Home economics classes typically evoke thoughts of the bland and sterile — insipid foods, domestic pandering, and ill-fitting A-line skirts. But the women who pioneered home economics knew the subject could be far more than that. They believed that improving the home could, and would, improve society.

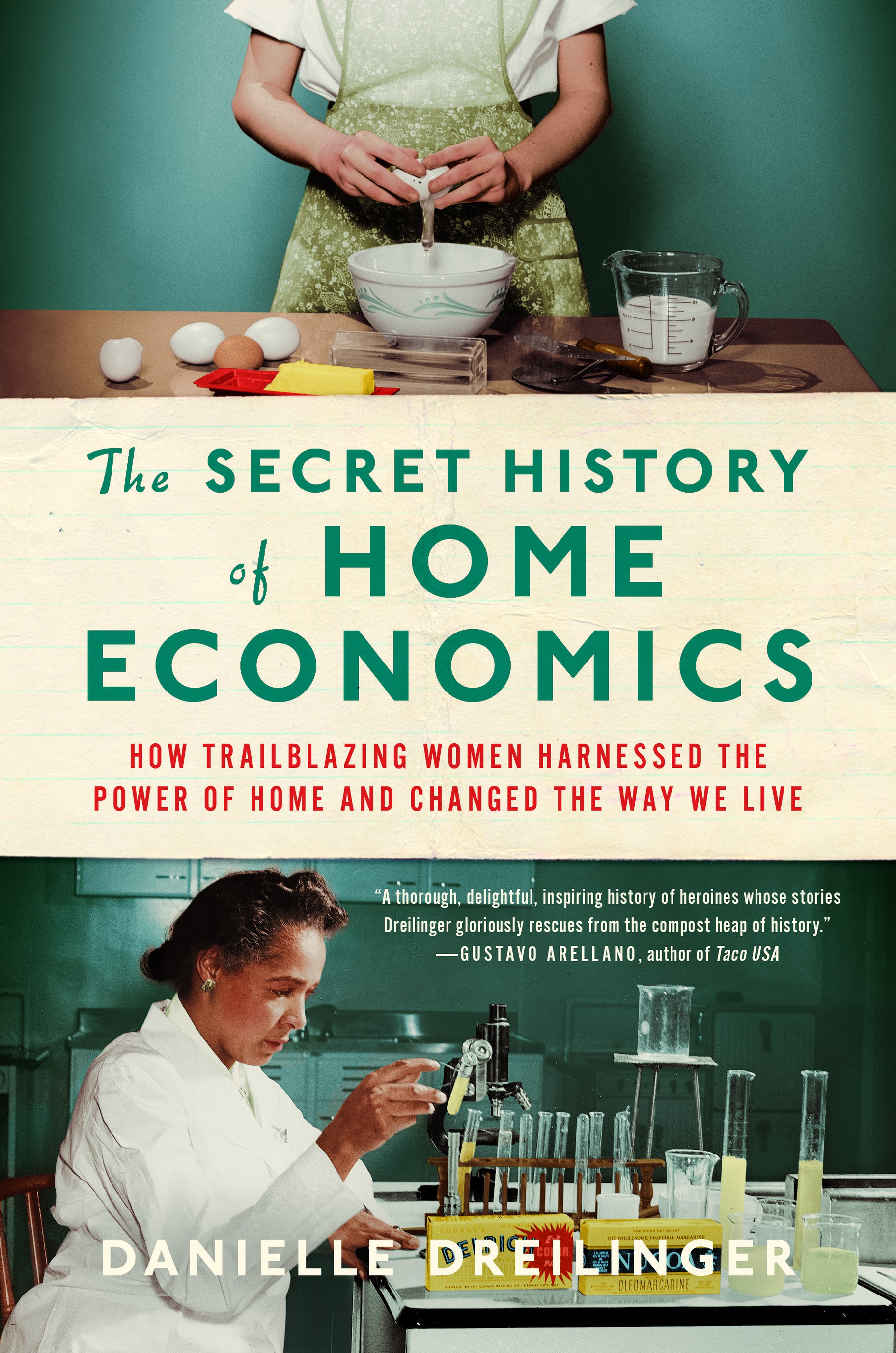

Was the backbone of home economics moral, scientific, or both? It's a question that journalist Danielle Dreilinger asks, as her research about the history of the subject veers far from the cooking and sewing you may remember in high school classrooms. Dreilinger discusses her work and her new book, “The Secret History of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed the Way We Live.”

KCRW: What was the state of education for men and women, Black and white, in the 1800s?

Danielle Dreilinger: “One thing that surprised me is that education was very limited, even for white people, in the middle of the 19th century. As we know, people who were enslaved could not be taught even how to read. But most people didn't spend much time in school at all. And it wasn't until well into the 20th century that most people graduated from high school. So the opportunities for schooling were really limited.

