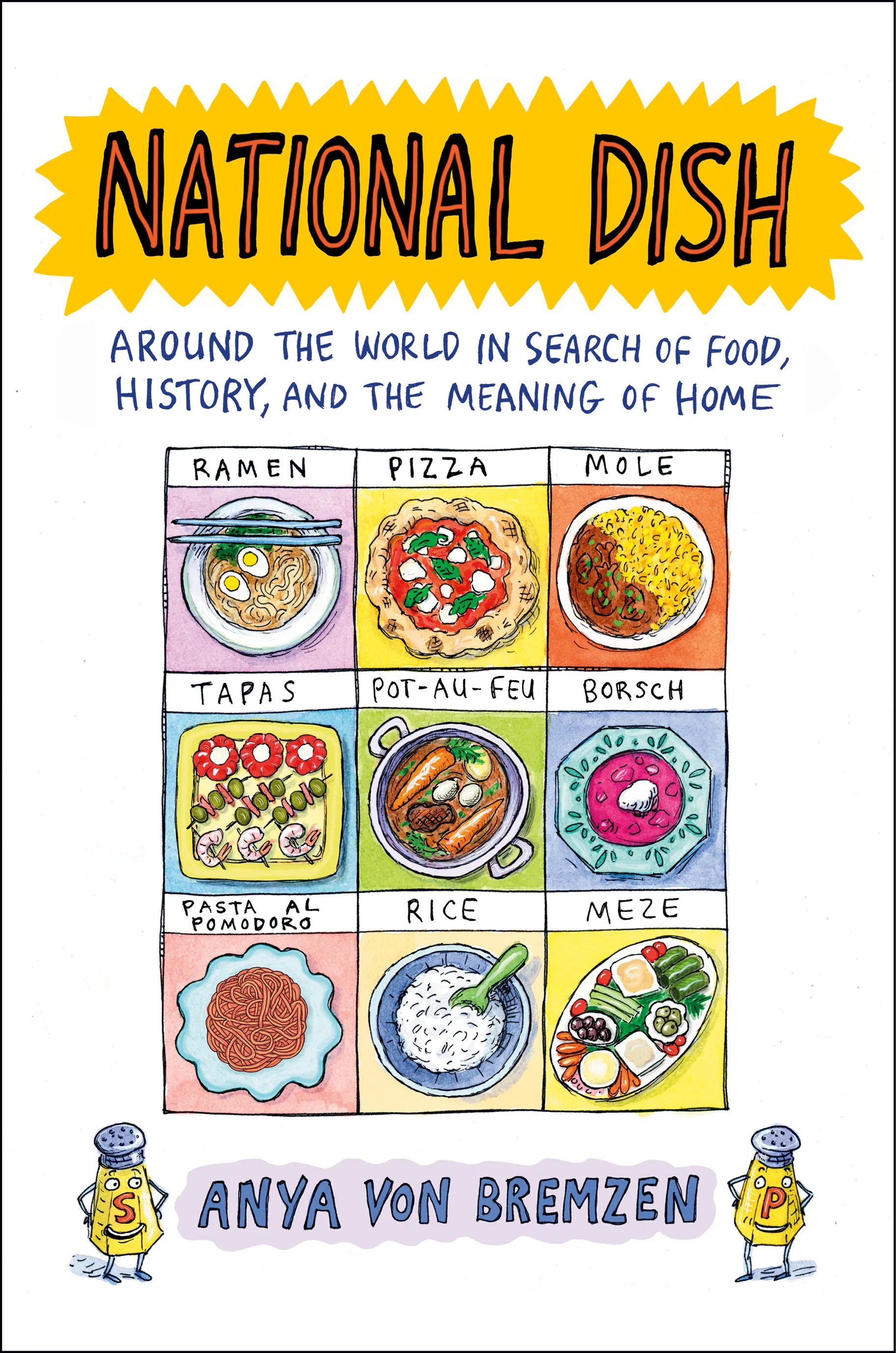

We've talked to Anya Von Bremzen before, whether we're getting tips on how to tailgate like a Russian, flashing back to her first American Thanksgiving, or exploring her culinary memoir, Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking. This time, instead of excavating her identity through food, Anya explores culinary and cultural identities in various countries around the world. For her latest book, National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home, she dove into the foods of Paris, Naples, Tokyo, Seville, Oaxaca, and Istanbul.

KCRW: I find the question that's embedded in the subtitle of the book so intriguing and increasingly difficult to answer. You traveled "around the world in search of food, history and the meaning of home." Did you find it, the meaning of home? Because I find that in a world with ever-increasing migration, this idea is ever more elusive.

