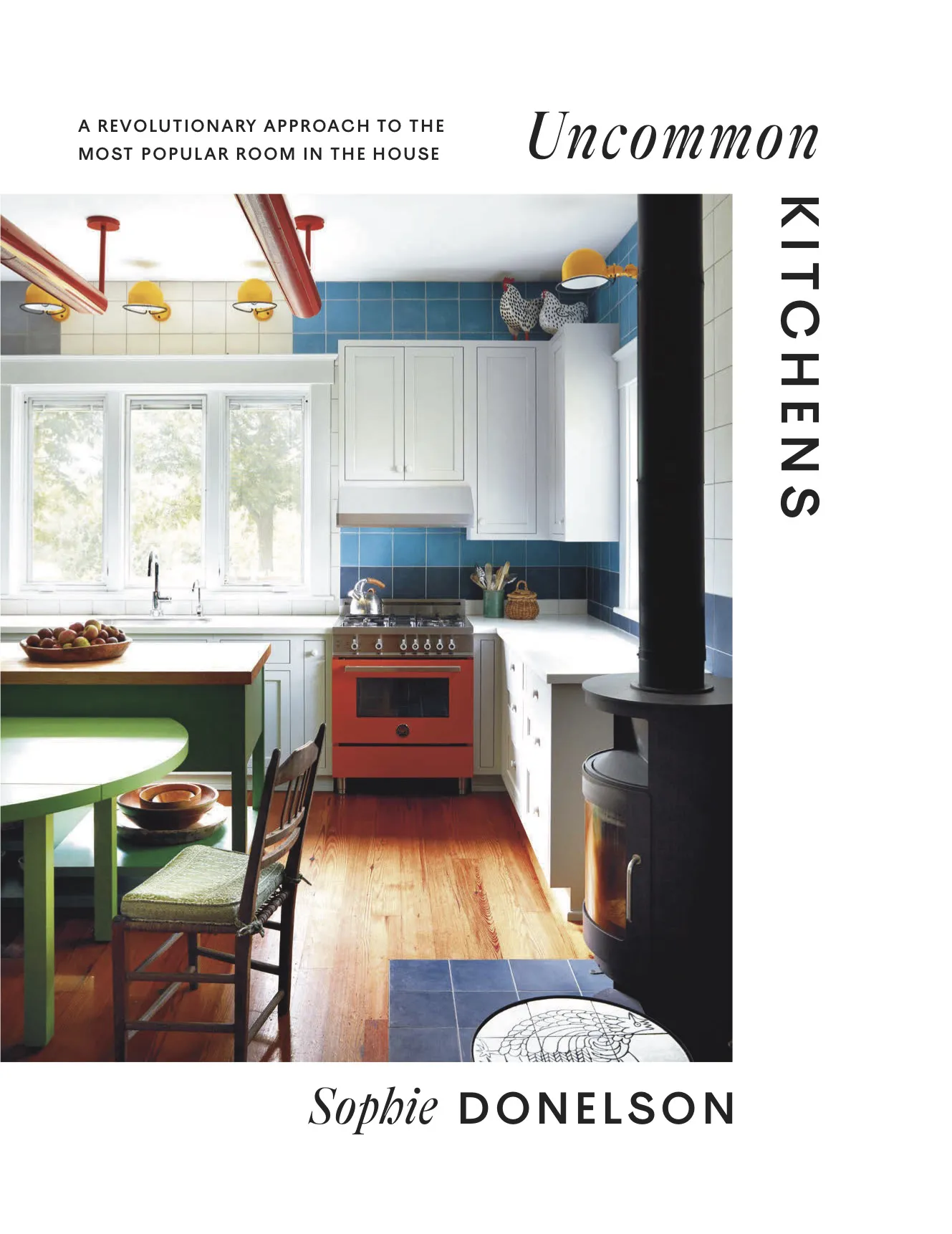

Kitchen renovation… it can be a massive undertaking, requiring homeowners to make big decisions with long-term ramifications. And the design industry is geared toward a certain look, what Sophie Donelson calls a PWK — a "Perfect White Kitchen." A design journalist and the former editor-in-chief of House Beautiful, her new book is Uncommon Kitchens, which offers a fresh approach to the most popular room in the house.

KCRW: You say that we have reached "peak kitchen." The internet is awash in kitchen porn. Why did you feel compelled to write this book?

