"Throughout history, African American alcohol consumption has been portrayed as derelict," writes award-winning food journalist and historian Toni Tipton-Martin. She spent two decades buying and studying recipe collections for her award-winning book, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, and its follow-up, Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking. In her latest work, Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs, and Juice: A Cocktail Recipe Book, Tipton-Martin trains her focus on African American mixology, ensuring that those behind tradition and innovation are not forgotten.

Evan Kleiman: I love this book. It has so much exuberance.

Toni Tipton Martin: I had so much fun working on this book.

I'm sure. You can feel it. Can you share your early memories of your parents' hospitality and your father's makeshift bar?

My family was part of that generation where backyard barbecues and entertaining and picnics were classic summer activities. Plus, my parents were club members, so they often had friends over for parties. My mom used to love to set up this lavish buffet in our basement and my dad built himself a really cool bar. Initially, that bar was made from my grandmother's hideaway bed. It was very cool. I can just remember it. I was only about six years old but it had Asian etching on the outside of it. It basically looked like a box that had a fold-out twin bed inside. When you opened it, the top doors above the bed, which is a kind of peculiar combination when you think about it, was a bar. She kept her glassware in there and this amazing little Popeye decanter that I was in love with as a child. When they outgrew that (maybe it was falling apart, I'm not exactly sure), my dad built his own bar and began collecting different things from around the country when they would travel.

Can you talk about the mixed messaging that surrounds black people and booze?

It's been really interesting and I'm still able to see the pervasiveness of this today. For the longest time, perhaps since freedom, African Americans were portrayed in literature, in television and film, in every piece of pop culture, as people who the men were going to be dangerous and violent if they were caught drinking and the women who drank were loose and wild. Those kind of stereotypes percolate all throughout our history up to and including the years preceding Prohibition. It's not really widely known, or at least it wasn't known to me, that so much of the argument on behalf of temperance was about the danger of Black men. But many African Americans were, at the same time, trying to establish themselves as moderate, as learned, as reliable. All of the things that were being said about my ancestors, they were working diligently, many of them, to dispel those mythologies. So we have this fraught relationship with public alcohol consumption.

