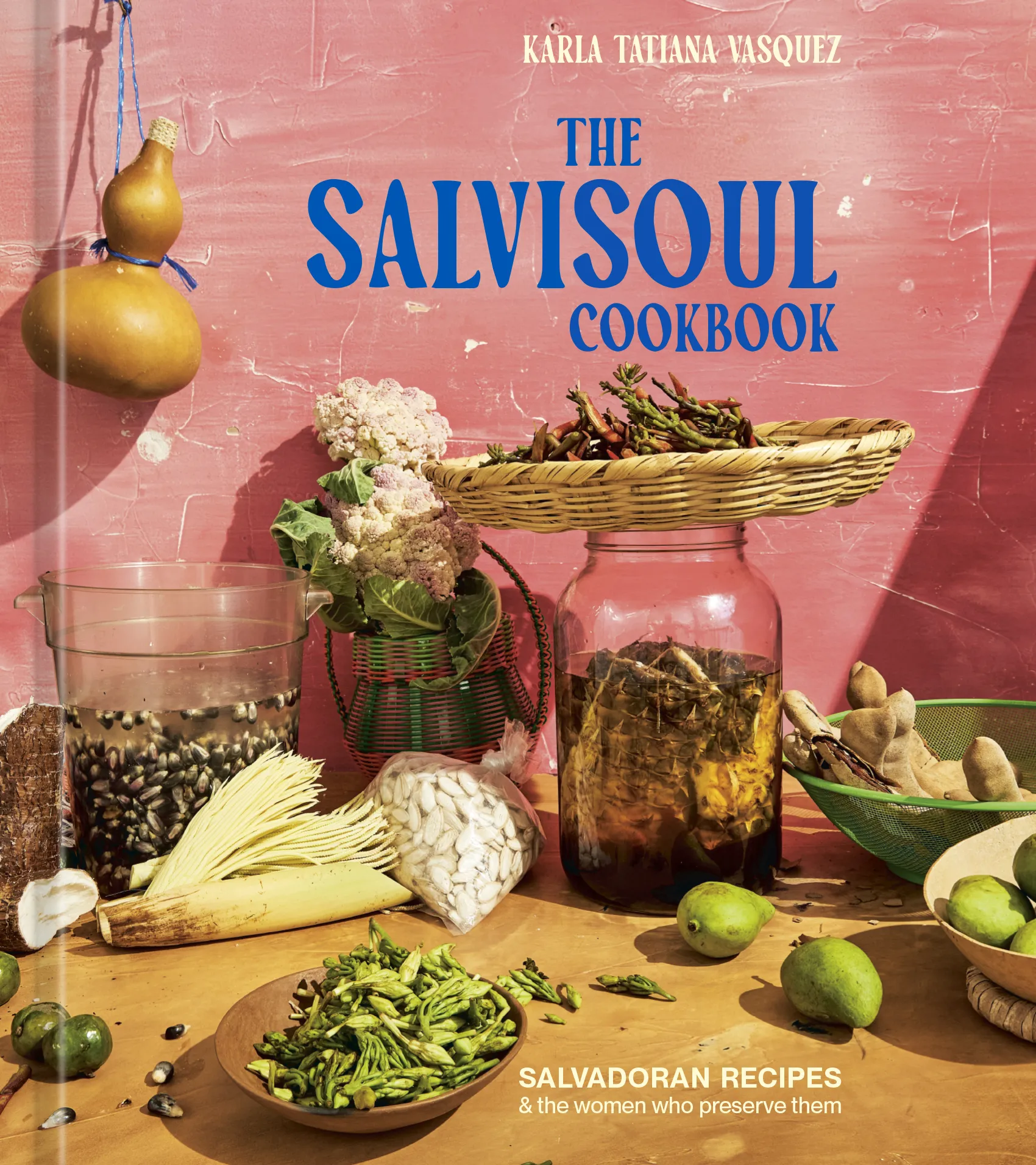

They say you can find anything on the internet. But when Karla Tatiana Vasquez went looking for Salvadoran recipes, she couldn't find many that satisfied her, nor a cookbook in English. So the writer, recipe developer, and food justice advocate decided to seek out and document them. She founded SalviSoul, initially as a way to preserve her family’s recipes. Since then, it has grown into so much more, expanding to document cultural memory and intergenerational connections among the Salvadoran diaspora. As part of that, she has just released The SalviSoul Cookbook: Salvadoran Recipes and the Women Who Preserve Them.

