Sidled up to a wooden table in front of the fireplace at the El Cholo on Western Avenue, owner Ron Salisbury is blunt when asked about his prospects as a teenager growing up in Los Angeles.

"I wasn't a very good athlete. I was a year younger than all the girls. I didn't have much of a start,” he says. “If you'd looked at me in high school, you would've said, 'His life's gonna turn out pretty ordinary.'"

But fate can be funny like that. Salisbury's life has been many things, but average is not one of them.

His grandfather was a carpenter. His grandmother was an exceptional cook. In the 1920s, they left Arizona, searching for the American Dream. They found it in Southern California. In 1923, Alejandro and Rosa Borquez opened Sonora Café in the shadow of the newly built Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Two years later, they changed the restaurant's name to the one it still carries today.

While working as a waitress, their daughter, Aurelia, met and fell for a customer, George Salisbury. They married and opened an outpost of the family business on Western Avenue in Mid-City. In 1931, they moved it into a bungalow across the street, at 1121 S. Western, in what was then a largely residential area.

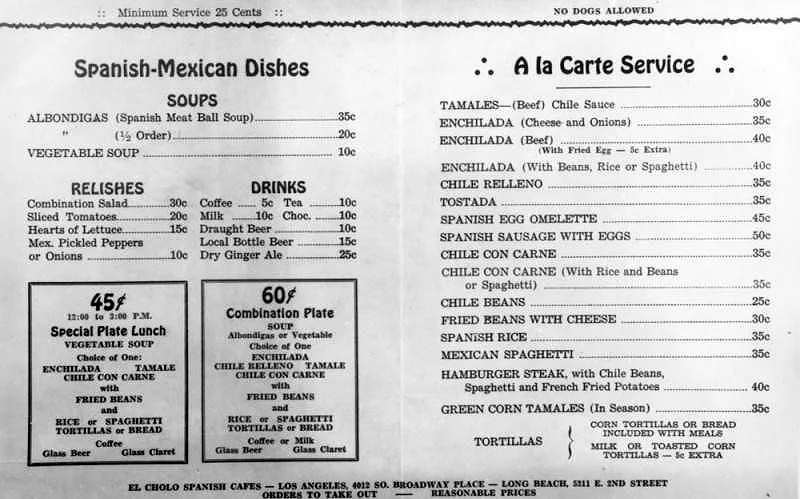

It was a humble establishment with a tiny menu. You could order an enchilada, a chile relleno, or a taco and, if you wanted, a plate of beans and rice to go with it. While 99% of restaurants come and go, this one endured.

More: Inside El Cholo: How the old-school Mexican restaurant has thrived in LA for almost a century

A century later, El Cholo is a Los Angeles institution. More than that, it's the oldest Mexican restaurant in California and the third oldest Mexican restaurant in the United States. (The Original Mexican Cafe in Galveston tops that list and the El Charro Cafe in Tucson comes in second.) This year, it celebrates its 100th anniversary. To honor this milestone, KCRW’s Elina Shatkin, along with contributor, Los Angeles Times columnist, and El Cholo superfan Gustavo Arellano, paid Salisbury a visit.

At 90, Salisbury is nearly as old as his restaurant and as sharp as a freshly honed chef's knife. He has seven children, 19 grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. All of his kids have worked at El Cholo, as have most of his grandkids, and approximately half of his great-grandkids — six generations participating in the family business. He still works seven days a week, and has stories on stories on stories. After 69 years running the place, it'd be strange if he didn't.

[You can listen to the interview we ran with Ron Salisbury on Good Food by clicking the link in the left sidebar. Below is an extended version of that conversation. It has been edited and organized for clarity.]

Early Days

Neighborhood History

Taking The Reigns

Culinary Racism

Authenticity

Nachos

An Evolving Menu

El Cholo Grows

Expansion to Utah

Sticking Around

Running the Restaurants

Famous Friends: Nolan Ryan

Famous Friends: Michelle Phillips

Famous Friends: Emmylou Harris

Famous Friends: Louis Zamperini

Miscalculations

Work/Life Balance

The Secret to His Success

Celebrating the Centennial

The Next 100 Years

A 1938 menu for El Cholo offers plate lunches for 45 cents and combination plate for 60 cents. Minimum service is 25 cents. Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Early Days

Elina Shatkin: You're 90. You were only two years old when the restaurant opened its Western Avenue location. How much do you remember about the early days of El Cholo?

Ron Salisbury: When you're first born, you have these little glimpses. Maybe it's running across the lawn with a bunch of kids. Maybe it's swinging on a swing. Maybe it's sitting in your bed at night. Maybe it's the first Christmas tree. I can't have earlier memories than actually sitting in this restaurant, the excitement and the smells and just the joyous feeling that was here. The people were so happy to be here. And as a little kid, I picked up on it. It was awesome.

