It's always interesting to learn how place and culture work together to create cuisine. One cuisine that hasn't had a lot of representation in English language cookbooks is Afghan cooking. Zarghuna Adel is making a dent in that issue with her 2023 book, The Best of Afghan Cooking. Filled with personal stories and detailed recipes, it takes us into a kitchen where even the virtual aromas are seductive.

Evan Kleiman: I'm so happy to welcome you to good food. Where in Afghanistan Did you grow up?

Zarghuna Adel: I grew up in Kabul, the capital city. When I graduated from Kabul University, I got a scholarship to study at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon, where I got my master's degree in education. And then the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and I couldn't go back. So I came to the United States and right now I live in Moreno Valley, California.

Were you allowed to help cook when you were a child?

Not really, no. When I was about seven years old, I was always curious to see the inside of the pot and tried to stir it. That wasn't safe. My mom wouldn't like it. I couldn't reach the pot because I was too little. My mom insisted that I could not stir any pot until I was tall enough to be able to see the inside of it. Later on, when I grew tall enough to see the inside of the pot, this was when my passion for cooking ignited because then I could see. I was so delighted. I was so happy.

I love that. In all the years that I've talked to people about their childhood memories and being next to their mom in the kitchen, I have never heard that said, that you have to be tall enough to look inside the pot. But of course it makes perfect sense. So when you finally were able to look into that pot, I imagine that most of your learning was just by standing and watching.

Yeah, that's true. I grew up in a country where you learn cooking through many trials and errors and through eyeballing measurements to evaluate food consistency. So normally a year of practice turned one into a cook, and all married women were considered cooks. In fact, there was no demand for a cookbook. You couldn't find a cookbook there. That's why.

Zarghuna Adel, who grew up in Kabul, recalls not being allowed to help in the kitchen until she was tall enough to look into the pot. Photo courtesy of Zarghuna Adel.

So even after you were older, maybe college age, and you were living in Beirut, you couldn't reference an Afghan cookbook.

No, no. Now there are some but some books are written not by an Afghan. It's written by someone who didn't grow up with the cooking, so I find that when I read it, I see some flaws and differences.

When you were still living at home, what was the dish that you would wait for your mom to make? The dish that you couldn't wait to be served?

My most favorite one was the ashak dumpling. That was because my mom would let me take it apart and [do the] filling, even when I was five or six years old. Then I couldn't seal it properly. I didn't like the looks from them and I didn't like that my work was double-checked by grownups but I still enjoyed eating it.

Can you describe them?

