add the shrimp in a single layer. Let them cook until lightly browned and no longer opaque (you should see them start to pink up where they hit the pan), 1½ to 2 minutes. Use tongs to turn them over and cook the second side until similarly blushed, about 1 minute more. Remove from the heat and add the fish sauce, lemon juice, sugar, and remaining 1 tablespoon butter. Set over low heat and toss together until the butter has melted and coats the shrimp in a shiny orangered sauce, and the shrimp are cooked through, 1 to 2 minutes.

- To serve, spoon the grits onto a large platter or into individual bowls, then top with the saucy shrimp. Garnish liberally with the cilantro.

Reprinted from Korean American. Copyright © 2022 Eric Kim. Photographs copyright © 2022 Jenny Huang. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Random House.

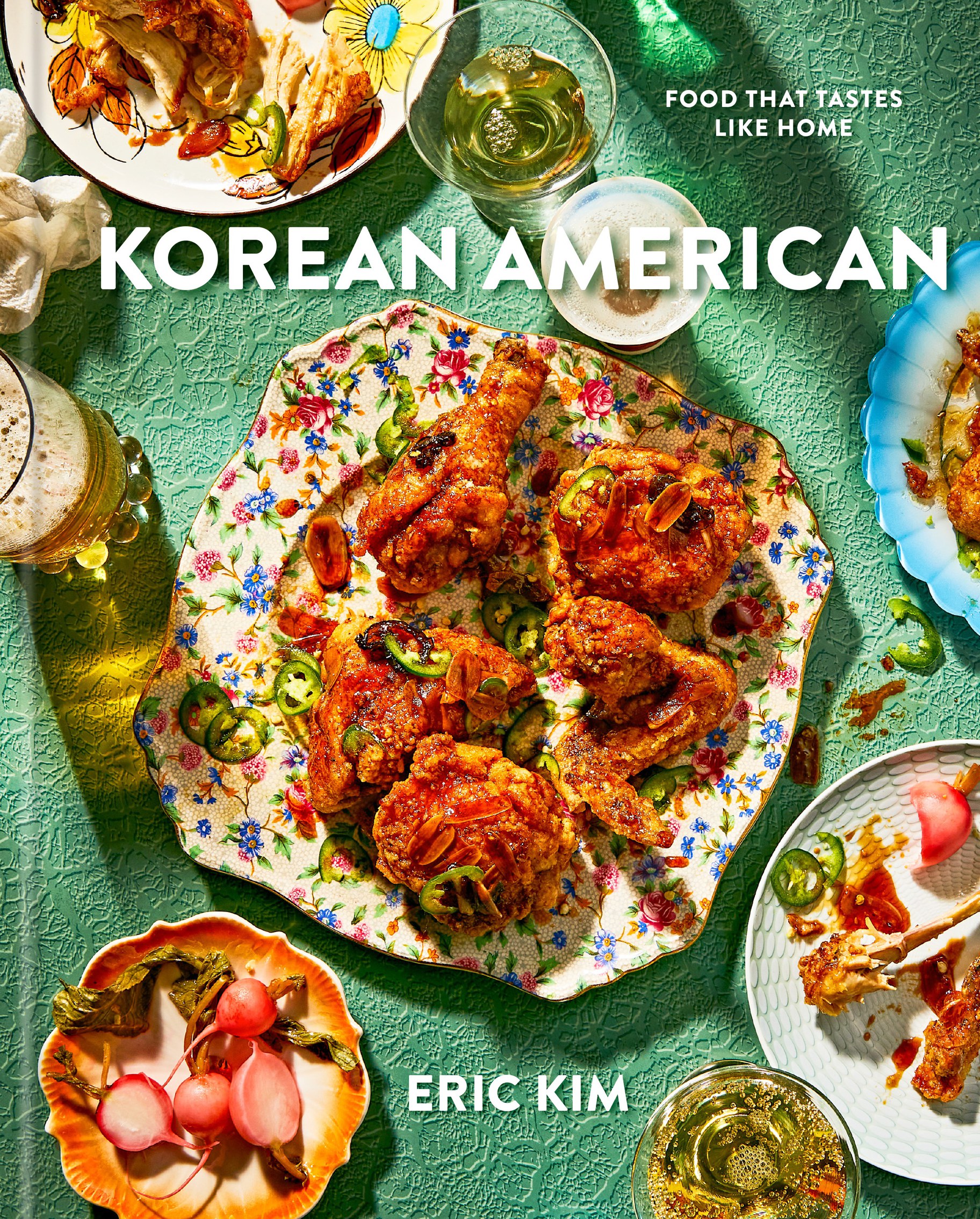

Eric Kim’s “Korean American” is his first cookbook with a dash of memoir, as he balances his heritage growing up in the South. Photo courtesy of Clarkson Potter.