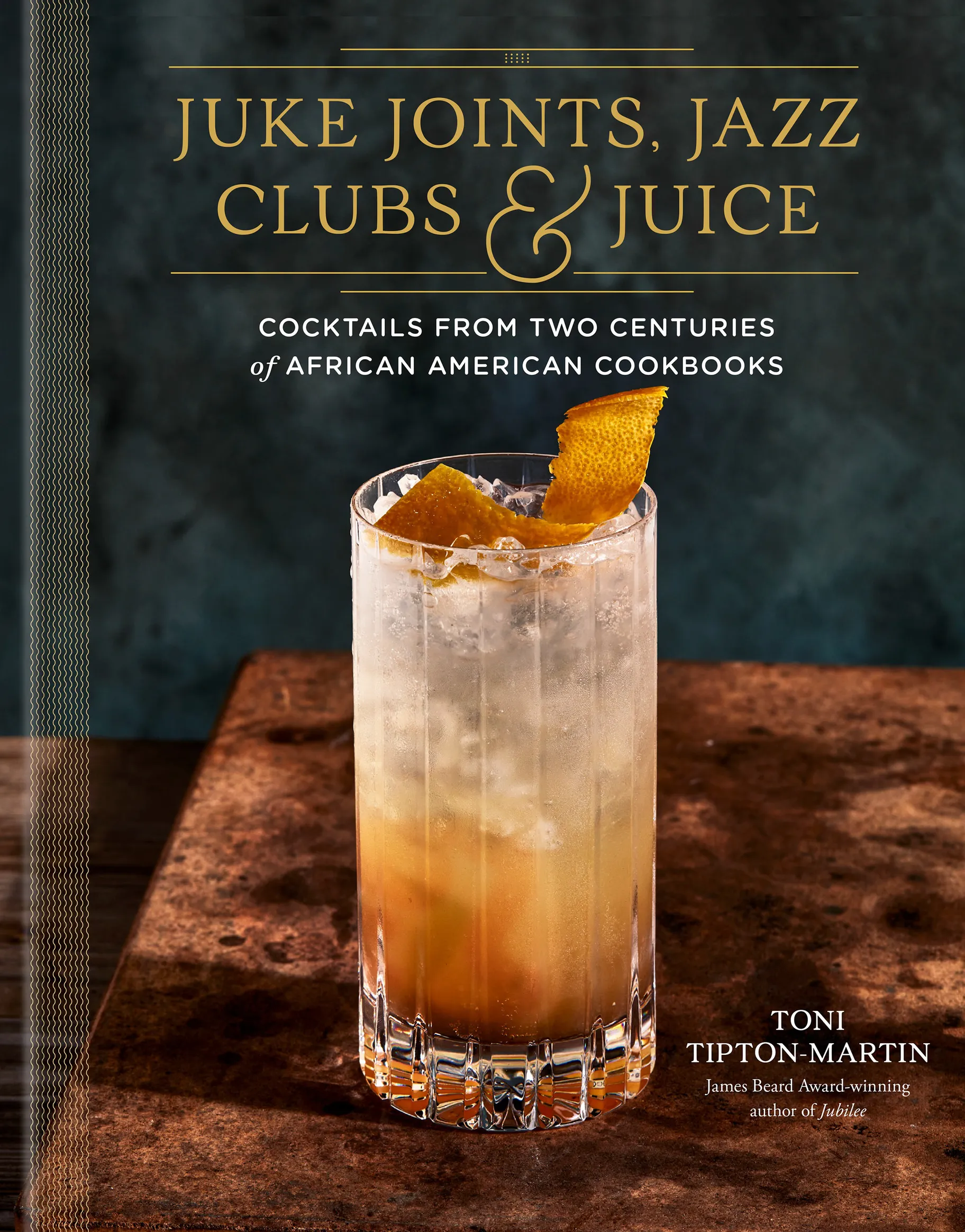

With an apricot brandy and tangerine liqueur, this single serving claret punch pairs perfectly with a Thanksgiving meal. Photo by Brittany Conerly.

Much of early African American libation is rooted in innovation and creativity due to circumstance. What is the role of women and booze in the antebellum years?

Well, what's really interesting is when we think about making cider or beer, for example, those are two crafts that fall squarely in the realm of a woman's work. You're cooking, basically, making a mash, over heat, straining it then applying various other processes to distill out the solids and arrive at the clearest liquid that one can find. African American women have a known history that can be traced back to West Africa of making beer and palm wine. Both of those were libations that might be used ceremonially during funerary experiences. They could be part of hospitality rituals where a host would make sure that you were served something light before the meal. These traditions can be traced all the way back to West Africa. What is unfortunate, and another little fact that surprised me, was how much enslavement really corrupted that whole process. What African Americans were doing in the motherland became, maybe, a kind of a salve for the horrors of what they were going through. The planters would use the corn whiskies and other things that they were making to try to soothe the pain by making sure that the enslaved had distilled beverages to drink. It's kind of a complicated story to tell.

Who were the earliest notable mixologists that you encountered in your research? And what was the first cookbook that had tested recipes for cocktails?

What's interesting about that is that most everyone refers to Tom Bullock, who published The Ideal Bartender in 1917. That is a complete volume full of classic recipes that everyone will recognize, if you have any interest in bar culture. What I learned from my friend Robert Simonson was that there was a second mixologist to publish two years later [Julian's Recipes], and his name was Julian Anderson. His collection is very similar to Tom's in that it's classic bartender speak. He's got these recipes, some of them have funny titles, even complete with body part names. Those are the two guys that get all the attention.

But to my great surprise, even before them, there was a woman who published a cookbook of recipes, and she's the first that I've encountered to have a full chapter on beverages and mixology. Her name is Atholene Peyton. She wrote a book called The Peytonia Cookbook. It's very rare. Few people know about it. I think there are only two copies of it that are known. One is at the University of Kentucky and one is with the National Park Service. They were gracious enough to share the pages of it with me because of its fragility. It's so fun to know that a woman got there first. She has recipes for rum punch and cherry cordials and all of the kinds of beverages that we've been talking about.

Toni Tipton-Martin says that when her parents entertained, her mother would set up a lavish buffet in the basement while her dad's bar was initially built from her grandmother's hideaway bed. Photo by Clay Williams.

Let's talk about batch cocktails, which we're seeing much more often now, and seem to have always been a specialty of caterers. Do you have a favorite batch or punchbowl beverage that you would suggest for the holidays?

Well, Rum Punch is always a favorite. It's obviously a familiar term. Everybody kind of knows Rum Punch, if they've traveled in the Caribbean. But one of my favorite stories in the book revolves around the Claret Punch. When my son, who is a bartender and was helping me with this recipe, and I put our heads together about batching up some of these recipes that initially were single-serving drinks in one or another of the cookbooks, we discovered in making this by coincidence at Thanksgiving that it was delightful served prior to the Thanksgiving meal. It's got an apricot brandy, there's some tangerine liqueur in it and it's really festive because of the sliced fruit that floats on top. So that would have to be one of my favorites.

Let's talk about eggnog for a minute. What are some of the different versions of it that you found in your research?

This book has several versions of eggnog. The recipe for it, interestingly, is called Bowl of Eggnog, because that's the term that Tom used to describe it. But multiple mixologists had versions of it. There's this really cool thing called a Tom & Jerry cocktail. It was actually made with a batter, a thick base of creamed eggs and sugar, then diluted with spirits. It's sort of the thing that we derive eggnog from, the same kind of a foundation that has spirits layered in but with eggnog, you tend to use cold milk rather than this paste that's mixed with boiling water. I love to talk about the Puerto Rican version of this. It's called Coquito and it gets a tropical flavor from coconut and sweetened condensed milk.

