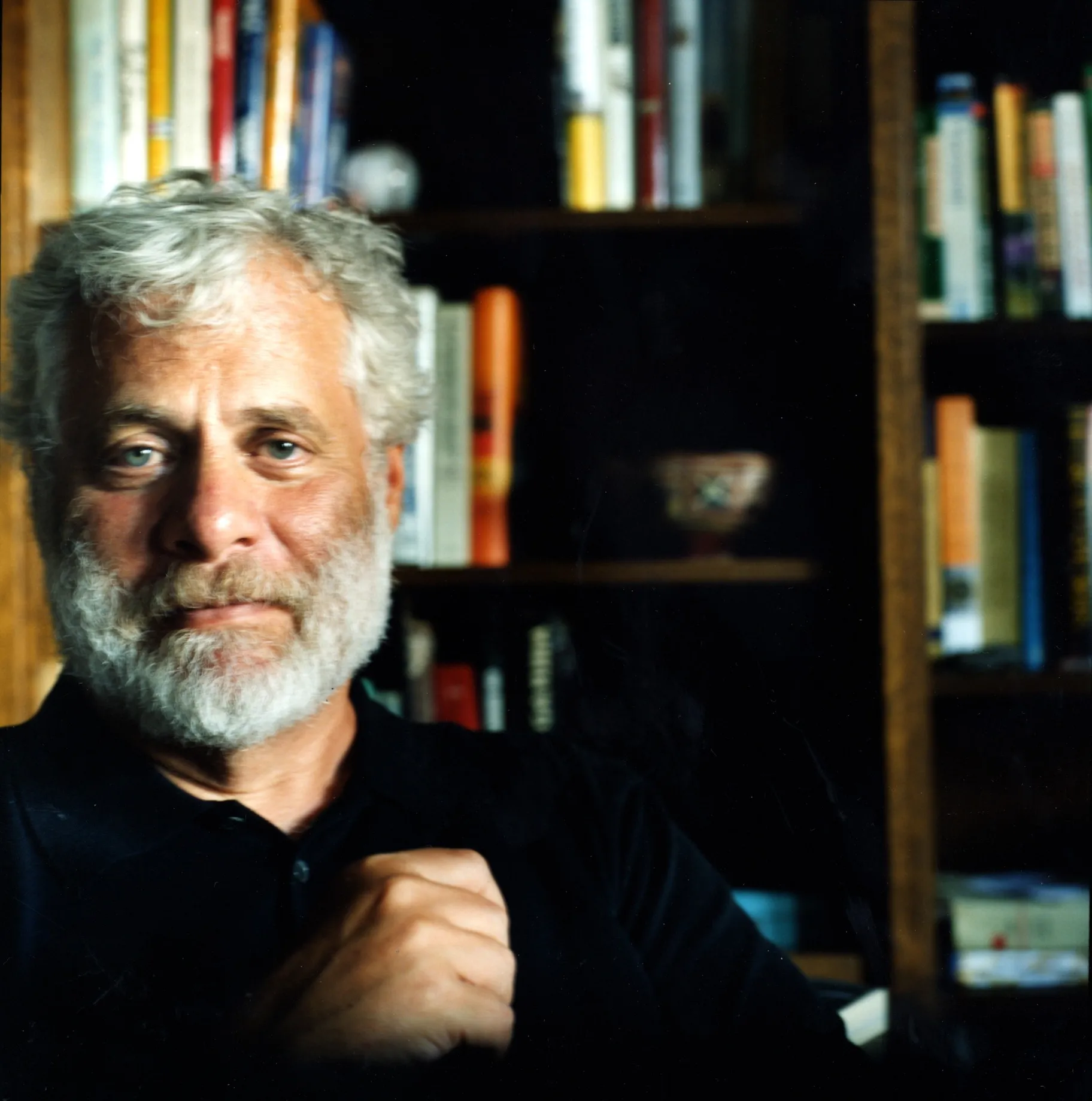

"An onion is similar to a tulip," explains journalist and author Mark Kurlansky. "It's a bulb that produces a flower, each layer is the food for a different shoot." But once the bulb has flowered, it's no longer good to eat.

Onions are hardy, growing everywhere from the desert to the Arctic. It helps that they have a mechanism that was probably designed to protect them from mammals, Kurlansky explains. When you cut into an onion, it releases a gas that gravitates toward our eyes, making us cry. Kurlansky recommends wearing glasses or running a faucet to prevent tears.

Onions have been credited with preventing scurvy and baldness. They were also believed to be an aphrodisiac and authorities sometimes created sexist ordinances to prevent people from being driven mad with lust. In Ridgeland, South Carolina, women weighing under 200 pounds could not be seen eating an onion in a restaurant or at a public picnic if they were wearing shorts.

Kurlanky's latest book is The Core of an Onion: Peeling the Rarest Common Food – Featuring More Than 100 Historical Recipes.

Henri Charpentier was born in Nice in 1880 and went on to cook for and later supervise some of the most famous restaurants in the world, including the Savoy in London and Delmonico’s in New York. In 1948, he opened his own fourteen-seat restaurant in Redondo Beach, south of Los Angeles, where reservations had to be made more than a year in advance. He cooked for the rich and famous, and his most celebrated invention was crêpe suzette, which he made for the British royal family who were dining with someone named Suzette. He also offered traditional Paris-style onion soup, although made with red onions and, to please President Theodore Roosevelt, he made it with Parmesan cheese rather than Gruyère. In his memoir, Those Rich and Great Ones, or Life à la Henri, he wrote at length about his relationship with Roosevelt and about the Teddy onion soup. Henri was also one of the last to write a recipe really well:

Invariably, I think, he wanted onion soup. The first time he came he was dubious because he thought mine would not be so good as some he had eaten in France.

The way to make it, Henri style, is to slice, on the bias, three red onions previously peeled. I put these slices in a casserole containing a tablespoon of hot butter. Into this bland substance the onions surrender all their juice. Properly this should be accomplished over a slow fire. This part of the process is complete when the onion slices have turned the color of gold. Three onions, I find, are sufficient to provide the flavor for soup for two persons; four may make sufficient for four or five, but for myself, when I am hungry, I want six onions. Henri wants his onion soup thick, but even I want them well cooked. The breath of a raw onion is completely uncivilized; but a thoroughly cooked onion, remember, leaves you inoffensive, even desirable.

When your onions have turned the proper color then you add to them about a quart of cold chicken or beef consommé. Now permit this to boil thoroughly; between a half and three quarters of an hour. The final action is to toast a slice or two of bread or a handful of croutons and then in the heat of your oven melt on these grated Parmesan or Swiss cheese. Launch these cheese-laden rafts gently on the boiling hot soup, cover the pot and then place it in the oven for ten minutes. This part of the process gives to the soup the flavor of the cheese. It is, therefore, most important. When you serve send along as an escort a saucer of grated Parmesan for the use of those whose taste is less delicate than yours and mine.

“Henri,” said Mr. Roosevelt many times, “I think I like your onion soup better than that I have eaten in France.”

Well, I myself do not say it is better. I am content to know it is as good.

From The Core of an Onion: Peeling the Rarest Common Food – Featuring More Than 100 Historical Recipes by Mark Kurlansky, published by Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © Mark Kurlansky, 2023. All rights reserved.

Cod, salt, salmon, and milk are a few food items that have spurred Mark Kurlanksy's work. Photo by Sylvia Plachy.

"The Core of the Onion" features historical recipes of a vegetable that has flourished around the world. Photo courtesy of Bloomsbury.