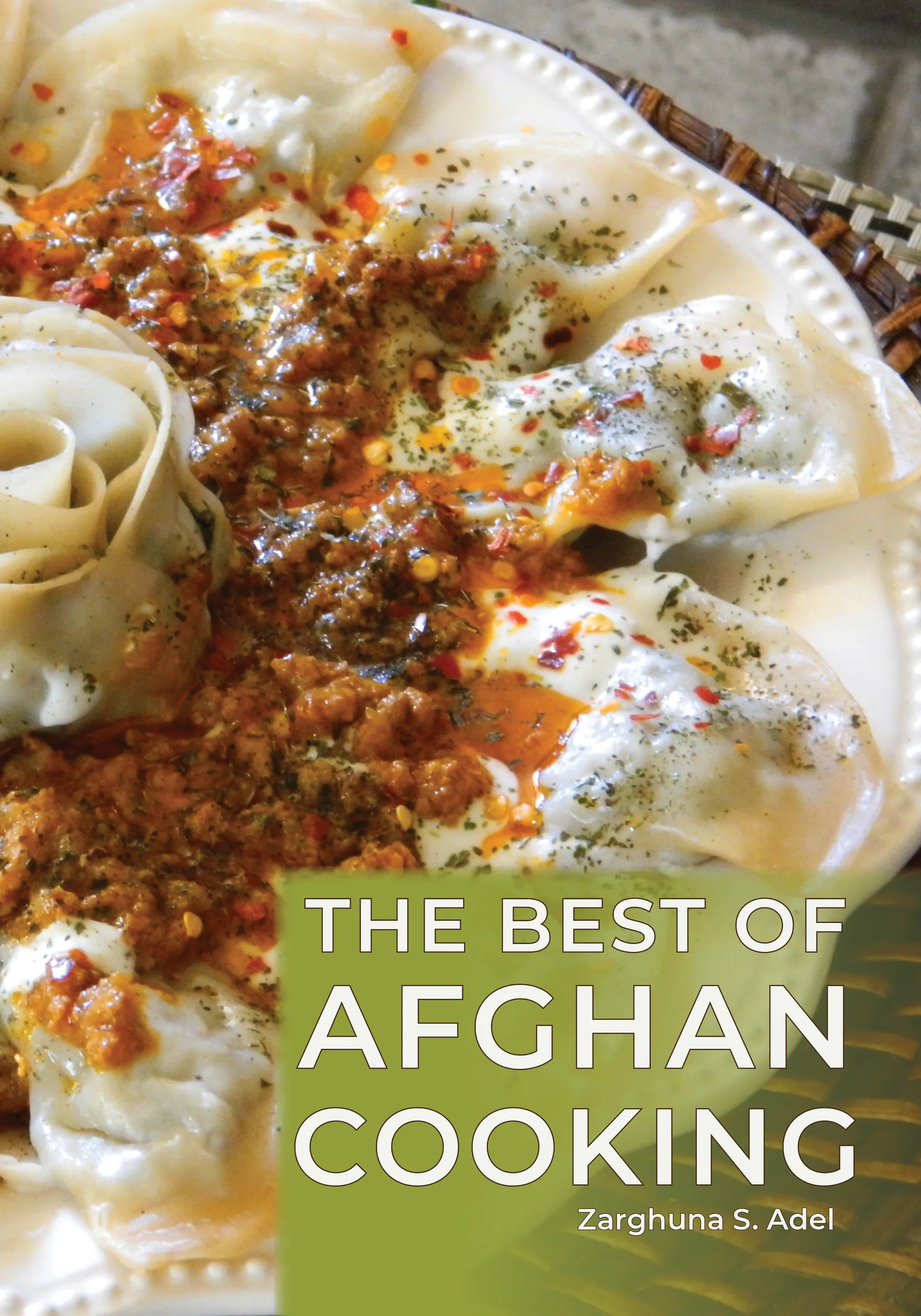

We have leeks in Afghanistan. It's a form of leek called gandana. They're a finer version of what we have in the United States. We cut them really finely and mix them with spices. Then we have those wraps, they're usually round. We fill half of the wrap with the leeks, we fold over the other half, seal it and steam it. Then we prepare a meat sauce that goes on top of it and we make a bit of yogurt before we transfer it to a serving dish. The photo of this dish is on the cover of the book.

It looks so delicious. When you were living on your own, away from home, was there a dish that you would make yourself when you were particularly homesick?

Oh, yes. The dish I missed the most was called shorwa. It's one of the soups that you prepare with meat, beans and vegetables. We first cook the meat, then we cook the vegetables with it. What's interesting about this soup is we cut Arabic bread in pieces and put it in a bowl. We saturate it with the soup and top it with meat and vegetables. That's what I miss the most. It's like the national dish of Afghanistan. It's served to the poor and to the rich, equally. And it's very healthy.

You were gone for a long time. When you were finally able to return to Afghanistan, how many years had passed?

Oh, those were long years. I returned after 25 years.

What did you find, from a food standpoint?

Unfortunately, the authentic food I had been missing for such a long time had vanished and was replaced by unfamiliar foods from neighboring countries. The aromas, flavors and ingredients were totally different. I found out that experienced cooks had either fled the country or had passed away. That was so sad to see that happening. And the younger generation had brought with them the cooking culture of the countries they had been living in. That was so sad, so disappointing for me to see that.

That's what inspired you to create a cookbook to document everything that you had learned and that others were willing to teach you.