A 1937 picture of the exterior of El Cholo. Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Neighborhood History

Shatkin: We are in the original El Cholo building. How has the interior and exterior changed over the last century?

Well, a lot. If you look up and down the street here, there's maybe one house left. It was all these California bungalow style...

Gustavo Arellano: So it was a residential neighborhood, basically.

Strictly residential. Before La Cienega became Restaurant Row, this was Restaurant Row. We had our little house here. We had Toyo, which was a Japanese bar restaurant across the street. There was The Irolo, which was a restaurant, over here. We had Charlie's Diner, which is a dining car on the corner. We had McDonell's, not McDonald's hamburger, McDonell's drive-in. We had Stan's drive-in up on Wilshire and Western. We had the Blarney Castle. We had the Nickodell. We had all these restaurants along Western Avenue. So I feel really close to a lot of history on one street.

This corner here got named by the city in honor of my grandparents, these humble people who came here from the territory of Arizona. They were Hispanics and they decided to open a little restaurant. It wasn't a glorious restaurant. It wasn't glamorous. But you could come and you could have really good home-cooked food and it was run by people who cared deeply about how you were treated. It all started with just the American dream and that, to me, was really a very touching thought.

Artifacts from the early days of El Cholo are displayed in the restaurant's Western Avenue location. Photo credit: ElinaShatkin/KCRW

Taking the Reins

Shatkin: How did you get involved in the business? Were you involved with your family's restaurant your whole life?

Salisbury: I grew up in the restaurant business. In those days, you worked as a teenager after school when they needed you. When I went away to college, when I came back, even when I was 19, 20, my dad entrusted me to actually run the restaurant. I wasn't much of a student. I didn't take life seriously. I never thought much about it. I just wanted to have a good time when I was younger. Then, when I got married my last year of college, I realized it was time to get serious. I realized this is what I'm going to do.

It's always been huge in my life. I had an older cousin who was supposed to take over the restaurant. He didn't because he wanted to go into television and he's kind of the black sheep of the family. I didn't want to be a black sheep. I always had a love for the restaurant. I loved what was going on here, I loved being part of it and I was very proud of what it was. It was a humble little restaurant. So that's how I came in here.

The sign outside El Cholo reads "Spanish Cafe" although the food originates in Sonora, Mexico. Photo credit: ElinaShatkin/KCRW

Culinary Racism

Shatkin: One thing I'm curious about, the sign says, "El Cholo, Spanish Cafe." Your grandmother, who was the original cook of the restaurant, she was Mexican, from Sonora. But they called it a Spanish cafe. Why?

Okay, back in the 1920s and '30s, if it was Mexican food, it was not going to be healthy and sanitary. You called it Spanish but you really knew it was Mexican. So that sign says "Spanish food." I'm not gonna take it down because it's a historical point. It brings up this interesting little conversation. It wasn't viewed as sanitary food so my dad made a point to have a big open door to the kitchen, so when you're in the restaurant, you could look in there and see the kitchen and see how clean it was. It was a cultural thing that Mexican food was not clean.

Shatkin: Unfortunately, I feel like some of that culinary racism extends into today. Gustavo, you could probably speak to this about how certain kinds of cuisines and restaurants are seen as high-class and others are not.

Arellano: I always thought that this idea that Mexican food, the food that your grandmother was making, the food that you continue to make, is simple food is preposterous, because the preparation is so intricate. The flavors are so incredible. So to call it a peasant food, a simple food, that's just stupid — and definitely racist.

No, it really is. John Sedlar is a really well known chef. And John was doing upscale modern Mexican. He told me one time, "You don't realize, Mexican food is one of the most difficult foods to do correctly." Because as you pointed out, it's intricate and the subtleties of making it are really difficult, much more difficult than most foods.

The No. 5 combination plate at El Cholo features a chile relleno and a rolled beef taco. Photo credit: ElinaShatkin/KCRW

Authenticity

Arellano: There was a time when El Cholo was the "it" place. Then, maybe people overlooked it or thought that kind of food had passed. But I think in the past couple of years, there's really been a renaissance of people appreciating what El Cholo is. How do you feel?

I hope so. Looking back now, the 100 years, I'm doing a lot of reflecting, probably more than I've ever done before. I read a lot of these things on Yelp and everything. "It's not authentic," and on and on. I think, no, wait a minute. In 1923, it was my grandmother's, who was a wonderful cook, it was her homegrown recipes [from Sonora].

And we haven't changed! We take pride in the basic things. We have not changed that. At one time, it was as authentic as you could possibly get. So yeah, to me, it's still authentic in its own way.