I have to ask you about the origins of the term "juke joints." Where did the phrase come from?

That's a really interesting question. When you're on the ground in the communities, like in the Mississippi Delta, you hear the words "juke joints" a lot but you also hear other terms that were associated with gatherings in the woods, off the beaten path, primarily in agricultural communities where people had been working hard all week. Then, on the weekend, they just wanted to let their hair down outside of the gaze of the sharecropping landowner. Some of those places were known to be a little bit rowdy. Others were similar to cafes, where women would operate rooms from their homes where they would make really great food, mix up some moonshine and they could serve the people in their community. There are multiple references to how we arrive at that name. There are theories. One of them is that it's connected to a West African term "juke," which can mean some disparaging things that center on troublemaking. But one of the most common accepted answers is that they're tied to the jukebox. Over time, when live music was no longer happening in these spaces, the people who were partying there began to listen to music played in a box on records. And that's the time "juke joint" became more popular.

"Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs, and Juice: A Cocktail Recipe Book" pays homage to the people behind African American mixology. Photo courtesy of Clarkson Potter.

I would love it if you could leave us with some contemporary mixologists that you have your eye on.

Asking me to name anybody in whatever subject is like asking a mom to name her favorite child, so I'm always reluctant to do that. But I will tell you that I've gone to great lengths in this book to cite every current African American who has published recipes, who has reclaimed this legacy for themselves and for others. I've adapted some of their recipes as an homage and honor to them for what they've achieved in their own worlds. So my favorites are there. You'll be able to see who I lean on and who I speak to. I will take one little point of personal privilege and say, obviously, that Tiffanie Barriere, who has been a mixology mentor to me, is a cherished, cherished part of this process. She's known as The Drinking Coach, and anyone can follow her online. She is involved with Tales of the Cocktail. She's award-winning and she recently received an honor in my name from the IACP, the International Association of Culinary Professionals, but she is not currently on staff at a bar.

Claret Cup

Serves 30

Cups are wine-forward drinks decorated with fruit and herbs. Classic cups can have a base of either wine or beer. For the wine-based, claret (a red wine) and lemonade form the foundation, with brandy, green Chartreuse or Curaçao, and pineapple or cherry juice stirred into the more elaborate mixes. Despite the name, cups are served from pitchers or other large vessels, similar to punch. Cucumber was a popular adornment that is back on craft-cocktail menus.

Bertha L. Turner, a state superintendent of domestic science who, in 1910, cul- tivated recipes from members of the Colored Women of the State of California for The Federation Cook Book, fortifies her Old Pacific Slope Punch with twice the claret I suggest in my adaptation that follows. Despite its fruity foundation, this cocktail is not as sweet as the version in John B. Goins’s 1914 book, The American Waiter. (Goins was an expert in early twentieth-century lodging and hospitality, not a recipe specialist.) And the addition of seasonal grapefruit is a nice touch that delivers potent citrus notes without dominating the wine and Champagne flavors. The word claret is derived from the Latin meaning “clear.” It is a British term used to group the red-wine blends of Bordeaux into one category, which gives you lots of flexibility when it comes to choosing the wine for this recipe. Try making it with your favorite Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot. Served in small tea cups, this cocktail is good as a prelude to Thanksgiving dinner.

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon granulated sugar

- 2 tablespoons warm water

- 3 oranges, sliced

- 2 lemons, sliced

- 1 pineapple, peeled, cored, and sliced into rings

- 1 ounce (2 tablespoons) Abricotine or apricot brandy

- 2 ounces (¼ cup) Curaçao or ¼ cup homemade Tangerine Liqueur (page 37)

- 2 (750 ml) bottles claret of choice

- 2 (750 ml) bottles Champagne or other sparkling white wine

- 2 cups sparkling water 1 large block of ice

- 1 grapefruit, thinly sliced and cut into half-moons

Instructions

-

In a large bowl, stir together the sugar and warm water, stirring until the sugar is dissolved. Add the orange, lemon, and pineapple slices, and stir to thoroughly

coat the fruit with the syrup. Let stand for 30 minutes, allowing the fruit to macerate. -

Add the Abricotine, Curaçao, and claret, and stir for 1 minute. Cover and refrigerate for 3 hours.

-

Strain the mixture through a fine-mesh sieve, pressing on the pulp with a spoon to extract all the fruit juice. Pour the infused wine, Champagne, and sparkling water into a punch bowl. Stir gently to mix. Add the ice block and garnish with grapefruit slices. To serve, ladle the drink into Champagne flutes

or punch cups.