Yeah, even before that, in the United States, it was my hobby to cook and to make recipes. But I had so many questions that were left unanswered because I couldn't find those experienced people to ask them. So that was the best chance for me to go there and complete my book. Fortunately, there were some people of the older generation that could help me. That's how I completed my book. I came back with those recipes and I couldn't wait to write the book and finish it.

Tell us about the group that you founded of Dari speakers on social media with whom you first started to share your recipes.

I knew social media was an effective tool to spread the word about authentic recipes and was missing in the country. My project was aiming at two objectives. First, I tried to filter my recipes through an older generation of Afghans who already had the knowledge of old recipes, and who lived abroad. The second purpose was to reintroduce the Afghan recipes to a younger generation living inside the country. And [social media] helped. The group was getting bigger and bigger. The social media comments I had were very effective to ensure the quality of my work.

It was a really big group, over 100,000 people.

120,000 people, mostly Dari-speaking from my country. I first wanted to reintroduce those recipes to them. Then, I translated it into English, and I came up with this book.

Ashak, traditional Afghan dumplings, are common throughout Afghanistan as well as parts of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Photo by Xerxes931/Wikimedia Commons

If readers are already familiar with Persian food, Indian food and Turkish food, can you talk a little bit about what similarities and differences are expressed in Afghan cuisine?

To tell you the truth, I really love Iranian, Indian and Turkish food. I had this food for a long time. In terms of spiciness, Afghan dishes stay somewhere in the middle, between Indian and Iranian and Turkish. In terms of diversity, we have a huge use of rice in our cuisine. We have close to 17 dishes of long grain rice that are prepared with meat, vegetables and fruits. I haven't seen this in other cuisines. With our short grain rice, we have eight recipes and they're prepared with mung beans, and a lot of stews — vegetable stews, fruit, meat and stuff like that.

I cannot compare our rice recipes to the neighboring countries' recipes but the meat, when you say "kabob" to Iranians and Turkish people, kabob is a grilled meat. But our kabob is anything that's grilled, baked, steamed or slow-cooked. They're all called kabobs. We have a huge list of kabobs too but it doesn't mean they're only grilled.

Then, we have the use of yogurt. It can make a very delicious drink that we prepare with dry mint, cucumbers and salt. It comes out very nice. Besides the drink, we can use it as a bed for many dishes, like dumplings and all the borani dishes. Sometimes, we use [yogurt] as a topping for certain dishes, especially fried ones, because it balances.

The very first photo of food in the book is an eggplant tomato borani. Can you describe it and the role of indulgences and appetizers, as you call this chapter, in Afghan hospitality?

In this appetizer, the eggplant goes through three stages of dehydration, frying and steaming, with tomato slices and spices. It comes out creamy and delicious. It's served on a bed of yogurt and we mix the yogurt with some salt and garlic. Like other indulgences, this appetizer symbolizes Afghan hospitality, preparing a special treat for a loved one.

I remember when I would invite my friends home, like my best friend from school, I would think of making one of those. Let's have some borani banjan for her, the eggplant appetizer she really liked. We serve it with Afghan bread on the side. It comes out delicious. Many other dishes like samosas, dumplings, fritters and fried stuff, dough like the bolani [a stuffed flatbread] serve the same purpose.

In the soup chapter, you have this soup that I find so interesting — the spicy sourdough soup. How does sourdough make its way into the soup?

This soup comes from the west of the country, from Herat province. What they do is they make a powder and they save that powder in jars. They can use it several times when they feel like having sourdough soup. But there's another very special ingredient that goes with it, dry meat. Sometimes it's difficult to get dried meat at the market. It's not found so people prepare it at home. We can replace it with lamb pieces.

Before that, we have to make the powder. We prepare a dough with flour, spices, tomato sauce, yogurt, garlic and dry yeast. We leave it at room temperature for about two days. Depending on the room temperature and whether it's summer or winter, it may take longer. Then we shape it into a cake and bake it in the oven. Then it's processed into a fine, bread crumb consistency. We store it into jars for several uses. After the soup is cooked and ready, a certain amount of powder is gradually mixed into the soup. We simmer it for only 10 minutes and the soup is ready.