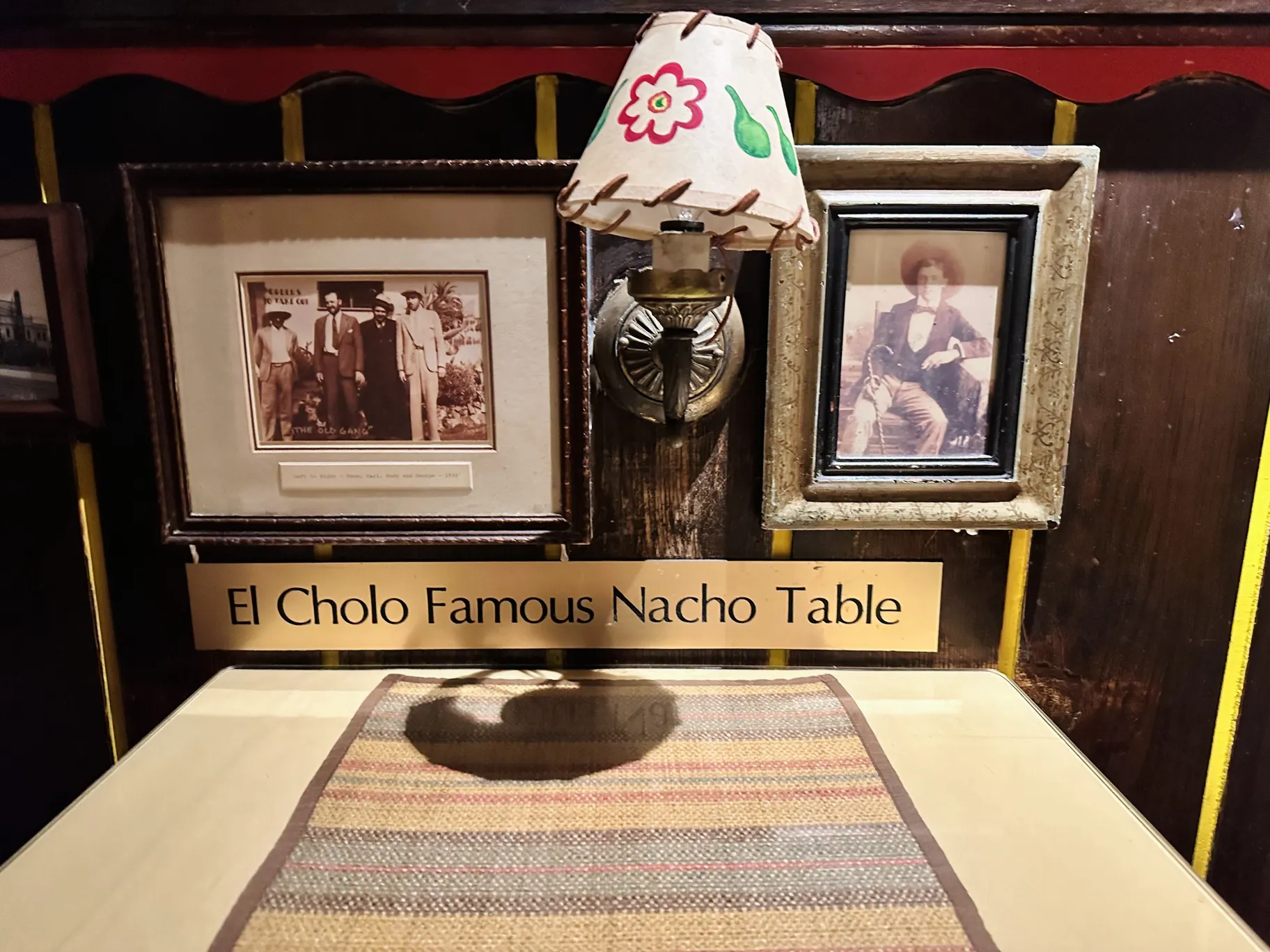

If you sit at El Cholo's nacho table, which Ron Salisbury describes as the worst table in the house because its proximity to the kitchen and the amount of foot traffic that goes by, you get a free plate of nachos. Photo credit: ElinaShatkin/KCRW

Nachos

Arellano: One of the most memorable things about El Cholo is the menu. It's an encyclopedia of Mexican food trends in the United States. You have all these dishes and the menu lists the year they were introduced. This is when carne asada tacos came onto the menu. This is when fajitas came onto the menu. El Cholo has always been adapting to whatever people at the time think authentic is.

That's a really good point. Items were added to the menu over the years, it was a natural thing. There's the great story about nachos. Nachos were not known in California. Carmen Rocha, who came to work here [from San Antonio].