Evan Kleiman: Can you share with us the context in which your family found itself in Los Angeles?

Karla Vasquez: Yeah, my family, like so many other families in the '80s, they had a lot of decision-making to make and weighing choices of whether it was safer to stay during the civil war or whether it would be safer to go on a dangerous track across many countries to safety. So my family left El Salvador in the late '80s and we arrived here in the late '80s. It took about a month for them to leave El Salvador and then find themselves in Los Angeles.

What was the impetus for this book?

Oh, man, there are so many. I think a big one has got to be my grandmother. Growing up, I always felt like there was always this anxiety realizing that my grandmother wouldn't be here forever. I think a lot of immigrant kids feel that way about their grandparents. There's a very special bond and I think it's the yearning for understanding homeland and roots. Somewhere in 2015, I had this craving for salpicón. Salpicón is a wonderful meat dish. It's a dish with beef, served with frijoles licuados, rice, and a nice green salad on the side. I really wanted to make it and I didn't know how. So I reached out to my Mama Lucy and I said, "Ma Lucy, me ayuda, can you help me? And she said, "Claro que si, Karla. Yo te ayudo."

In that first cooking session we had, I got to hear her story. I'd always heard her story from my mom's point of view or other family members where they had this tone of, "Wow, look at all she suffered. Look at all the things that she persevered." It was an outsider's point of view. Listening to her share her own story, she was empowered, she was the heroine of the story. She was sharing with me that these were the choices, the options for a woman in the '60s in El Salvador and she made the best ones that were available to her.

I quickly realized this is so much more. I'm craving more of these stories. I want to know more. I shared with her I said, "Ma Lucy, I have this idea for a project. Maybe I record some more of your stories, like we have been doing, with a few recipes." And she quickly was like, "Karla, claro que si." I said, "Yes?" And she said, "Yeah, de esto se trata de legado de la mujer salvadoreña," which translates to, "This is work about the legacy of Salvadoran women." So my grandmother is definitely where all of this started.

"One of the things that's very popular to eat in El Salvador are blossoms," says Karla Vasquez. This classic dish of flor de izote con huevos is made with yucca flowers. Photo by Ren Fuller.

Now to the food. What are the primary colors, flavor-wise of the Salvadoran kitchen?

The Salvadoran food palate is definitely one that loves salty, funky, tart, acid, fire-grilled foods. There's a huge appreciation for bitter flavors. I know in most cuisines or in modern cooking here, we try to add more fat to disguise the bitter flavor, but I have actually learned a lot about how much we love bitter flavors.

One of the things that's very popular to eat in El Salvador are blossoms. We eat our national flower. There's la flor de pacaya. Obviously, a lot of folks know about la flor de loroco, which is in pupusas. Growing up as a kid, I wanted to be in the flower-eating club but I couldn't get past these bitter notes that are just so present. But they're there and they're celebrated. It's not something that you are disguising with fat or sweetness or salt or acid. You're really just wanting to appreciate it because that's la esencia. That's the essence of it.

Customers shop at La Libertad market in El Salvador. Photo by Ren Fuller.

The flor de izote particularly interests me because I have a huge stand of yucca trees in front of my house. For decades, I've been aware of their use in much of Central American cooking. In fact, every year when they flower, people come and ask my permission to harvest the flowers, which I just think is so wonderful. So tell me, what's the classic dish that they're used for?

The classic dish that they're used for is huevos con flor de izote with some tomato. It's a breakfast dish or sometimes it's actually served for dinner. So after you have your flores de izote and you've cleaned them up, you do a little sofrito of tomato, onion, maybe you throw in a little jalapeno and bell pepper. Then you go ahead and add your flowers after that has softened. You finish with some soft scrambled eggs. You mix it all and now you have a wonderful scramble.