Sophie Donelson: Because I didn't like what I was seeing. I think we have been taught by media sources, TV, Instagram and now Tik Tok, you know how to make what I see as a "PWK," a Perfect White Kitchen. I wanted to know what else there was. It feels like the media has a certain job of representation, and we get called to the mat when we're doing it poorly. And I think that design media has been doing it poorly with kitchens. There are some exceptions but I felt like I was seeing a lot of the same things and the evolution of a certain aesthetic. I really wanted a whole book, something you could hold in your hands and a brand that said, there's more to the kitchen than this.

I've had this bifurcated experience of kitchens. In my professional job, all the years I was a chef and catering in Southern California, I've seen hundreds of $150,000 kitchens that were absolutely pristine but bloodless and soulless, places that I think people rarely cook or gather in. When I think about my favorite kitchens, they are the kitchens that I saw in the 1970s, '80s and '90s in Italy, the kitchens of nonnas. There's a humaneness to them, a place for people. When did we get away from that?

It has to do with the housing crisis and 2007 was a real inflection point. Decisions were being made, I call it fear-based decorating, that we would start designing our kitchens with resale in mind. This is around when people in America realized that their entire nest egg was in their home, and that their way of accruing wealth in the world was totally tied up with their home. Therefore, the choices that they were making inside their house felt necessary and right and imperative to be dictated by the market gaze, about the value out there or what other people think is worth spending money on.

That shifted everything. And despite the market changing many times since then, we haven't really come back from what I would say is that "fear-based decorating" where you could go this color or that color or this tile or that tile, but to be safe, we're gonna go with blah. No one's ever like, "Oh my, god. I found the most amazing grayish tile and I can't wait to install it." It's like, "Well, I love lavender and I wear it every day and I live in it and it's my favorite color for 30 years but I went with taupe. It's the kitchen and I didn't want to make a mistake." Just hearing people talk about that is depressing. So, there are alternatives and the book is rife with them.

The walk-in pantry in author and designer Sophie Donelson's kitchen in Montréal is adorned with salvaged shelves from the 1950s and a splash of color. Photo by Patrick Biller.

For me, a lot of it is the monolithic nature of cabinetry.

Yeah, I call it the unitard or the bodysuit of design. When did everything have to be connected? [When did it happen that] the below cabinets had to be the same color as the above ones? And they had to be seamlessly paired together with stone or a composite? And then everything was just sort of uniform and in a row?

I use the word "unkitchen" to describe these unfitted kitchens but all kitchens were at one time unfitted, much like yours is still now, which is to say that there was a table and then later a counter. There was a hoosier cabinet that held pantry items and cutlery and china. There was a hearth that was standalone. You would add tables, chairs, and a drying rack above the hearth for clothing and a comfy chair because back in the day, mostly women would spend a ton of time there. So you'd find a comfy place for you to be.

These kitchens were rooms that were pieced together for the needs that they had. One way of looking at modern kitchens is saying, "What of those pieces do I need? What's necessary there? Is it possible to leave a little wiggle room or flexibility when I design it?

That was one thing you spoke about often in the book, the idea that things don't have to be 100% finished. One needs to leave room open for change, which is, of course, what life is all about.

I think that is a golden rule. People say, "You wrote a book about kitchens." I'm like, "No, I didn't. I wrote a book about life." A lot of the lessons in there are what I've honed from 20+ years of writing about design and interviewing incredibly bright designers and architects and homeowners and renters about how they live and what works for them and what doesn't. One thing that the brightest people that I talked to come back to is sort of this idea of getting to 85% and then recognizing that maybe there is a little bit of wiggle room.

Color leaves a big impact on this small kitchen in South London. Photo by Michael Paul.

There was a point in kitchen design, and we might still be there, where it just felt like every new kitchen came with an island. Can you please dispel us of this notion? Can't we just use a table instead?

We can and we probably should. Now there are islands that have legs. They are referred to by the Brits as work tables, which is a nice hybrid. One thing that's nice about a conventional table is that it's been doing a really great job for thousands of years. It seats and suits a lot of people. Barstools are good for a certain age bracket that I think is somewhere between 18 and 46. It doesn't work for a lot of other people. So I'm a big fan of the kitchen table. It works great on all sorts of things, and it's quite convivial.

To me, the ultimate conviviality in a kitchen is a UK kitchen diner, where you have the sink, the refrigerator, the stove. Everything is there but there's also the table, the chairs, and maybe even a comfy chair or a sofa.