Carmen brought nachos here. In those days, we didn't rotate stations. Everybody had their own room. So Carmen had the same room she was operating in, and she would make nachos off the menu for people who would come and sit with her. Sometimes, they would sit with someone else and they would say, "Carmen always makes me nachos. Would you make me some nachos?" We realized we had something that was really big. Let's put it on the menu. When Carmen passed away, the LA Times had a third of the page obituary for her. The menu is a real history of Mexican American and food trends, in general.

On opening day in 1927, four El Cholo cooks prepare tortillas and other food at the restaurant. Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

An Evolving Menu

Shatkin: Looking at the menu, we see chili con carne from 1923. We see Carmen's original nachos from 1959. We see fajitas from 1984. Then all the way up to 2019, when you added a Mexican chopped vegetable salad. Tell me about your favorite dishes, both the old school and the new ones.

There was a time when combination plates were not on here. If you look at the original menus, we have some posted around the restaurant, that menu was so simple. I remember in the late 1930s, a Mexican restaurant opened a couple of blocks away from here. They put in combination plates and they were real busy. I remember sitting in the car with my dad outside watching the people coming in there. Of course we regrouped and put combination plates on the menu.

The Taste of History [combo plate] is really recent. That is an ode to my grandmother, when there was nothing else but enchilada, taco, relleno, tamale, beans and rice. We've combined them onto one plate so, in effect, you can have a taste of our early history. It's one of my favorite plates.

It's probably about the fifth or sixth most popular item on the menu. The chicken mole enchilada, we needed something for our 100th anniversary, and it was the right time to finally bring mole into the picture.

Arellano: I'm still waiting for it El Cholo to bring in birria. That's a big trend that's been all over restaurants in Southern California over the past seven years or so.

So how do we work that in?

Arellano: You talk to your chefs. All it is is a good stewed beef and you put it in some tacos. There you go. Birria de res tacos. You could put it on the menu so it says 2024.

The expanded dining room at El Cholo on Western Avenue features this patio dining room. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

El Cholo Grows

Shatkin: El Cholo has expanded a bunch over the years. How did that happen?

There was never any [plan where] we're going to grow so many restaurants. We have one restaurant. All of a sudden, something comes along and you look at an opportunity and say, "You know what? That would make a great El Cholo." Then maybe six or seven years go by and all the sudden, you run into another building or someone comes by.

The restaurant downtown, which is near Staples, or Crypto now, I wasn't in the mood for the restaurant. A woman had put together a group of investors to do an Italian restaurant there. It wasn't working out. Someone told her, "You know, this would make a great El Cholo." It's a great, old 1927 [building]. It was a golf shop in those days. So we were sitting over there in the bar, and she came to me and said, "Would you be interested?" I said, "No, I'm really not. Life is good. I don't need it." She started telling me the sad story of how she needed to save it and then she started to cry. And I can't deal with a crying woman so I said yes. Those are the kinds of reasons we open up restaurants.

Shatkin: How many El Cholos do you have now?

We personally are running six right now. We're opening one in Salt Lake City this summer and my son Blair has his own independently run one Pasadena.

A poster promotes El Cholo's first restaurant outside Southern California. It is slated to open in Sugarhouse, Utah, in the summer of 2023. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Expansion to Utah

Shatkin: Why Utah as the first El Cholo outside of Southern California?

Everybody tells me I'm going back on my word. I always said, "You definitely want to have all the restaurants so that if you had to, in one day, you could drive to 'em and visit with them all." I have a love for the state of Utah. I've been going there for years. I went to school there in the '50s. I really fell in love with the way things are happening there.

California, every time they pass a law or something, it makes it more difficult for you to run your restaurants. It's heading in a direction which, if it continues, is almost frightening. I wonder what restaurants will be like in 10 years. Will it be artificial intelligence running these restaurants?

The state of Utah is still like California was many years ago. Here's how different it is. When we put in our plans to be processed, the city of Salt Lake assigned someone from the department to shepherd the plans through and make sure they went through. In California, I was talking to a friend of mine who has [spent] something like nine months trying to get the Department of Water and Power to hook up to electricity for a commercial building he has.

It's a great lifestyle there and I think it's a great opportunity. I went to one restaurant in Salt Lake that's doing business right now. At 11:30 in the morning, there was a line to get in. I won't mention it, but I had a hard time eating the food.

Shatkin: What is the Mexican and Mexican American food scene like in Salt Lake City?

You have tons of Californians moving there and among those tons of Californians are a lot of people who have grown up eating at El Cholo. That's the joy of being part of El Cholo. I can run into strangers and suddenly, we have a great conversation going because they've eaten at El Cholo. I can go places in the world and we have this thing in common to talk about. And I like being in Utah. I go there once a month for three days by myself. I talk everybody out of going with me because I want to be by myself. I go there until I get tired of talking to myself, then I come home.