Anya von Bremzen: Absolutely. Actually, at the end of the book, as I was finishing, the war broke out. My former home country attacked Ukraine and, in a sense, I lost a home. The last chapter, the epilogue, is about borscht, which Russians think of as their own dish but is, in fact, a Ukrainian dish. It was connected for me with the idea of home but I felt like I could no longer own it, because it didn't really belong to us. So for me, this journey was complicated but, in a sense, I was looking for other people's ideas of home. I went to all these different cities and looked at the idea of national cuisines to see how other people connect their idea of a dish to home, to place, to their national identity.

Let's start with Paris, the beginning of your book. What neighborhood did you choose to stay in while you were there? And did you come to Paris on that particular trip as a lover or a skeptic?

I've always had a very complicated relationship to Paris. I'm not the kind of person that has these swoony, rosy memories of oysters and terrine. I've spent a lot of time in Paris and I always found it very difficult and overbearing, precisely because the mythology, the national idea of Paris as the capital of this greatest nation on earth, at least gastronomically. It always oppressed me.

But we ended up staying in a neighborhood that was very similar to the one I live in, Jackson Heights, in New York. In Paris, it was the 13th [arrondissement], which is completely multicultural. So from day one, I eased into this globalized idea of immigrant Paris. That went a long way to lifting my fears and anxieties about it.

"I thought I could no longer own it, " says Anya von Bremzen as she reconsiders borscht, a Ukrainian dish that conjures feelings of home in her native Russia. Photo by Derya Turgut.

The dish that you chose to focus on in Paris was pot-au-feu, a dish which is really interesting from a historical point of view. One thing I find really fascinating about this book is how history and politics are contrapuntal but really important in the way that we eat food in the present. All this stuff lingers.

Absolutely. Everything about food is political — where it grows, the land belongs to someone, who grows it, who sells that labor. In this book, I chose to focus on one political issue, which is the issue of national identity. We assume that countries existed as long as language existed and that our connections to places are primordial and that dishes were eaten centuries ago. But that's not true at all. In fact, it was France and the French Revolution and the constitution in the name of equal citizen[ship] and a unified language that really influenced the way other nations formed themselves. So France was a crucial place to start.

Pot-au-feu is an interesting example of a national dish because it was always described as such. It was constructed in a way. The great 19th century French chef, [Marie-Antoine] Carême, who I devote some ink to in the book, called it a truly national dish. Following his example, it was something that was taught to young ladies in culinary schools. It was a way of nationalizing women to serve this nourishing meal. It's got this mythical element because it's a pot on the fire. It's soup, meat and vegetables, all in one pot.

As I found out, one pot dishes are always used for their symbolic weight. It's the idea that it can feed the whole country, it can feed the rich and the poor, so it was a great symbolic dish to focus on. But what I discovered in France is that hardly anyone cared. I started interviewing people and they said, "Oh, yes, grandmother's pot-au-feu, how nice. Let me tell you about this new Mezcal bar. Oh, there's this great bao bun place. There's a chocolate babka that you can find in Paris now." This was the reality of a globalized city that almost gave up on this national heritage, on the personal level, not officially because it's always touted as the greatest gastronomic nation on earth but I found that the city had moved on.

More: Anya von Bremzen on how to tailgate like a Russian

In your book, you talk about the idea of liquid modernity. What does this mean? For so many of us, particularly those of us who live in cosmopolitan cities, where, to a great degree, there are no permanent bonds, how does it play out at the table?

It's very paradoxical. Liquid modernity was a term that was coined by a Polish philosopher, Zygmunt Bauman, to talk about our postmodern condition of not being a perpetual tourist everywhere, not having these attachments. That's how most of us live in the globalized world. But as the world becomes more liquid and more globalized, as a counterpoint to that, we develop this idea that we should have these attachments. In a way, the global and the local, they feed each other. They can't exist without each other. The more globalized we get, the more we will want to belong. Don't you find that?

Absolutely. You feel adrift.

Yes, especially now with all these wars and displacement. Food is an incredible, powerful symbol of home, whether it's a real home or an imagined one. I've heard so many migrants' stories about going through this difficult journey and sitting down to a meal from the home country, something remembered and feeling the sense of comfort and relief. It's also a myth. Food unites us and brings us comfort but it also divides us.

More: Anya von Bremzen on her first American Thanksgiving

Talk a little bit about the contrasts of the different places where you were and how these ideas played out. You went to Japan, a society which despite individual chefs' intense embrace of foreign cuisines, where you can find better Italian food than in Italy, is still essentially insular. And then you have Istanbul with this expansive inclusion of so many diverse traditions.

After Paris, after almost giving up on the idea of a national dish and being happy in this post-national city, eating globalized food, I went to Naples, and I worked on pizza. Naples is a great example of a city that hasn't lost its connection to its food and its sense of identity. We have to remember, when we talk about Italian food, there was no Italy until the 1860s. There was no Italy until unification. Naples was the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and a completely separate place from the North. But as unification happened, it was folded into the Italian nation and a lot of Neapolitans are still unhappy about that. Pizza, to them, is a symbol of something that is Neapolitan as opposed to Italian.