I should also say that there are several different kinds of varieties, similar to how we have different varieties of oranges or tomatoes. There are different yucca flowers. The variety that grows in El Salvador is a little different than the variety that grows here in LA. But it still remains true that they are very similar.

What kind of beans are used in Salvadoran cuisine and how does one pot of them reveal different uses as the week progresses?

Yes, so we love frijoles de seda, also known as Salvadoran frijoles, Salvadoran beans. Seda means silk, so it's a red silk bean. I've made the mistake, when I was early in my cooking journey of thinking, "Oh, it's just a red bean. It's just a red frijol. Any will do." That is definitely not the case.

The frijol de seda is super delicious. I love it. It gives you such a creamy and silky texture once you puree it. Having an olla frijoles can definitely take you many places. You start off on Sunday with your pot of frijoles. You may make that into a soup that has mamasos, which are little corn dumplings of sorts, into your soup. If you have some left over, you may choose to make a casamiento. Or you may choose to blend them and then you can have them with plátanos fritos. Or you can choose to refry them for pupusas. It's one of the things I love. It's so fun.

If you haven't been raised in a Salvadoran or Latinay household, it may seem strange to have a pot of beans... you leave it out, you don't put it in the fridge or anything like that, because it's there, it's easy. You boil it in the morning, you boil it right before you go to sleep. You boil it every time you take from it. It's always food in the house all the time.

For Karla Vasquez, one inspiration for writing a cookbook was her grandmother. Photo by Ren Fuller.

Tell us about relajo. What is it and how is it used?

Relajo is the name of the spice blend that's used for our tamales. In the tamales, there is a sauce and the sauce is called recaudo and the recaudo is made with relajo. Relajo has pumpkin seeds. It has chilies, sesame seeds. Different people will add peanuts. They'll add all kinds of spices, bay leaves. Everyone has their own interpretation.

I think learning about relajo also calmed some of my anxieties about becoming a person who's dedicated to cooking Salvadoran food. I've seen these women who I've learned so much from and felt like, whatever they say is law and you can't steer too far away from it. Then you ask them about their relajo recipes and they'll say, "Well, I would never put this in it" or "I'd never make the mistake of using that kind or this blend" or "The percentage of this seed must be higher than that." You find everyone has a little bit of a difference but, essentially, it's spices and seeds and chilies that are toasted then blended in a sauce with tomatoes, onions, bell peppers, garlic, and that's what's used in that recaldo.

It's an endearing term too, because relajo also means chaos. So it's a cute, endearing thing to say, "Salvadorans love relajo."

Flor de Izote con Huevos

Serves 2 to 4

There is a saying among Salvadorans that despite the hard times that might fall on us, we’ll never go hungry because we eat many things. We are known for consuming the parts of many different types of plants, including buds and flowers. We even eat our national flower, flor de izote, or yuca flower. This white blossom is native to El Salvador and other Central American countries. The petals on the stem face downward, reminding me of the posture of Mother Mary, delicate and precious.

Ingredients

- 5 cups flor de izote (about a flower stem’s worth of petals, or one 32-ounce jar; see Consejo)

- 4 cups boiling water

- 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 medium Roma tomato, diced

- ¼ medium red onion, diced

- ½ medium green bell pepper, cored and diced

- 5 eggs, beaten

- ½ teaspoon kosher salt

Instructions

-

Rinse the flor de izote under running water to flush out any insects that may be hiding among the petals. Place the flores in a large bowl and pour the boiling water over them. Let sit for 10 minutes, then drain and set aside.

-

In a large saucepan over medium heat, warm the olive oil until it shimmers. Add the tomato, onion, bell pepper, and salt and sauté until they cook down and soften, about 4 minutes. Add the flores and cook until everything has combined thoroughly, about 5 minutes more. Turn the heat to low and add the eggs. Using a rubber spatula, thoroughly mix the vegetables, flor, and eggs and cook until the eggs are set, just a few minutes.

-

Serve the flor de izote con huevos immediately.

"The SalviSoul Cookbook" features recipes for mamasos, salpicón, tamales, curtido, olla de frijoles, and many other classic Salvadoran dishes. Photo courtesy of Ten Speed Press.