Arellano: I think El Cholo is just such a great ambassador for what California is that I'm surprised you haven't gone out from California already. You have In & Out and other ambassadors of California food already doing that. Why did you wait so long?

Gustavo, I'm 90 years old. I wanted to do something dramatic and prove that at 90, you can still do something. That's part of it, really. Again, the opportunity just came along. I think there's so much there that will help us. I think I'm positioning maybe those who come after me to be in a place where if they want to grow the restaurants and add to them, it'll be a really fertile area.

Gustavo Arellano interviews Ron Salisbury at El Cholo. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Sticking Around

Arellano: I don't know why people want to get into the restaurant industry because it's just so volatile. How does it feel to be the inheritor of a restaurant that has lasted this long? And not only that, the inheritor of a Mexican restaurant that started at a time when most people didn't know what Mexican food was, and it still is very successful at a time when we all eat Mexican food.

All I can describe it is intense love. I'm watching "1923," the prequel to "Yellowstone." There's a love story in that thing that's intense. That was me in the restaurants, unfortunately or fortunately. I'm not gonna let this restaurant down. I want it to be everything that can be, and it's not for me. I had the highest respect for my grandparents and my parents. I listened to everything they said. I just worshiped how they viewed life.

My card says "the grandson of the founder." We own The Cannery restaurant in Newport Beach. A few years ago, a gentleman came in. He was the starter of a really huge chain of restaurants that, again, will go unmentioned. He handed me his business card and it said "CEO and Founder." I thought oh, that's a big, heavy title. At that point, I'd never put a title on my business card. [I thought] maybe it's time for me to put a title on this. So if he is the founder, who am I? I am the grandson of the founder. People say, "What does that mean?" It means that I better respect and protect what they did, and if I can, in any way, make it better, do that. That's my job. Which pretty well covers everything.

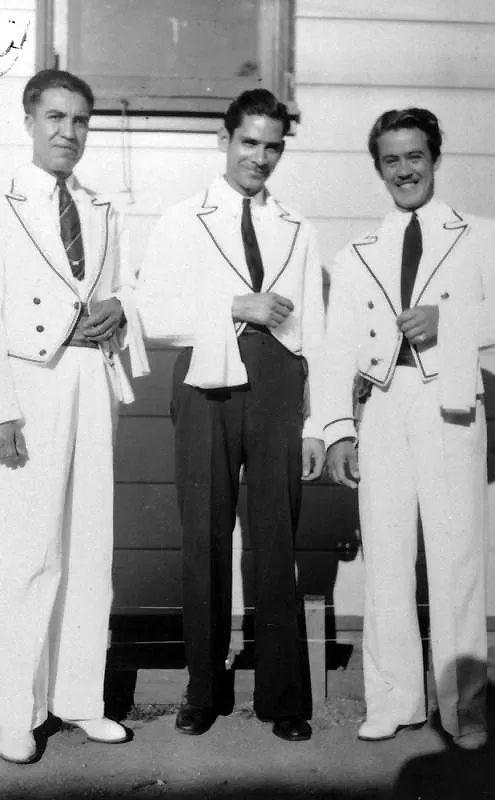

Three waiters in white jackets pose in front of El Cholo in 1938. Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Running the Restaurants

Arellano: Your trust in your employees has created this loyalty that you don't see in other restaurants. My colleague at the LA Times, Lucas Kwan Peterson, he highlighted five employees from El Cholo with a combined 200 years of work here.

You can imagine what it was like coming in and knowing all these people. I tell a manager, "When you come in, the first thing you do is you go back and talk to the dishwasher. The dishwasher gets ignored. It's the worst job in the restaurant. So you go back and you set the standard for the day, talk to the dishwasher, tell him how's he doing, check his work. Then, you go check other things. Then we're all equal." It's a joy to be a team.

Another baseball story. I forget who it was, some famous player, he said, "I'm going to be elected the Hall of Fame, I make all this money, I'm really famous." But he said, "Nothing beats winning the World Series and sitting around a locker room, looking at each other and saying, together we did this." I want the same thing here. I want people to look at each other and say, "I'm really proud to be here and together we did this." It's not me running the restaurant, it's the manager who's really running the restaurants. Those are the people who really run the restaurants. They're here every day, and they represent it. I just come in and mess around.

One of the old school dining rooms at El Cholo. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Famous Friends: Nolan Ryan

Arellano: El Cholo is famous for some of the famous clientele that you've had. Jack Nicholson, Michelle Phillips, Tom Hanks. What are some of your favorite stories with some of your famous customers, so of the ones that I mentioned or other big names, what are some of your favorite stories?