Then I moved to Tokyo and as my national dish, I was researching a dialectical duo of ramen, which is a recent addition. It's a Chinese-originated dish that the Japanese made their own and turned into a kind of symbol of "cool Japan." I also researched gohan, the boiled rice that accompanies most Japanese meals and is imbued with this sense of ancient and great Japanese-ness. But here's the paradox. Even though it was promoted as a cornerstone of washoku, which is a traditional Japanese meal, and as something sacred, Japanese eaters are turning away from rice. Rice consumption is going down. A lot of the Japanese prefer to go to the depachika, [food markets in] department store basements, and get some imported side dishes. For many local preservationists, it's almost a losing battle.

We have this sense of Japan as being insular and proud of its traditions, which it is. But when you look at the numbers, they don't add up. Sake consumption is down, rice consumption is down. It's very interesting. And when you talk to the Japanese, the way that they internalize and appropriate important ideas is fascinating. Many Japanese people I talked to think McDonald's is Japanese. They call it "love dog" and they were very surprised.

That's amazing.

From Tokyo, I went to Seville, to look at the tapas tradition. I chose Seville because it's in Andalusia, which is this symbolic representation of Spain. All the cliches of Spain are from that region. It's also a very constructed ideal. In fact, tapas is also a fairly modern institution. This whole kind of shuffling from bar to bar, that was related to post-Franco La Movida, when people could go out. It was a symbol of a new lifestyle. So that was very interesting.

From there, I went to Oaxaca to work on tortillas and mole, mole being a traditional representation of Mexico's dual identity, which they call mestizaje, the mix of Spanish, colonial and indigenous influences. That story also develops because of colonial moles, and the whole idea of mestizaje is being critiqued as a very white ideology. So there's this whole movement to promote other moles, which have less Spanish elements, like the segueza. So that was extremely interesting as well.

National Dish explores the food of Paris, Naples, Tokyo, Seville, Oaxaca, and Istanbul to find the connection between place and identity. Photo courtesy of Penguin Press.

I want to talk to you about gastro nationalist food fights, and the idea of who owns a recipe. If we think about borders as being fabricated and languages as being more expansive, a recipe can have meaning for more than one set of people.

Absolutely. I think this whole idea of national cuisine is fairly recent and extremely constructed. Once you have incomes, nation branding, promotions, it has monetary value. Who owns hummus? Who owns baklava? Who can brand it as their national dish? It's not innocent. It's not just nationalism and national pride. We have countries spending millions of dollars promoting their national cuisines. That's when we get the fights.

When we come to the part of the book where you are in Istanbul, you happen upon the conceit of putting together a collection of dishes on one table, like a potluck, to represent this intense, multicultural culinary landscape. You talk to so many different friends and acquaintances in your quest to try to identify the dishes that should be part of this potluck. When you cooked with your Sephardic Jewish friend in Istanbul, you started to wonder if language was key to home and identity, and you asked if a coiled pie Turks know as gül (rose) börek would taste different if you called it bulemas de carne. I say yes. What do you say?

I say absolutely, yes. As a bilingual person who also speaks a lot of other languages... for instance, when I say shashlik, which is kebab in Russian, it conjures up one world. When I say kebab, it's something else altogether. That conversation with the Sephardic lady was extremely interesting because she did a documentary on Ladino, which is a disappearing language of Sephardic Jews. The Jews here in Turkey have spoken it since they were exiled from Spain in 1492. Imagine how much identity was preserved through that language and the names of the dishes. But now, in this globalized world, where right now there are not a lot of Jews left in Istanbul, it's disappearing. Cooking, they fear, is going along with it. I think, definitely, language is one way to preserve a whole culinary world.

I had the same conversation with the Zapotec activist Eufrosina Cruz Mendoza in Oaxaca, who is one of Mexico's most prominent indigenous politicians. She's doing a lot of programs to preserve indigenous languages. In Mexico, she told me exactly the same thing. She said a whole landscape, a whole way of thinking, a whole way of celebrating a fiesta will be lost if you lose the language.

More: Mastering the art of Soviet cooking with Anya von Bremzen

As you came away from finishing the book and ending with an epilogue on borscht, how did you end up feeling about the place for national dishes in a globalized world?

A lot of the things I discovered in the book had to do with mythologies and how recent some of these dishes and myths were and how constructed a lot of these stories were. But I came up with the realization that it actually doesn't matter. For instance, when the USSR collapsed and all these post-Soviet nations came into being, within 10 or 20 years, you saw whole cultures being born and nation-building and storytelling.

It doesn't really matter whether it's authentic. What is authentic? The whole idea is nonsense. It is authentic to the people who internalize it. This was my realization.

Even my mother said with the whole thing about borscht, it doesn't really matter whether it originated in Ukraine or present-day Russia because the categories were different. What's important is what these dishes mean to people at any given time and that can change, especially with social media and especially with national identities and identity shifting. What's important is what food represents and its power.