Yeah, the Brits have it right, as usual when it comes to home design. These British kitchens are one of the things that inspired this book. I was seeing that PWK, Perfect White Kitchen, trending on Instagram. Then [I was seeing] this British unkitchen with maybe a curtain below the sink instead of cabinet doors and a kitchen table and pots and pans exposed and knives out and signs of life. The same people were liking both images, right? It was like, "Ooh, I want a perfect kitchen, I want it to look like that." Then they would have this emotional, visceral reaction to these cottage kitchens. It touches somewhere in our soul that is personal to each of us but it's also universal.

Soapstone, unlacquered brass, and copper give this remodeled 1940s kitchen in Sacramento, CA some age. Photo by Shavonda Gardner.

The book is full of delicious kitchens, some of which are highly designed and cost ungodly amounts of money, and some which are labors of love. Those are definitely my favorites. But you map out a handful of ways that design can improve our kitchen experience, whether we're renovating or renting. Let's start with one of the most inexpensive ways to provide a facelift: color.

If you have walls to paint, for sure. But there are so many ways, if you have a white or a gray kitchen, or a rental that's in a weirder taupe color leftover from the '80s or '90s, which is the accessories that you choose and also decorative items. So tea towels and towels and exposing them and having that is a sweet thing to do. So is hanging a piece of art. I find that if you can't directly address the idea of painting your cabinets, which is a great option, too, if you're up for it, or making some other kind of big changes, and if you're not up for a rug on the kitchen floor, which I personally, really like. It's not so hard to get a rag rug. They go right in the washing machine. You can put them out and sweep them and they're just fine and not scummy. But hanging a piece of art is something that people don't really think about because they think that the kitchen goes by sort of a separate set of design rules and mores. The truth is that most things that live in the other parts of your home are totally at home in the kitchen.

One thing that I find really interesting is every time I see pictures of cabinetry that are broken up into different colors, I think "Oh, that's beautiful." That's a way for it not to be monolithic. But buying colored cabinets is so pricey. You suggest that people buy white cabinets and paint them.

That is definitely something you can do. There's a great British kitchen in the book that does that. But cabinet fronts are getting more accessible. Semihandmade is one of the many companies that does fronts, specifically for IKEA cabinets. You can buy the IKEA boxes and then the fronts from these guys and get a colorful thing. Also, they can be painted. I'm not going to advocate everybody do a DIY [project]. If you're not already inclined to do that, I'm not going to proselytize you to do that. But there are professionals. An old trick from interior designers is to bring it to an auto body shop. It involves getting the doors off the boxes and getting them beautifully enameled the way you would a car.

The kitchen is divided into a cooking area and a cleanup area in this home in LA's Fryman Canyon. Photo by Jess Isaac.

You've been writing about design and kitchens for a while. When it came time to do your own renovation, was it easy for you to make decisions or was it more difficult?

It was horrible.

That makes me feel so much better.

It was horrible and I did a terrible job. I wrote the book at the same time. It was a big year of learning and working. Lo and behold, I'm a much better writer than I am a kitchen designer. I'm not living in a house that's in the book anymore. But I renovated what was a great 1950s kitchen that I would have kept as-is except for the electrical, which was dangerous. So it was time to upgrade. And I went all in.

A lot of us have these hopes and dreams about renovations. I lived in New York for 19 years before having the chance to live in a house and to do a house kitchen. I had a lot in my mind about it. As I was doing it, what I was finding was that the manufacturers and the designers and the whole world of design is out there to get you to have this picture perfect, common kitchen, even if you choose a cool color. I was really bristling at being funneled into this place where it felt like I couldn't break free.

Everybody around me was talking about practicality and functionality and the kids and making lunches. And I was like, "Yeah, but wait. There's got to be more. There's got to be other ways to do this." Life takes twists and turns, and we don't own that house anymore. I live on my own with my two boys in a really funky rental with a really lackluster kitchen, and I'm super happy because I feel free. I feel freed from a big expensive kitchen. I have the ability to make these little incremental changes and live out what I've been proselytizing in this book and in other writing. It's a really joyful kitchen. It has a great pair of windows and we do a lot of work in there, a lot of fun projects and a lot of cooking. To me a messy kitchen, an imperfect kitchen, a kitchen that's being used is a kitchen in which love is happening all around.

Uncommon Kitchens is rife with ideas that extend beyond taupe tiles and a blah color palette. Photo courtesy of Abrams.