Legendary pitcher Tom Seaver was a student at USC who grew up eating at El Cholo. Tom was responsible for the Mets going from last place to winning the World Series in 1969. When they came to town, he would bring a player with him and have lunch before a game. So I walked in one day and Tom was sitting in the booth. "Hey, Tom," I said, "how are you doing?" He says, "Come here, I want to introduce you to this kid. I bring this kid along to shine my shoes." Well, it was Nolan Ryan.

We have an El Cholo in La Habra. Nolan and his family, when he went to the Angels, they started eating there. I was in there one night and we met and we started talking. We went and had lunch, and it developed into an incredible, long-term friendship.

Arellano: He's my favorite baseball player of all time.

Ron Salisbury: And he should be. There's a documentary on Netflix called "Facing Nolan." It's an incredible story about the entire family. My son worked for him for a year on his ranch. Another one worked for the baseball team that I have a little share in with him down in Round Rock, Texas. His two sons, Reid and Reese, came out and worked for us for a year. So we had this relationship.

Everybody feels they can play baseball. Maybe I couldn't play football or basketball, but every guy says, "I can play baseball." So I said, "I wonder what it is like to face Nolan Ryan, who throws the hardest of anybody in life." And I said, "Nolan, it's your last year. Could I face you one time?" He said, "Come on down to spring training." So I went down.

One night, after spring training, I took out a catcher, took out a photographer and he threw the ball so I could actually get the bat on the ball. I've got that on video. Then he said, "Okay, it's the bottom of the ninth, there are two outs, and I'm working on my eighth no-hitter." What he's really saying was, "I'm going to throw the best I possibly can." I couldn't see the ball. There was just a blur that went by. Now I know what these major league hitters have experienced. Not a lot of people can say that.

Jack Nicholson is just one of the many celebrities who are fans of El Cholo. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Famous Friends: Michelle Phillips

Arellano: Michelle Phillips was at the press conference when they announced the renaming of the area around here in honor of your grandparents. What's her story here at El Cholo?

Well, her story is a Jack Nicholson story. She was dating Jack, and he said to her one time, "Do you like Mexican food?" She said, "I don't know what it is." He said, "Well, I'm gonna take you to the best Mexican food there is." And he brought her here. From that point on, she has been one of our best supporters. If you call here and the recorded message comes on, that's Michelle. If you call the Cannery or Louie's, Chuck Finley, the pitcher for the Angels, that's his voice.