It sounds so delicious. It must be tangy.

It is a little tangy.

Thank you so much, Zarghuna. I love the book. I probably spent a couple hours with it the first time I opened it because every page was something so different and lovely to learn.

I'm glad you liked it. I hope you try some of the recipes.

Ashak

Leek Dumplings with Ground Beef Sauce

Serves 8

This delicacy, tender leek dumplings with a touch of yogurt served with a ground beef sauce, is prepared in all regions of the country. However, the finest ashak is prepared in Kabul homes. In villages, the dough is shaped into tiny balls and flattened into thin patties for individual ashak. The ground beef and yogurt are fresh and organic. Afghans love to prepare ashak using the teamwork of family members.

Ingredients

For the wraps:

- 4 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon salt

For the filling:

- 1½ pounds gandana, finely chopped and rinsed (leeks, scallions, or Chinese chives can be substituted)

- 2 teaspoons salt

For the beef sauce:

- 4 cups chopped onions

- ¼ cup olive oil

- ¼ cup butter

- 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1½ teaspoons salt

- 2 teaspoons cayenne pepper powder (optional)

- 1 tablespoon ground coriander seeds

- 1 tablespoon tomato paste

- 1½ pounds lean ground beef

For the topping:

- 2 cups chaka (drained yogurt; see page 138)

- 2 teaspoons garlic paste

- Pinch of salt

- ½ teaspoon dry crushed mint

Instructions

-

Mix the flour and salt with 1½ cups water and knead well to form a firm dough. Let the dough rest for 15 minutes. Divide the dough into three balls and cover. Working with one ball, form the ball into a patty and then, using a rolling pin, spread into a thin sheet the thickness of a dumpling wrap. With a cookie cutter cut into 2½-inch rounds and sprinkle with flour. Do the same with the other balls of dough. Set aside four dough circles for the center flower (see below).

-

Sprinkle the gandana with the salt and leave for about 15 minutes. Mix well then squeeze out the extra juices. Set aside.

-

Prepare the dumplings: Dip your finger in water and run around the edge of a dough circle. Then place 1 tablespoon of the prepared filling in the center and fold over the dough to make a half-circle. Seal by pressing the edges together. Sprinkle with flour. Repeat with remaining dough circles.

-

For the decorative center flower: Overlap four dough circles in a straight line, moistening between the overlap areas generously so they can stick together by pressing them down. Place three tablespoons of filling along the top of the circles. Fold the dough circles in half and then starting at one end roll loosely into a flower, leaving the top open. Pinch the end of the roll to seal. Adjust the flower petals by opening them more to a desired shape.

-

Stir-fry onions in the oil and butter until golden. Add turmeric, salt, cayenne pepper powder, coriander seeds, and tomato paste. Stir-fry on medium heat for about 1 minute. Add the ground beef and stir to mix with the sauce on low heat, breaking up meat lumps. Stir in 1½ cups water. Then cover and cook gently for about 20 minutes or until the water has evaporated. Spoon off most of the oil and discard. Keep warm.

- Mix the chaka with the garlic puree and salt and set aside.

-

Cooking Method 1: Boiling. Mix 3 quarts of water with 1 teaspoon salt and bring to a rolling boil. Slide in the dumplings and boil gently for about 10 minutes, pushing the dumplings down into the water with a spatula for even cooking, until translucent and cooked through. Using a large slotted spoon catch a few dumplings at a time, letting the water drip back into the pot. Steam the flower separately using a steamer.

-

Method 2: Steaming. After filling the dumplings, arrange them, including the flower, on a well-greased steamer (mantu) and cook for about 40 minutes or until soft and transparent.

-

To serve: Place the flower in the center of a serving plate. Spread half the chaka mixture onto the serving plate. Transfer the dumplings onto the chaka around the flower. Spoon the remaining chaka over the dumplings. Then pour the beef sauce evenly over the top of the dumplings and sprinkle with the mint.

Few English language cookbooks have focused on Afghan cooking — until now. Photo courtesy of Hippocrene Books.