Part of what drove home economics was this explosion in education, both K-12 and college, after the Civil War that expanded this world of who was getting educated, from elite white men, to people of color, to women, to people interested in science, to farmers. And educators started asking, ‘What do all of these people need to know?’ And there became a group of mostly women arguing that home economics — this field that they created, the science of the home, and how science applies to the home — was an important piece of that puzzle.”

You say that when women married, it was as if they died legally.

“Yes, very depressing. Women couldn't sign contracts in their own name. Women couldn't receive wages. And they were supposed to be in the home. The first sort of proto-home economist, Catherine Beecher, tried to redefine the home as a place of power, as the most important part of our society, because it's where we raised the citizens of tomorrow. But the women who came 20, 30 years after her and founded the field of home economics have a really complicated view of the home … which is that they, on the one hand, wanted to bring science into the home, so that you could do the work efficiently and get out and do other things. Because the home was not interesting, the home was no longer economically productive.

But at the same time, they found power in women's lesser status and [in creating] a range of careers where women would be accepted and could create their own business world, because they were connected to the home. Women were seen as authorities in child rearing, so they could become teachers or preschool teachers. They were seen as authorities in cooking, so they could become caterers. They could run hotels because they ran homes. So it was a really fascinating project — instead of turning their back on the home altogether, to redefine it and expand it.”

“The opportunities for schooling were really limited,” says Danielle Dreilinger. Part of what drove home economics was an explosion of education in the 20th century. Photo by Kathleen Flynn.

So it wasn't that they were interested in “sending women back to the kitchen?”

“Absolutely not. A bunch of people have asked me like, ‘Oh, all these people have taken up sourdough bread baking, isn't that so home ec?’ And it's no. Home economists believed in takeout. They believed that you should test whether home baked breads with no commercial yeast or sourdough are better than what you could buy in the store. They believed in setting up pure food and drug laws so you could buy bread from the store and know that the flour hadn't been whitened with lead. And they believed in examining the value of the home bakers’ time. ... They had this really analytical and, at times, quite coldly objective view of the value of spending time in the kitchen.”

Who were the founders of the field?

“The first generation of women to go to college is who became these founders of home economics. Many of them were unmarried. Ellen Richards was the first woman to go to MIT, which did not take women at the time. But she managed to convince them to let her basically audit classes, though they did eventually give her a degree. And she was a chemist, she was a public health scientist who turned her interest to the science of the home.

You also have Margaret Murray Washington, who grew up in Mississippi right at the end of the Civil War. She was a Black woman who got a bachelor's degree, started running home economics at Tuskegee, where she married Booker T. Washington, and became an enormously influential advocate for improving the African American home and the political, moral, and economic value that had. They were running on parallel tracks due to the racism of the time. Ellen Swallow Richards drew a range of women around her who all really delved into creating curricula, legislation, and university programs that, for a long time, most of the women who taught in colleges taught in colleges of home economics.”

Born in Mississippi during the Civil War, Margaret Murray Washington went from washerwoman’s daughter to college dean and advanced ideas of domestic work in the Black household. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B2-3673-8.

What fields did home economic majors of the past go into? Was it kind of a backdoor to get women into the sciences?

“Oh, absolutely. It was a backdoor to get women into the sciences and also into business. It was really funny to look at it, because these women were not allowed in chemistry labs, for instance. But if you decided you wanted to study meat protein development, you could get a job in the home economics lab. When the Bureau of Home Economics opened in the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 1920s, it became the biggest employer of women scientists in the country.”

What does the field of home economics look like today? And what is it called?

“Home economics is still around. It is mostly known by the name ‘family and consumer sciences.’ The field rebranded in an effort to shake the associations that people have with home ec. It might sometimes be called ‘human ecology,’ ‘human development.’ You can still earn a degree in well over 100 colleges in the U.S. At last count — the stats are a little bit old — more than 3 million middle and high school students were taking home economics every year in the U.S. In other countries in the world where it's still required, all kids take it.

And those classes are really interesting because they're really tied into contemporary concerns. There is a fairly recent Family and Consumer Sciences Teacher of the Year who focused on anti-bullying. You have so much about personal finance and kids learning about how credit cards work, how student loans work, which is obviously a really important subject when you're in high school, and making those big decisions about your future.

But then you have some classes that are the ones that I would love to see even more of that take this big strength of the home economics movement, which is this combined macro and micro way of looking at the world. And they connect learning how to sew on a button with the life cycle of a cotton T-shirt. A teacher named Angela DeHart in Virginia did that. And so then students know not only how to sew on a button, but why it matters. Like why you can get a pair of pants for $10 at Walmart, what's the ecological and the human cost and the labor problems and so on behind those pants.

So I thought it can be a really innovative and fun course that also teaches career skills. You can get your ProStart certification, your ServSafe certification in high school cooking classes here. It's not just making muffins, it's how do you have a job in the catering industry? So it's still very much in that way part of the original vision of home ec.”

“The Secret History of Home Economics” traces the paths of the women who were chemists, marketers, and educators, in a field that has been both denigrated and embraced. Photo courtesy of W.W. Norton & Company.