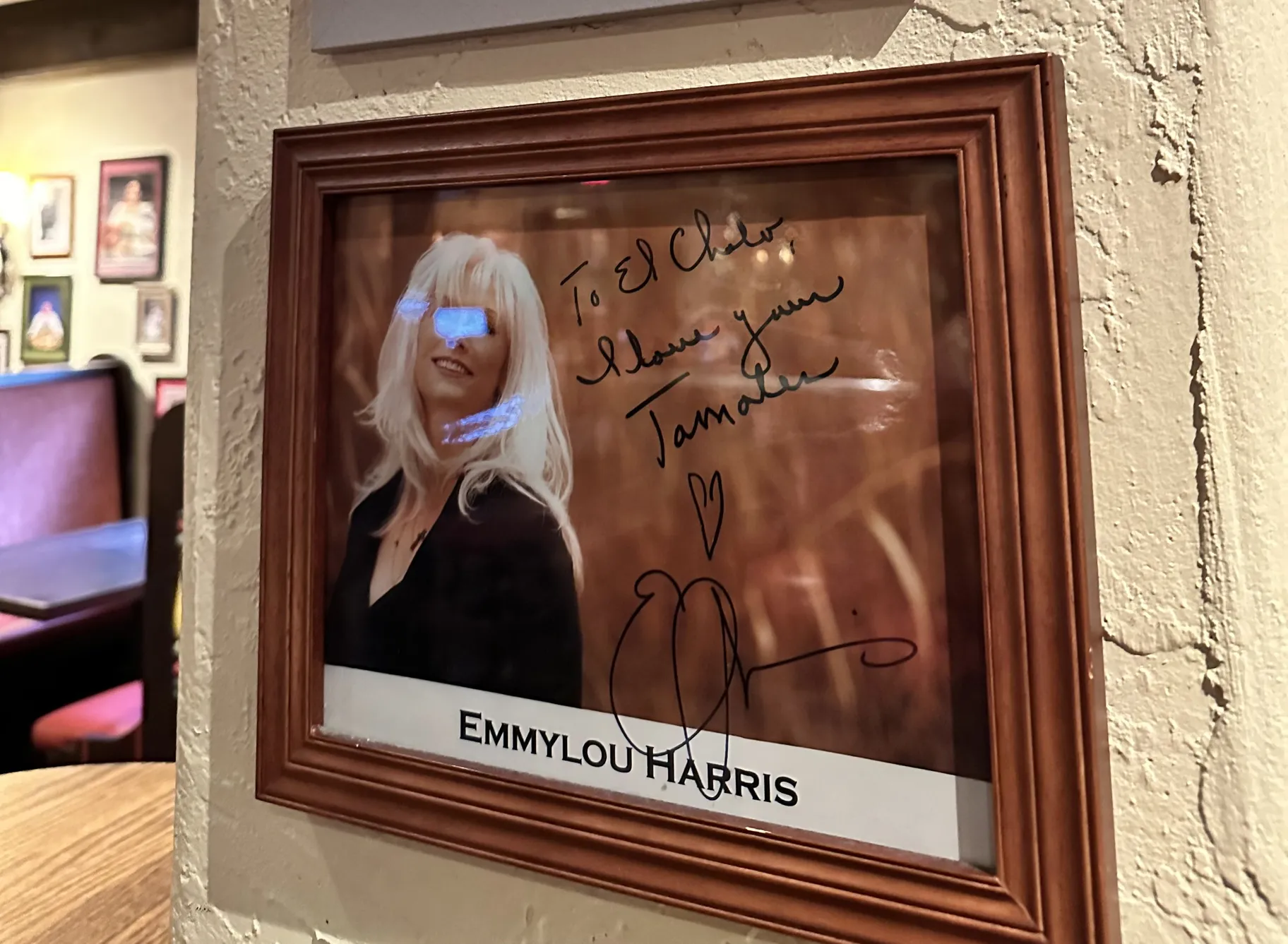

Emmylou Harris is a fan of El Cholo's green corn tamales. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Famous Friends: Emmylou Harris

Arellano: [Emmylou Harris is] another fan?

I'm gonna tell you that one. I would go to my little place in Utah, I would open up the window so I could hear the river running by, I'd put the fire in the fireplace, I'd kick off my shoes and I'd put Emmylou's music on. Then I thought, "My gosh, her music entrances me so much. I wonder what it would be like to have dinner with her." So I wrote her a nice letter and she accepted. So I went to Nashville and went out to dinner and now we've been really good friends. She bakes me cakes and we send her green corn tamales. We did [a concert at the Cannery in Newport Beach] to help raise money for her dog rescue.

This room at El Cholo is named after athlete and war hero Louis Zamperini, who was a lifelong friend of Ron Salisbury. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Famous Friends: Louis Zamperini

You mentioned people who I've gotten to know... Louis Zamperini, whose book "Unbroken," was a #1 bestseller on the New York Times, was my babysitter when he was a student at USC. He was a great track star who ran in the 1936 Olympics. Hitler asked for a personal audience with him, so he met Hitler. And I thought, "What was he like?" [Louis] said he was kind of effeminate, which was an interesting observation.

Louis was lost at sea, we thought dead. Then, suddenly comes back when they rescued the prisoners in Japan, and then he comes back into my life. He was probably the most amazing person I've ever known in my life. We were friends until he passed away at 99. He wrote me a letter saying, "One of the main things that kept me live in the Japanese prison camp was wanting to come home to El Cholo and have a #1 Combination." And that's all he ever ate when he was here.

Shatkin: That's the cheese enchilada and the rolled beef taco.

I sometimes get tempted to erase it as the “#1” and call it “Louie's Combination.”

Inside the kitchen at El Cholo on Western Avenue, cooks prepare for the day's customers. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Miscalculations

One of the biggest curses that ever came was tortilla chips and hot sauce. We used to serve hot tortillas with butter and you'd put a little hot sauce on them. You didn't fill up on them, you had one or two. With chips, you can't get them in your mouth fast enough and your appetite gets ruined. If I could do anything to change the Mexican food industry, I'd get rid of the chips because it ruins the opportunity to really taste and savor the food.

Anyway, going back to your question, we were in the kitchen, frying the tortilla chips and my dad looked at me and said, "You know, someday, somebody's going to put these in a bag and sell them in supermarkets." And I thought, "Dad, you're crazy. Why in the world would anybody want to buy tortilla chips?" That's one of my famous miscalculations.

Arellano: One of very few.

Salisbury: Well, I also have the one with wine. We were a beer drinking nation. And years ago, a gentleman from France opened a restaurant and he said, "I'm going to teach the American public to drink wine." I thought, "You are crazy. Americans will never, never drink wine." So I'm pretty famous for a lot of miscalculations.

The first El Cholo opened in 1923 near the LA Coliseum before moving to Western Avenue. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Work/Life Balance

Shatkin: On a day-to-day basis, how much are you doing in terms of running the restaurants?

I get up every morning thinking, "Oh, my gosh, I've got some problems to go out there and solve," and how great that is. I have good genes. But also, the opportunity to get up every morning, the first thought that hits you is, "What am I going to fix and solve out there?" is huge. Other people at my age, they get up and say, "What am I going to do today?" And sometimes there's not a good answer. I'm very fortunate.

You asked earlier, what is it about the restaurant business? It's not for everybody, but if it's for you, there's no better business. It is so rewarding, so fulfilling, so full of life and people. You're thinking all the time, "These are human beings coming in here. What can I do to understand them?" That's a great opportunity. I feel sorry for some of these guys that their businesses are closed on Saturday and Sunday. They've got to go out and figure out how to make themselves happy by playing golf or gardening or something. I know what I'm going to do for seven days. I get up and I go until my gas tank is empty.

But this is not for everybody. There's something about this new generation. We have a group of them working for us that are awesome. I'm so impressed with their awareness, with their focus, with their wanting to do the right thing, with their wanting to learn. They're really incredible. But again, it's not for the majority of people.

On opening day in 1927, four El Cholo employees pose for a picture by the cash register. Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

The Secret to His Success

Here's how involved you get. The other night, I told my wife, "I'll be home at 6:30 and take you out to dinner. But I have to go down to the restaurants and take care of these few things." I get down there, talking to people. I start to walk out, I look at my watch. It's 9:30 p.m. I'm three hours late to take my wife out. This is not going to be good. What am I going to say? I pull out the phone and there's a text message that says, "I'm not feeling well. Please forgive me if we don't go out tonight." So I forgave her.

But that's how involved it is. It's so consuming. You get in there and you're talking to people and you're enjoying the conversation. You're making things happen and you're in there figuring out how to improve something or you're learning something from somebody. You learn more from your guests and your staff than you do from your managers than anybody else. Because those people will tell you the truth of everything that you want to know. And that's what you want to figure out — how to make the experience better.

It's important to incorporate people, it's important to create stories. I hope this restaurant is filled with stories. You want the restaurant to be human, not just someone that just serves food. I think that's one of the keys.The greatest server we ever had, her name was Anne Howe. I asked her one time, "What is it about this restaurant?" She said, "It snuggles you." You're comfortable here. That's what you want. How many trendy restaurants are still around?

A mural on the wall of El Cholo depicts Ron Salisbury and one of the restaurant's chefs. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

Celebrating the Centennial

Shatkin: What are you doing this year to celebrate El Cholo's 100th anniversary?

I saw it as an opportunity to do something special. I committed us to raising $1 million for pediatric cancer research. Half of the money will go to Children's Hospital LA, half will go to Children's Hospital in Orange County.

For $25,000, we'll name a margarita after you. A man snapped that up right away. He said he and his wife ate here twice a week. She passed away at a very early age so he wants to come in here and see her name on that margarita.

We have a jellyfish aquarium going into the Cannery, so I'm putting up naming rights. If anybody wants it, $100,000 will name the aquarium after you. We're doing things like that.

We have a free nacho card. For a $100 contribution, you can eat free nachos all year long.

You can also qualify to own El Cholo for one day. When we draw a name out of the hat, somebody will fulfill a fantasy of owning a restaurant.

Also, I recognize that we didn't get here alone. We got here with a lot of iconic restaurants — Philippe's, The Pantry, Pink's, Musso & Frank. So we got all these older restaurants to give us gift certificates and you can win these gift certificates.

We have a $100 margarita in handblown glasses coming from Mexico, and you get to keep the glass.

The city of Los Angeles named the intersection at Western Avenue and 11th Street in honor of Alejandro and Rosa Borquez, who founded El Cholo in 1923. Photo credit: Elina Shatkin/KCRW

The Next 100 Years

Arellano: What do the next 100 years of El Cholo look like?

I won't be here. I don't know.

Arellano: I don't know, you have good genes.

All I can do is hope. It's hard because you're older and you expect things out of your descendants, to view life the way you do. And they're not going to because they don't have the experience. My youngest son is the one who's taking over because my other children are at retirement age. I'm very fortunate that he deeply wants to. Besides, he's a lot smarter than I am, which is a really huge asset. We'll see what he does. The Utah thing, I think, is going to put him in the right position for going forward. Who knows?

My grandparents, how would they deal with seeing all these El Cholos, knowing that their name is on the intersection, knowing that we have two fine dining restaurants in Newport Beach, how would they feel? I hope they will be very proud and feel very good about it. I'm hoping the same thing, that if I came back in 100 years, I would say, "Oh, my gosh. Look how well they've done with them!" Only time will tell.